196: Rashomon

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

Larry Keeley is one of those guys with a job that, the more he tries to you explain to you what it is that he does for a living, the more you think, people pay you for that? He consults with companies about innovation, about how to organize themselves to be more competitive, more inventive, foster new ideas, that kind of thing.

So February of last year, he's giving a talk about all this to some executives who have gathered at a fancy golf course in Florida. And after the talk, two military men in the audience ask him to lunch. As they're being served, one of them asked what he knew about the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center building.

Larry Keeley

So he's asking me if I knew any of the details. And I said, no. And he started to tell me the gory details about the analysis of that bombing. And of course, what they use are people who go in afterwards and do forensic analysis of a calamity.

And what was fascinating about the forensic analysis is that the forensic teams didn't quite agree. Some said the bombs were placed 12 centimeters away from where they would have needed to be to destroy the major support column in the North Tower. Others said, no, no, no, you got it all wrong. The bombs were four centimeters away from where they needed to be to destroy that column.

Ira Glass

By the way, pretty alarming.

Larry Keeley

And it turns out that one of the guys I'm lunching with is a major general, George Close, a brilliant guy. And he turns out to be hand-picked by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to think through something called the revolution in military affairs.

When I got a little bit of explanation about this revolution in military affairs, they said, we're in the middle of one. And I said, OK. And they said, they don't happen very often, we think there's been maybe 12 of them in history. What that means is that everything that is normal and the way we engage, fight a conflict, and win it will go through a change.

So one of the early historic examples was the invention of gunpowder. And you think about the world of gladiator, and you see the kind of conflict that gun powder transformed forever. People that are rushing up to the enemy with their horses, wearing 300 pounds of armor and rushing up to the enemy and whacking him with something sharp. That was the nature of battle in those days.

Well gun powder comes along, cannons get cheap, they put them on wheels, they can haul them to the enemy's fortress. That's a revolution in military affairs.

And I'm sitting there listening to this and they've happened so seldom in the history of the world. Every time a revolution in military affairs has occurred in history, the party in power at the beginning has not been in power at the end. And they got a lot of historians at the Pentagon. And those historians had convinced the senior generals that we were in the midst of a revolution in military affairs with these basic principles.

Ira Glass

Which brings us to the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993. These particular generals were convinced that it was an example of this new kind of warfare. The way the thing was organized, through a web of operatives, the low-tech way it was carried out, the fact that it was on American soil and targeted at something so symbolic as the World Trade Center towers.

February of last year, these Pentagon officials were trying to think about how they should fight back. And they wanted to learn to think differently. They wanted to learn to think like their enemy. So they called on a bunch of guys in the private sector, like Keeley, for advice on how to think differently, how to change.

US military strategy right now is based on the idea that we will win wars through overwhelming force. That's the idea, overwhelming force. We will throw all the bombs, and planes, and missiles at the enemy, the best technology that money can buy, and a lot of it, just simply overwhelm them in a full-out attack.

And Keeley says that it was not clear if the Pentagon could change to something so low-tech and sneaky.

Larry Keeley

One of the things we have is money, material in spades. To challenge elite forces to be able to overcome a vastly superior enemy, with next to nothing. That is just completely the opposite of the way we think. And it's logical that we wouldn't think that way. Because we start with the presumption that we're the mightiest, and the biggest, with the greatest technologies.

Ira Glass

Right. You're saying that in order to fight these kind of sort of guerrilla terrorist actions, they have to become guerrilla terrorists.

Larry Keeley

I don't know if they have to become them, but they have to be able to think like them.

Ira Glass

Keeley says that the military brass that he talked to wanted to be able to do that, but also knew quite well how difficult that would be. It is hard to imagine the world from someone else's point of view.

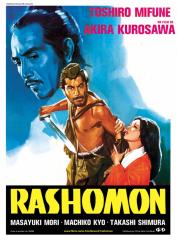

Today on our radio program, we try to do that. We bring you three stories, a kind of current events Rashomon. Each of the stories on our show today is something that you've heard of in the news, and we invite people with a different perspective, hopefully, than the one you already know.

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass.

Our program today in three acts: Act One, 1001 Arabian nightly newscasts. A Palestinian teenager from Chicago in that story explains why everything that you think you know about the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks is absolutely wrong.

Act Two, bombs over Baghdad. We hear the story of the Persian Gulf War, told by a family man from Baghdad who was drafted into Saddam's army against his will. Who had to explain to his 3-year-old son why those nice Americans were bombing their city, night after night.

Act Three, Toto, I don't think we're in Vietnam anymore. US special operations forces will lead the first part of the coming war that we are all bracing for. We hear how a simple half hour mission turned into a bloody all-day battle one of the last times they went out, just a few years ago.

Stay with us.

Act One: 1001 Arabian Nightly Newscasts

Ira Glass

Act One. 1001 Arabian nightly newscasts.

You know, asking what Arab Americans or Muslims think about recent news is as ridiculous as asking what Christians think. There is no one answer to that question, it is such a diverse community.

For this next story, we wanted to hear from somebody whose views do not necessarily agree with what most Americans believe. We did this specifically so that we could better understand why they believe what it is that they believe.

Our senior producer Julie Snyder visited with an 18-year-old Palestinian American named Rawah starting the week of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Rawah is a freshman in college. She's studying computers, living at home with her parents. She wears more traditional clothes at home, but jeans and a sweatshirt at school. She's religious enough that she always keeps her head covered in public. Here's Julie's report.

