136: You Are Here

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

Amy McGuiness flies people to the North Pole, tourists who pay thousands of dollars for the privilege. It's a six-hour flight in a prop jet. And for most of that time, if you look out the window, all you see is ice. When you get to the Pole, it looks exactly like all the other ice you've been staring at for hours.

So the tourists climb out of the plane. They're only given half an hour at the Pole. And what do most of them do with the time? Take pictures. And most of them have brought these little global positioning devices, GPSs. And they spend their time looking at the devices which tell them that yes, this is, in fact, the North Pole. Here's Amy McGuiness.

Amy Mcguiness

Getting out of the plane and looking around, there'd be nothing to tell you that you're at the North Pole. They can usually verify it by just powering up the GPS.

Ira Glass

I realize, actually, as we talk, I have no picture in my head of what would be at the North Pole except what you would see in a kid's cartoon, which is a barber pole sticking out of the ground. But there's no such a thing, right?

Amy Mcguiness

No, and it seems ridiculous, and I laugh, but I've had passengers ask, "Where's the barber pole?"

Ira Glass

Oh really?

Amy Mcguiness

Yeah. But we usually, with the groups, we take up some kind of a fake barber pole and stick it in the ice somewhere, just for pictures' sake.

Ira Glass

Oh my.

Amy Mcguiness

Yeah.

Ira Glass

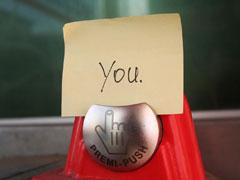

There are the people who always want to know where they are in the world. They move through the world checking their position. And there's a kind of travel that we all do sometimes that's all about that moment of "You are here." You check where you are. You check your position on the map. You take a snapshot. You move on.

The North Pole is just an extreme example. Because, of course, there's nothing there, no one to meet, you're only there for half an hour. It costs $30,000 per person. And, until recently, a regular civilian would have no way to confirm that they were at the North Pole since normal compasses, like the one on the airplane that Amy McGuiness flies--

Amy Mcguiness

Because we're so close to the magnetic North Pole that it basically tips in the jar it's sitting in and is unreliable. It'll be 60 degrees off the proper heading.

Ira Glass

It tips as if to say, "Oh, forget it."

Amy Mcguiness

Yeah, exactly.

Ira Glass

And then there's this sort of person who kind of enjoys the moment when the compass stops working, the moment when there's no way to tell exactly where you are, and no global positioning system to help you figure it out.

Amy Mcguiness

The good and bad thing now that everyone has GPS-- because in a way, it's certainly nice to know where you are. And it takes away a bit of the panic factor. It doesn't matter what part of the world you're in. But there is something lost there in always knowing exactly where you are.

Ira Glass

Well, in a way, it's the opposite of adventure.

Amy Mcguiness

Sure, sure. And adventure, it becomes sort of an art when it comes to finding out or thinking of where you are and where you want to end up.

Ira Glass

On today's radio program, three stories, three people, three sets of maps. And what it's like to be lost, how we all struggle in that moment not to give ourselves over to fear, and, hopefully, try to enjoy it. From WBEZ Chicago and Public Radio International, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass.

Act One of our program today, Ishtar Days, Arabian Nights. A man tries to lose himself completely, leave the places charted on maps. And what happens to you, and what you find when you try to leave the known world like this and succeed.

Act Two, The Game. Writer David Sedaris finds himself in a room full of people in a foreign city. He doesn't speak the language. He doesn't know anyone. And he has one simple, simple mission, a mission that you, yourself, may be capable of.

Act Three, When You Can Snatch The Pebble From My Hand, Grasshopper, Then You Can Leave. One low-paid office worker tries to operate a global positioning apparatus on the map of her entire life. Stay with us, my friend.

Act One: Ishtar Days, Arabian Nights

Ira Glass

Act One, Ishtar Days, Arabian Nights. Back when he was 21, John Bowe decided to visit a friend of his who was in the Peace Corps in Mali, in Africa. But he chose, I have to say, the most difficult possible route to get there. He decided to hitchhike across the Sahara Desert. And not just hitchhike, but hitchhike using a remote route 1,000 miles long that most hitchhikers avoid. He brought no special gear, carried a small bag filled mostly with books, one change of clothes. He wanted to go to places on the map with fewer and fewer roads.

John Bowe

And I don't know. When you travel a lot, when you're traveling and just sort of drifting around, you spend a lot of time looking at the map. And you exoticize it. And you get this weird relationship to it, where you start just thinking, "Well, god, this was cool getting to this remote area. I bet you it would be cooler to get to that area because it's that much more remote." You want to go off the map.

Ira Glass

You want to go off the map? You want to go off the map, meaning you want to go off the area where the roads are on the map?

John Bowe

Right. But you want to go off the map in a more metaphorical sense, too. You want to get off of the grid of American life, the grid of the modern world. You want to get totally away from white people and American techno living that's defined world culture.

Ira Glass

How easy or how hard was it to get off the map?

John Bowe

Well, that's one of the really interesting things. You can hop on a plane from anywhere to anywhere, hop on another little plane or train or something else, and then walk 20 feet and be in the middle of nowhere, which is one of the weirdest things about the modern world. You could take a plane probably from New York to Manaus in Brazil, and take a boat, and immediately be lost in the middle of the rainforest. And it would take you all of a day to get there.

So the idea was to hitchhike across the Sahara Desert. And at first, I had had this idea because of my trusty Michelin map. They indicated that there was still a camel caravan that goes back and forth between southern Morocco and Timbuktu. And I kept asking people around, "Is there still a camel caravan that does this thing?" And people were kind of saying, yes, but only the people who were trying to sell me stuff, like, "Yeah, well, but you're going to need a lot of stuff for the journey. Why don't you buy this $300 worth of stuff?" So it's like, "Well, let me just make sure there's a caravan first."

And then it's funny because, later, I found out about some German kid who had actually bought $1,000 worth of gear. And they said, "Oh yeah, just be here." They sold him a camel.

Ira Glass

And just wait here.

John Bowe

Right. Be here on the second Sunday of every month, and the guys all come. You can start your journey then. So that seemed like it wasn't going to happen.

So then I went to Algeria, down to Tamanrasset, which is about a third of the way across the desert. And then the plan was to hitchhike from there for the rest of the way. And it's weird flying over the desert because, at least this day, there were no clouds. You just see what it is you're getting into.

It's just sand. And maybe 30 miles over to the right of the plane, there might be a little oasis with just this little cluster of trees around it. And maybe 50 miles over to the left, there might be another one. But on the ground, that's 80 miles step by step in this 130 degree environment.

Ira Glass

So it's frightening.

John Bowe

It's completely frightening. At that point, when you're still in the safety of an airplane, you're still on the map. You're still on the grid. But you definitely got the sense of the place that this is sort of the last stop on the grid.

So I get to the outskirts of town. And of course, on the Michelin map--

Ira Glass

Now you're looking at the map.

John Bowe

I'm foraging. OK, here we go. Now the way the Michelin map marks roads is sort of arbitrary. In fact, you might even say capricious if your life depended on it, which, pretty soon, mine was going to. Because they make these things look like roads. But you don't realize until you get there, all they are are tracks in the sand.

Ira Glass

Will the sand just blow over them, and then there's just nothing?

John Bowe

Right. And there are dust storms frequently in this area. Tamanrasset is located in this place called the Hoggar, which they filmed a lot of commercials there. Whenever they're doing those commercials where someone says, "We went to the harshest environment on Earth to test--" whatever, DieHard batteries or whatever, that's where they go.

So anyway, so I got to the outer part of town. And I'm looking for what appears on the map to be a road. I've got my Michelin map, and I've got this faulty compass that it just would spin around and never be consistent.

Ira Glass

Really?

John Bowe

Yeah, it was a really bad thing in a compass, right?

Ira Glass

Describe the compass, please.

John Bowe

I can't remember much about it. It was a little cheap, $2 or $3 compass. This was the whole problem with the trip in so many ways is I just deliberately outfitted myself as poorly as possible.

Ira Glass

Anyway, so you're there.

John Bowe

OK. So I'm there, and my compass is spinning around, not even wildly. It's just lazily spinning around. And I couldn't find any paved road. There were just these tire tracks radiating out in all directions from the town. There's no sense. There's no such thing as signs, saying, Denver, this way, Amarillo, that way.

I don't stop for a minute to think, "Well, this is kind of stupid." I have a liter of water, no provisions of any kind, and I'm talking about heading across 1,000 miles of desert. It just didn't enter my head the degree of stupidity of what I was doing.

Ira Glass

What was in your head? What were you thinking?

John Bowe

You think you're being plucky rather than stupid. You're just looking at the goal of trying to get lost. Well, this is cool, but there's a city here. And you can always go further and further off the map. Oh, I bet you no one's ever done this.

And in fact, there's something prideful about this is so stupid that no one else would dare to do this. You know what I mean? I bet you no one else has ever set off to cover 1,000 miles of desert with a quart of water in their pocket.

So I start walking. And again, it's 120 degrees, 125. It's heat waves everywhere. And you start walking down the road. And after a mile or two, a truck came along. So I hop in with this guy who turned out to be named Kurumi.

And we're cruising along. It's so incredibly desolate. Every once in a while, a lizard would scurry across the road. But you got the sense that if you were out here in this heat, lost, you would be gone in a second.

On my route, in the end, I found out stuff like if your car broke down from the heat, you were dead. You were just dead. Because there were so many days in a row when cars didn't go by at all. And the nomads would eventually come and pick your car clean. And you'd just be screwed.

So I woke up in the morning, and we drove the rest of the way and got to this town, Timiawin, in the afternoon. And I walked over to what was the border post. And it was just the only place in town with a flag flying over it. And there was this guy who seemed to be the head official who was just loafing around on a mattress, on a bed stand, in the street, outside the border post, just sitting around in the shadows, picking his nails.

And I said, "Hi." I'm all bright and shiny still, like, "Hi, can I get my passport stamped?" And he said, "Well, why don't you sit down?" So I said, "OK." So he was just sort of-- he was talking.

And finally, after a while, I said, "So do you think you could stamp my passport?" Or no, he said, actually, "OK, well, I'm ready to stamp your passport now. Will you hand it to me." And I looked around, and I looked around, and I couldn't find it. And I said, "Well, I think I must have given it to you, right? Didn't I give it to you before?" And he said, "Yeah, but I gave it back to you."

And I looked through my stuff again. And I said, "No, it must be somewhere. I think you have it because I don't have it." And he said, "Well, you better check again because if you don't find the damn thing, I can't stamp it, and you're going to be stuck here in Timiawin. And so I check one more time. And I'm getting completely sweaty.

And then he just starts smiling, and he lifts his leg. And it's been hiding under his leg the whole time. And he goes, "Ah, got you." That's your usual border post official behavior.

Ira Glass

It's so interesting that if you are a border guard, there's one joke that you can enact on every customer. And that is the ancient joke. That joke dates back centuries. As long as there were people and borders, there could be that joke.

John Bowe

It's been passed down from a long line of prankster border guards. So he tells the joke, and then he says, "Ha, ha, ha." And we're good friends by then. And this Peugeot pickup truck arrives at the border post. And it's these Tuareg nomads, maybe six, seven, eight of them.

Ira Glass

Now explain a little bit about the Tuareg nomads.

John Bowe

OK, the Tuareg are really, really, really interesting. They call them "l'homme bleu" in French, which means "the blue men." And that's because they have these veils dyed of indigo. And the indigo gets into the pores of their skin. So even when they take off their veils, their skin has this purple tone. Some of the women tattoo their gums with some indigo thing, so that they have these weird purple gums. It's actually really cool looking.

Ira Glass

And they've been in the desert for centuries.

John Bowe

Yeah, they were controlling the whole salt trade back during the Medieval ages when Europe was getting their salt from Africa and stuff like that. And they made a hell of a lot of money. They lived very well. And they have this very regal bearing. They used to have their very own slave tribe called the Bella.

And my friend, the friendly border post guy, started mumbling to them and pointing over to me. And then he came over to me, and he said, "Oh good, they're going to take you. I did you a favor. Get in the car." And so before I knew it, I was bounding out of town in the back of this pickup truck. Some of them were sitting in the back of it. They had a few big bags of figs or something back there.

So we go taking off. And after about 10 or 15 minutes, they stop the truck. And they whip out these mats, and they face Mecca, and they start praying. So you hang back and shut up. And then they finished up after a few minutes.

Then they piled back into the truck. And they realize, oh yeah, the truck doesn't start. We need to push truck to start. So they said, "Oh, will you help?" And I helped. So we push start the truck, and we get going again.

And then after another few minutes, they stopped the truck again. And I'm thinking, "I really wish that we would just haul ass and get to the next place." And they stop the truck, and they explain to me, "Oh yeah, this truck isn't so good." I'm like, "Oh, OK, well, that's no problem. It's just the Sahara Desert. It's no big deal."

So they get out their tools to fix the truck. And what they have is a beaten-up screwdriver and pliers. And they get under the truck, and I can hear this smashing around and grunting and swearing. At one point, they asked me to come down and help look underneath the car to see if I can help fix it. So I get underneath the car with them. And I realize that they don't have any more idea than I do what they're doing. They're just taking this screwdriver and this rusty, old pliers and fussing around with stuff.

So it started dawning on me, wow, this is a really bad place to be haphazard about this kind of stuff. And I didn't want to be a pain in the ass and start saying to them, "Gee, guys, this is scary." Here it is, it's about 170,000 degrees. And are you worried? That's what makes them be them. They don't worry.

And so you're kind of boiling over inside, but you don't want to be a baby about it. And I also just thought, it's not their business to look after me. Meanwhile, I'm trying like hell. I want to guzzle my water. I want to have a sip of water every minute. But I'm already 2/3 of the way through my water. So I have 1/3 of a liter left.

So we start up the truck again. And we go. And this is going on just for hours now. It gets into the afternoon. Again, this whole routine continues of just stopping the car every few minutes. We stop to pray, stop to fix the car, and I'm starting to go crazy. And I realize it really doesn't take long to go from a stressful situation to outright insanity. It only takes a little while. Because I start running out of water.

Oh, OK, I also should mention they had a baby with them. And the baby that they have is just sitting there, getting more and more and more sickly. And I start just focusing on this baby, as I'm watching it die. It looks like, for sure, this baby's within a day or two of death. And the baby is all wrapped up, so it can't move its hands or feet.

And its poor face is just sitting there, sticking out its mom's back, looking at me. And its eyes are getting all crusty with all this goo. And all these flies are coming around and circling around its eyes, sucking at the goo. And these flies are just sucking and sucking. You just realize any available moisture in this environment gets sucked out.

And that's what the nature of a desert is. And it just starts making you think any tenderness just gets sucked out. And you just start getting completely crazy, just thinking, that's what life is all about.

So one time we stop, and we're sitting there for half an hour fussing around. And these other nomads arrive seemingly out of nowhere on camel-back. And they say, "Hey guys, are you in trouble? Because for some money, we could probably help you out." And our guys yelled at them. And you could tell they were swearing, and they were getting into a fight.

And then the new nomads, the new arrivals came up to me and said, "These guys look like losers. Where are you going?" I said, "Oh, I'm going to Aguel'hoc." And they said, "Well, for--" I don't know how many dollars, I think it was like $70-- "we'll give you a ride there."

I guess I was tied-- I wanted to get the hell out of there and maybe live, for example. But I also felt tied to these guys, and I didn't want to ditch out on them. So I said, "No, no, thanks." And they said, "Well, OK, good luck." And they rode off, and I was just killing myself for not-- I just thought, "Oh god, you really should have gone with these guys because these Beverly Hillbillies Tuareg that you're with are really not happening."

So we just keep having these breakdowns literally every 10 minutes. They say, "Well, I think we better just put up for the night here." So we break camp. And they whip all this stuff out of the back of the truck. And they have all these blankets. And they make a fire.

Ira Glass

And how are you feeling at this point? Because, after all, at this point, you have gotten your wish. You're off the grid. You're off of every kind of grid. You have left the map completely.

John Bowe

Right. It all came to a head right in this night. Because they all go to bed. And they're clustered up in this big ball together. And I'm all alone out there.

And the second they're asleep and I'm all alone-- as I just sat there staring at the fire, and the wind is picking up and making all this noise. And you're incredibly lonely and incredibly alone, wandering around there, picking up the stuff, I realize there is not a sentient being, if you exclude these people who are asleep a few hundred yards over there, there is not a sentient being for hundreds of miles probably. I am the only one wandering around here. And it's just incredibly lonely.

And that's around the time I heard this click. I don't know how well I can put this. It was just finally, I all of a sudden got the sense of yeah, you are really off the map. You are so far off the map. You've never been this far off the map.

And I started imagining, for example, what would happen if you died out here? You would just be gone forever. You would be swallowed up. There'd be no memory, no record whatsoever of whatever had happened to you. No one who ever knew you would be able to find you. You wanted to lose control, and now you've lost control.

But you just catch this little click that the whole universe makes. It's this silent, little chick that says, "Oh, you've passed the point of no return." There are no words you could use to describe what that feeling is like of, oh, I'm so naive, oh, the world is so cruel, oh my god, this is what you wanted, this is what you've got.

Ira Glass

Oh, I could die here.

John Bowe

I could die here.

Ira Glass

I could die today, now. It could happen right now.

John Bowe

And so it's just that feeling of you played yourself. You did it. You kept going further and further out on a limb, and now it just broke. And you're like Wile E. Coyote. You're above the two-mile-deep chasm, just waiting to fall.

I don't know. I think there just was this very arrogant taunt of saying, "Well, dear world, you have to kill me or tell me what's interesting about you." Or something.

Ira Glass

Yeah, give me something to believe in, or kill me.

John Bowe

Right. Dear God, give me what I want, or I'm going to go shop elsewhere. And you don't do that. That's really arrogant. You don't demand answers like that and just get them. And I think the answer that I got was, "No, thanks. We're just going to make you profoundly unpleasant. I'm just going to scare the hell out of you, and then we'll let you live."

Ira Glass

John Bowe is now a writer in New York. After a day with the Tuareg nomads, a truck came by, which put him in motion toward Mali and, much later, towards home.

[MUSIC - "LET'S GET LOST" BY CHET BAKER]

Coming up, David Sedaris plays a game pretending he's lost, plays it over and over, plays, and plays, and plays. Until one day, he experiences the real thing and does not much like it. That's in a minute from Public Radio International when our program continues.

Act Two: The Game

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose a theme, invite a variety of people to bring you stories on that theme. Today's program, You Are Here, stories of people getting lost and how people react to getting lost. Some people seek it. Some people are scared by it. We've arrived at Act Two of our program. Act Two, The Game.

Yes, it can be frightening to get lost. But what if you could adapt the thrill of getting lost, the pleasure of getting lost to safe parameters? Confine it, just get a little, tiny bit lost? Is that even possible? Or is that playing with fire, and you're sure to get burned? Well, writer David Sedaris has made the attempt himself. And so, of course, you don't have to.

David Sedaris

Whenever I find myself in a strange or unusual situation, I like to play this little game. To begin with, I have to pretend that a part of my brain has been asleep for exactly one year, while the rest of my body has been answering the phone and carrying on as usual. Now I've suddenly woken up, and I can't leave this spot until I gathered clues and figured out exactly where I am. The game is generally played during those moments when people tend to pinch themselves as a reminder of the dramatic turn their life has taken.

An example from a trip given as a reward for my college graduation. I'm standing in a grim cinder block building, looking out over rows of porcelain toilets arranged across the concrete floor much like the seats in a movie theater. Men are sitting on these toilets, some of them talking or reading the newspaper and others just staring ahead. There's a 1/2 inch of water on the floor, and a bottle cap floats by followed by a plastic spoon.

I probably came in to use the urinal, but rather than get my shoes wet, I'm deciding that maybe I'll just hold it and try someplace else. I turn to leave, but I can't. The game has begun. And now, according to the rules, I'll have to stay in this bathroom until I either hear or read the name of this particular town.

At this point, the exercise becomes more of an obsession than a game. It's not particularly fun to stand on your toes in an unventilated public toilet. But I'm powerless to leave until the person I was one year ago has figured out where he is. "OK," I think, "let's break this down."

The people in the bathroom are speaking Spanish. They appear to be Mexican, but that's not good enough. They could be-- I don't know-- on vacation or something. In the far corner of the room, a teenage boy is playing a radio, and that's probably my best bet. I'm hoping that sooner or later the announcer might mention the call letters, adding that his is the number one station in wherever it is I happen to be.

Unfortunately, the radio is currently broadcasting what appears to be the Spanish equivalent of "American Pie." I'm waiting and waiting for the song to end when a man enters the bathroom carrying a shopping bag. I read the name of the store followed by the words "Mexico City." And only then am I free to rush outdoors, where my traveling companion says, "Jesus, what took you so long?"

I take pleasure in the game partly because my life so rarely takes a dramatic turn. To put it mildly, I am a reluctant traveler, my preferred phrase being, "You go ahead. Someone needs to stay behind and take care of the cat." My hatred of travel is partially what makes the game so rewarding. I like the dreamlike quality of waking up in a strange place and the clinical way in which I'm forced to view my surroundings.

The game is never arranged in advance. It just kicks in on its own, usually prompted by a combination of visual elements I can only define as astonishing. When played in pleasant circumstances, the effect is narcotic.

Another example. I come to, and I find myself sitting in a cafe, admiring a corkscrew made out of a deer's foot. Something suggests that it probably belongs to me. I've always loved functional taxidermy, as it downplays the sportier aspects of hunting and makes shooting animals seem comically practical. I imagine someone rising at dawn and buttoning up his camouflaged vest. His corkscrew has broken, so now he'll have to go out and kill a deer.

The object sits before me on a table alongside a shaver made from an antler. A waitress appears, saying, "You must have been over to Terry's place down by the river. Oh, he makes such lovely things." The woman speaks English in an accent I can't quite identify except to say that she probably recognizes the authority of a queen. She sets down the cup of tea I had apparently ordered, and I thank her.

At the next table, an infant is crying, and I watch as a young mother fills the baby's bottle with Coca-Cola. In looking from one person to the next, I realize that I have the best teeth in the room. I have never in my life been in such a situation, and I proceed to take full advantage of it. I'm grinning like an idiot when my boyfriend, Hugh, enters the room and takes a seat beside me.

He's not in on the game. But even if he were, it wouldn't do me any good. It's against the rules to ask anyone where I am or to lead the conversation in that general direction.

It's times like this when I notice the difference between the way people talk in real life and the way they speak in the sorts of movies that heap on the exposition in order to cut to the chase. The movie version-- "Christ, BW, we've been waiting on the corner of 8th Avenue and 51st Street in the Hell's Kitchen section of New York City for over an hour and 45 minutes." Real-life version-- "I'm tired."

Hugh mentions a pair of taxidermied owls he's seen in a little shop down the street. This eliminates any doubt that we might possibly be in the United States, a country which forbids the mounting of its owls regardless of the circumstances. Even if one drops dead of a heart attack, you're not allowed to stuff it with straw or turn it into something useful like a desk clock. "You can buy owls here in Scotland," he says. "The only problem would be getting it back home." He lifts his tea cup, adding, "Is there something wrong with your mouth?"

My smile fades. He said the magic word, "Scotland," though I wish he hadn't because now the game is half over. I'm enjoying this little cafe with its views of the darkening street. And although Hugh's presence has ended my brief reign as holder of the room's finest teeth, I want to take my time and play at a leisurely pace.

We sit for a few minutes before the waitress swoops in and formally ends the game. "So," she says, "are you enjoying yourself here in Pitlochry?" It's a conspiracy. She and Hugh get to talking and within two minutes, she's mentioned the street, the country, everything, but the compass points. Check, please.

I've played the game since my first trip to summer camp. And in all that time, I never acknowledged its inherent safety net. While the David I pretended to be was shocked to find himself in Rome, Valencia, or Gastonia, the David I was at the time knew very well that he was in Italy, or Spain, or spending two weeks at Camp Cheerio. It's basically just a simulation exercise like one of those emergency procedure drills enacted by astronauts in training. I never realized what a joke it was until recently, when I found myself playing the game for real, and I panicked. It went like this.

I'm in a grocery store, but aside from the plastic wrapped meats and vegetables, I'm not finding much that I can hold onto. It isn't that they're selling anything remarkably exotic. It's just that I can't read the labels. Here, each word includes no less than 15 letters. And every box and can seems to picture a strapping family unit, smiling broadly for no apparent reason.

It's 6 o'clock in the evening, and the store is crowded with well-dressed professionals on their way home from work. I'm standing in what smells to be the soap and shampoo section when a young woman approaches, pushing her shopping cart with her chin. Her shiny, chestnut-colored hair hangs in front of her face until she flicks her head, and the hair resettles about her shoulders. The woman wears a knee-length skirt and a knit, sleeveless blouse and has no arms whatsoever. She stands beside me, and then she slips off one of her loafers and reaches for a plastic bottle with her bare foot.

There is no awkwardness to this moment. Her leg moves gracefully, and her foot works no differently than a hand. It's even decorated like a hand. Her nails are painted, and there's a gold bracelet around her ankle. And she's wearing a wedding band on one of her toes.

I'm curious as to how she might pay for her groceries, but we get separated at the registers. I realize then that the more important question is how I will pay for my groceries. I understand neither the currency nor the language, so my best bet will be to hand the cashier the largest bill I've got and hope that's enough to cover it. There are only a few items in my basket, a tube of what is hopefully toothpaste, but possibly a vaginal lubricant, a cigarette lighter in the shape of a genie, and five tins of cat food.

I've emptied my items onto the belt when I notice that everyone around me is caring an empty canvas sack in which to pack their groceries. I, myself, have no sack. The cashier offers me no plastic bag. And so after paying with my large bill, I stuff the lighter, cat food, and toothpaste into my pockets, pretending that this is the way I prefer to carry my groceries home from the store.

It's difficult to walk properly with both my front and back pockets stuffed tight with cat food. I'm ready to return to my hotel, but then I notice the armless woman walk out with a bag held between her teeth. And then the game begins in earnest.

I'm looking up and down the busy street, hoping to read the name of this city on a shop window, when I suddenly realize, I have absolutely no idea where I am. I'd recognize the name if I saw it written down. But other than that, I haven't got a clue. My first instinct is to throw up my hands and scream like a girl. And it is only with great effort that I manage to silence myself.

I know for a fact that I am in Germany, but I honestly can't remember where in Germany. I'm here on a promotional tour, eight cities over the course of a week. Monday was Berlin. Tuesday was Stuttgart, followed by Mannheim. But where am I today?

It's a half-hour walk back to my hotel, but that doesn't worry me. I can locate the hotel. I just can't locate myself. Neither can I leave this block and return to the hotel before the game is finished. And this presents a problem as my hosts will be picking me up in a little less than an hour.

Yes, it's just a game. And yes, it's just a rule. But if, like me, you're just a compulsive maniac, you know that games and rules are everything.

I'm thinking I might return to the grocery store and see if they've got a magazine rack. But no, I can't walk in because my pockets are full of cat food, and they might very reasonably mistake me for a shoplifter. A shoe store, a bakery, a record shop. One stand selling flowers and another selling sausages. Through their windows, I see nothing that can help me. I tell myself that sooner or later, a bus will come along, bearing the city's name in bright, easy-to-read letters. 20 minutes pass before I'm able to narrow things down a bit and deduce that wherever I am, it is definitely not on a bus route.

I'm racing up and down the block, desperate for evidence, when I suddenly start thinking about Hugh Downs. I'd seen him once when we shared a flight from Phoenix to New York. He moved through the airport minding his own business, and I'd followed along behind him, watching as people rushed forward to say, "Hey, you're Hugh Downs. What are you doing in Phoenix, Arizona?" He did nothing to provoke this response and was courteous even when the goons at the x-ray scanner stopped him for an autograph, saying, "Well, if it isn't Hugh Downs, host of 20/20. What are you doing here in Phoenix?"

For him, the game would be a snap. Should he develop Alzheimer's disease, all he'd have to do is walk out the door and willing strangers would tell him everything he needed to know. "You used to host The Today Show." "You're Hugh Downs. What are you doing here in--" fill in the blank. Due to his television celebrity, he benefits from what I now refer to as The Downs Syndrome.

The man couldn't get lost if his life depended on it. In my mind, it was now me against him. And he had it easy. This sense of competition spurred me on, and, within minutes, I was rifling through the corner trash can, cursing Hugh Downs' name with every used Kleenex and disposable diaper.

Eventually, amidst the crumpled flyers and crushed paper cups, I came across a discarded ATM receipt. And there it was. There I was, safe and victorious. I retracted all the mean things I'd thought about Hugh Downs, took a moment to gloat, and then, arm in arm with the person I used to be, I walked back to my hotel room in the German city of Cologne.

Ira Glass

Writer David Sedaris.

[MUSIC - "FLY INTO MYSTERY" BY JONATHAN RICHMAN AND THE MODERN LOVERS]

Act Three: Snatch The Pebble From My Hand, Grasshopper, And Then You Can Leave

Ira Glass

Act Three, Snatch The Pebble From My Hand, Grasshopper, And Then You Can Leave. There's a class of people in certain professional fields called assistant. I had a friend who was the assistant for NPR's Daniel Schorr, then the assistant for NPR's Nina Totenberg, then for a New Yorker magazine writer, then for a New Yorker editor. And in all of those years, as this went by, as she watched her 20s ebb away, it seemed impossible to her to ever break the yoke of assistant-hood. The skills to do the job of assistant-- answering phones, faxing beautifully, were entirely different than the skills needed for the jobs that all assistants really want, that is, those of the people that they assist. It's a trap.

Nicole Graev is an assistant to an editor at a publishing house at Simon & Schuster. She finds herself lacking a map to her own life because of her very assistant-hood. She needs a map to where she's going. She's lost. She does not know where she is, and she is not happy about all this. And she set out to find some map to give her a sense, a sense of "You are here."

Nicole Graev

When I was in school, I majored in what is arguably the least useful subject in the English-speaking world, English. And yet, I always saw my future as this vast, sunny stretch of infinite possibilities. And the night before I started my first job as an editorial assistant at Simon & Schuster, I couldn't fall asleep. In just hours, I'd be hitting it, that glorious horizon I'd been speeding towards my entire life.

The thing about the wide and limitless future that no one warns you about, once you get there, it ceases to be wide and limitless. The millions of possibilities suddenly crystallize into one choice, one present, one single five-by-five cubicle. With one swift move, I'd narrowed a world of options down to four foam-core walls and a file cabinet, though I often get to leave to visit the photocopier.

In school it's always clear how to succeed. As long as you work hard, get good grades, you move ahead. But in this job, I felt like I'd hit a dead end. The gap between assistants and editors seemed unbridgeable. We never saw them cut deals, never watched them make decisions, never heard them talking to their authors. On my one-year anniversary at Simon & Schuster, I received a commemorative pen which I used the next day to clear a paper jam.

I decided to track down some of the people who'd started off right where I am now, in the same job, the same company, same building, same floor, to see if anything became of them, if this job actually leads anywhere. They could show me where I was headed and give me the map I wanted to get myself there. I began just 20 steps from my own desk. Michael Korda, Simon & Schuster's editor-in-chief, started here as an editorial assistant in 1958, just 41 short years ago.

Michael Korda

Well, I'm not sure that I'm the very best example of what you're talking about. I came into book publishing without any particular impulse to be in book publishing. I'd fought in the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, having left Oxford to do so.

Nicole Graev

Michael went on to list the multitude of ways in which I'm nothing like him. His father won Academy Awards. His mother and aunt were famous actresses in Europe. His uncle directed his first feature film at the age of 20. At 20, my dad was pumping gas on the outskirts of Syracuse.

Michael Korda

Fortunately for me, there were a number of things that were in my favor. I am a stupendously fast reader and always have been. I can read in at least three languages fluently and two languages with a little bit more difficulty.

Nicole Graev

Where exactly did foreign languages fit into my position anyway? As Michael talked more about his time as an assistant, it dawned on me. His job hadn't been the same one as mine at all. He was an assistant back in the days when American companies still had a job called "secretary." Now in publishing, as in so many businesses, there aren't many secretaries. Instead, they hire college grads like me, pay us less money, wave vague promises in front of us, and trick us by calling us assistants, a misleading title that makes it seem like we're actually on the map, heading somewhere.

I pressed Michael for advice, and he gave me a few of the usual suggestions. Work hard, read a lot, maintain a sense of purpose. "But the most important thing I could do as an assistant," he told me, "was to find some way to make myself stand out."

Michael Korda

In my experience, with very few exceptions-- I am, as it happens, one of the exceptions-- the one thing that most editors don't want to do is edit. It's not nearly as conducive to a successful career as having lunch out with important agents or going to meetings where you get noticed. So my guess is that almost any editor would just as soon leave the editing to somebody else if he or she were certain that the editing would be done in a way not to cause problems. That, to me, is the way ahead for any editorial assistant.

Nicole Graev

I took his advice and dropped in on my boss, Geoff Kloske, while he was editing a manuscript.

Nicole Graev

Hey.

Geoff Kloske

Hey.

Nicole Graev

How's it going? It looks like there's a lot there, huh?

Geoff Kloske

Yeah.

Nicole Graev

If you want, I can take that over later. I mean, if you want to get out of here at some point, I can stay late and-- I don't know-- do a few pages, edit a few pages. If that's-- I mean--

Geoff Kloske

Huh? I'm not going anywhere.

Nicole Graev

Oh. OK, well, if you change your mind--

Geoff Kloske

Yeah.

Jenny Blum

Well, it was a surprise to me how much secretarial things I was doing-- typing, and fetching and carrying.

Nicole Graev

From 1984 to 1988, Jenny Blum worked as the assistant to an editor who sits just two offices down from me. I thought her experience would be closer to mine. And it was. Like me, she'd lived in a small Manhattan apartment that she shared with roaches. She'd answered someone else's phone. She knew what a fax machine was. But then her life turned around.

Jenny Blum

Well, I married an author from Simon & Schuster. So I met him in the lobby at Simon & Schuster, where I went to get him to bring him in.

Tony Blum

[UNINTELLIGIBLE] traded the [UNINTELLIGIBLE] I got.

Jenny Blum

Tony, you cannot do trades with Anna because she's much younger than you.

Nicole Graev

Their kids are now four, five, and seven, Danny, Anna, and Tony, the oldest. When I went to Jenny's house in Connecticut, the three of them and a playmate were running around a large sunny breakfast room about to be picked up for a swimming lesson. It seemed wonderful. I wanted to stay for dinner.

Jenny Blum

My early 20s were like rungs on a ladder, editorial assistant, assistant editor, associate editor, editor, senior editor, just like that, dot, dot, dot, dot. I assumed I would be able to have it all. I was gonna have the job, and I was gonna have the kids, and I was gonna make it all work. When I just had Tony, when I just delivered him, I literally made calls to the office from the hospital. I didn't want to be disconnected from working.

I think there is such a thing as maternal instinct. And I think it kicks in. Even more than wanting to be at the office, I really wanted to be with this little baby. I don't know, Nicole. I think I'm really lucky with who I am and what I've done. And I don't think professionally I'm completely happy.

If I died like John F. Kennedy when I'm 38, am I going to say, "Started a career, bagged it?" I hope not. I hope I'll have something else. I think that's something you're going to have to grapple with.

Nicole Graev

So do you think of me somewhat as doomed? It's almost like I'm on a path only by virtue of being a woman. And I can't change that path.

Jenny Blum

Yes. You are doomed by your biology if you're gonna do, to my mind, the greatest thing you can do as a woman and have a child. You are doomed in a certain way. I think that's true. And I didn't understand it. And I still have a hard time with it. I do feel that it's unfair. I wish I could have my job back.

Nicole Graev

Doomed? Not exactly the word I'd wanted to hear. The whole idea of preparing for a family somehow seems so distant and unreal. I'm 22. A family hurt my head to think about. A family thew my map off the map. As I stood over the copying machine the next day, I tried to forget everything Jenny told me.

I spoke with a few more former assistants. Laurie Chittenden, who became an editor at 25 when she discovered a book that became a New York Times best seller. She told me to stay 'til midnight every night. Brooke Newman, who left Simon & Schuster in the late '60s to fly to Europe with a man she'd met the day before, told me, "Carpe diem." None of this helped me see a map for my own life. In fact, one former assistant, who seemed to have it made, Saul Anton, he's now a freelance magazine writer with a sunny duplex apartment in the West Village. He told me he's looking for the exact same thing I am.

Saul Anton

I really want somebody to give me a map. Usually, this person is my shrink. And twice a week, I go in there, I say, "Look, can I just have the map, please?" And my shrink says, "I don't have a map to give you. You have to write that map." I say, "But I don't want to write the map. If I'm going to have to write the map, I'm going to have to make the map, then I don't need a map."

Phyllis Levy

At Simon & Schuster, it was all exciting.

Nicole Graev

I end my story with Phyllis Levy, who had everything I ever wanted out of Simon & Schuster. She started there in 1955. She had the storybook publishing experience, what English majors all across this great nation have always dreamed it could be.

Phyllis Levy

There were people who first published D.H. Lawrence. There were people who started sentences with, "As my old friend Clarence Darrow used to say--" It was quite a world to be put in. Everyone was involved.

You could come into Jack's office at the end of the day. Nobody chose to go home because it was much more fun to be there. He had a bar in his office. Everyone came in, sat down, had a drink, and just sat, and talked about books and things. It was nothing to do with publishing today, absolutely nothing. It was total fun.

Nicole Graev

Allow me to provide some context. Editorial assistants these days don't even get to attend editorial meetings, so you can imagine my surprise when Phyllis told me this little story.

Phyllis Levy

One day, Malcolm Cowley, who was a consulting editor and who taught writing at the University of California, appeared in my doorway. He had come to visit. And he handed me a manuscript and said, "What do you think of this?" He gave it to me because I was only person under 60 in the editorial staff. And I took it home that night. And it was Ken Kesey's One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest.

Well, I came in the next day and went to the editorial meeting. I'd sat through all the previous editorial meetings in total silence, not daring to say a word. And I just said, "I've read the great American novel, and I don't care what any of you say. We have to publish this book." The way a kid would do. It was given to me, and I was the editor of that book then, just as an assistant editor.

Nicole Graev

Quick. Reality check. My real job this week--

[SOUND OF A PHONE BUZZING]

Nicole Graev

Yeah.

Geoff Kloske

Do we have any light bulbs?

Nicole Graev

Light bulbs?

Geoff Kloske

It's kind of dark in here.

Nicole Graev

I don't-- I can check the supply closet, I guess.

Geoff Kloske

Can you go get some light bulbs?

Nicole Graev

OK.

So there was Phyllis, schmoozing with literary icons, editing the great American novel. But the most amazing thing about her? She didn't even want the fate she ended up with.

Phyllis Levy

We're talking 1950s. I was programmed really-- we all were then-- to think of work as not very important and something you did to have a good time for a while until Mr. Perfect came along.

Nicole Graev

So what happened with the Mr. Perfect?

Phyllis Levy

Never mind. I'm not going to get into that. There were actually two Mr. Perfects, and both of them broke my heart. And that's that story.

Nicole Graev

Phyllis became a magazine editor. She worked in Hollywood for a while, jetting across the country, reading manuscripts. Now she's the books editor for Good Housekeeping. I looked at her, composed, elegant, sparkling, and thought about how much she'd been through, how much more she'd been through than me.

Nicole Graev

My whole life up until this point has been school. And in school, you always know that you're in the right place because when you're 15 years old, there's nowhere else you're supposed to be except high school. And you always feel like you're on this motorcycle, and you see the horizon in front of you, and it's the future. I always felt like hitting that horizon, like hitting that future was going to be like flying, like soaring. And I guess--

Phyllis Levy

Life is not like that. That's a very young person's idea of life. It's just not like that. There's not an epiphany. There's not something you know at the beginning that's your pa-- not at all.

You take each step where it leads you. And if you follow your heart with as much practicality as you have to have-- you have to have that. But I've always been someone who followed my heart. And probably if I've said, well, if you had it ever to do over again, would you change this, would you change that? And the thing is, to quote Hemingway, "Isn't it pretty to think so?"

I've even said to myself about the two great loves of my life, who, if I'd only chosen other people, I could've had families and children, blah, blah, blah. If I were given those same choices again, even knowing, even knowing that they ended badly, I would make those same choices again. Because I believe in following your heart, and that's what I do. And it's worked out just fine. I've had an awfully good time.

Nicole Graev

I thought over Phyllis's words later on, at the copier. The problem with following your heart is that the heart is not a compass. It spins around and around, sometimes pausing, wobbly, landing nowhere in particular for very long. My heart swept half-circles to California, swung back to going to grad school, and plunked down in front of the TV, not wanting to bother with either.

My heart once landed on a guy named John, whose heart landed on a woman in Belize. And then my heart didn't do much of anything for a while. But then it started back up again. It always does.

Ira Glass

Nicole Graev, professional assistant.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well, our program was produced today by Alex Blumberg and myself, with Susan Burton, Julie Snyder, and Nancy Updike. Contributing editors Jack Hitt, Paul Tough, Margy Rochlin, Alix Spiegel, and Consigliere Sarah Vowell. Production help from Todd Bachmann, Starlee Kine, and Sylvia Lemus. Musical help from Marika Partridge.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

If you'd like to buy a cassette of this program, call us here at WBEZ in Chicago, 312-832-3380. Or you know you can listen to most of our programs for absolutely free. Free, free, free on the internet at our website, www.thislife.org. That's thislife, one word, no space. Thanks to Elizabeth Meister who runs the site. This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

WBEZ management oversight by Torey Malatia, who wanders every day through WBEZ's hallways, saying,

John Bowe

There is not a sentient being for hundreds of miles probably. I am the only one wandering around here.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

John Bowe

Dear God, give me what I want, or I'm going to go shop elsewhere.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.