Julie Snyder

Whenever I visit Rawah's family's apartment, the TV is always on. They only watch the Arabic satellite channels, there are 10 or 15 of them from Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, the Emirates. There are movies, soap operas, there's even an Egyptian version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire that is almost exactly the same as ours-- but in their version, instead of cash prices, you win bars of gold.

There, as here, some newscasts are more reliable than others. Al Jazeera is sort of like CNN. Abu Dhabi is closer to Fox News.

Three days after the attacks, it's Rawah, her mother, brother, sister, brother-in-law, and me, sitting on the couch watching Abu Dhabi. The scene on the TV is like watching the news in a parallel universe. It's a reporter doing a stand up in front of the charred and collapsed portion of the Pentagon, just like any other reporter. Except he's speaking in Arabic, talking emotionally, and gesturing emphatically, saying the US doesn't have proof linking the attacks to Arabs and there seems to be almost no proof linking the attacks to Osama bin Laden, but that everyone in the United States is jumping to conclusions.

On hearing the news, Rawah's family nods in agreement. Her brother-in-law turns to remind me of the Oklahoma City bombing, where immediate reports pinned the blame on Arabs. The Arabic channels have been talking about this, and about Timothy McVeigh's recent execution, and how these attacks might be related to that.

He talks about various American militia groups I've never heard of that want revenge for McVeigh's execution

I tell him, I honestly don't know much about that.

He tells me it's reported all the time on the satellite TV.

Rawah

This is the 12 o'clock news.

Julie Snyder

This is Rawah.

Rawah

This report is saying that Israel is taking advantage of all the media turning to America and reporting what's happening. And they are bombing more homes and killing more Palestinians in Palestine.

Julie Snyder

In fact, in the first few days after the attack on the World Trade Center, Israel did step up military actions in the occupied territories. In the West Bank town of Ramallah, where Rawah's sister lives, Israelis launched missiles from helicopters and leveled a building used by a Palestinian intelligence agency, killing one person and injuring 120 others. Rawah's sister called to say that she and her son had been sleeping in their laundry room because it's the only room without windows.

Naturally, this was big news on Arabic TV. And while it was reported by Western news agencies like UPI and Reuters, because of the Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, it was hardly mentioned in American newscasts and newspapers.

Rawah and her family say this is typical. Americans who pay close attention to the news hear about Israeli actions against Palestinians. But most of us don't really know these things are happening, and don't get a sense of how severe they are. And this just makes Rawah mad.

Rawah

The only channel I don't see these things on is the American channels. I have the Syrian, the Lebanese, the Dubai channels, the Kuwait, the Saudi Arabia, the Iraq. So if all of these channels are bringing it, I'm sure it's not a lie. It's been confirmed on many channels.

Julie Snyder

When I first Rawah, she spent over an hour showing me around her house and explaining to me her views on the Israelis and their occupation of Palestine. We looked at articles she had written for the local Muslim newspaper. She played me a video she put together off the satellite TV, showing children brutally killed by Israeli shells, and Israeli soldiers shooting farmers at point blank range.

The footage was really graphic, filled with blood and body parts. You'd never see footage like it on American TV. Rawah's presentation even went multimedia.

Rawah

This is a Powerpoint slideshow. I have gotten the email, first in September, where the Israelis would start attacking the Palestinians. This is a picture of a boy in a hospital. This is a boy who was shot in the head.

Julie Snyder

The reason these stories don't appear in the American media, Rawah says, is because certain ethnicities in the media-- and that's the phrase she used, certain ethnicities-- don't want these stories to get out. Her family said the same thing to me. The man at the mosque around the corner from her house said it, too. After I'd spent a few hours with Rawah's family, the phrase "certain ethnicities" just shortened into "Jews."

The fact that they'd say this to a member of the supposed Zionist media conspiracy just shows how hard it is for them to imagine any other explanation for the way Arabs are portrayed in the news. I think it didn't even occur to them that it might be offensive.

And if all this seems bigotted and hard to swallow, consider how it looks from their side. Rawah hears about all sorts news from her sister, from Arabic TV, that is either downplayed or ignored in the Western media. What else could explain it?

Ali Abunimah runs a website where he tracks anti-Arab bias in the American media. He doesn't think there's a Jewish conspiracy skewing the coverage, but he says people believe it because, in their day-to-day experience, Israel seems capable of pulling anything off. Sure, Israelis see themselves as the underdogs, a tiny state surrounded by hostile neighbors. But from a Palestinian perspective, nothing seems beyond Israel's reach.

Ali Abunimah

I think there's an issue of power here. When you have an overwhelmingly powerful force like Israel and people who have lived under occupation-- people whose entire life is controlled by the whim of this power, whether you can get up in the morning, go to work, is up to the mood of the Israeli soldier at the checkpoint. Whether your house will be demolished is up to the Israelis. Whether you're allowed in or out of the country is up to the Israelis. Whether you're allowed to go from this village to that village is up to the Israelis. Everything is up to the Israelis.

So people experience the Israelis as a powerful, overwhelmingly powerful, force. And in fact, the Israelis have always tried to inculcate that in people, the myth of invincibility, the Israeli secret service, the Mossad, that it has this omnipotence. Which a lot of people believe, especially when they're in a much weaker position. You know, you might believe a lot of things.

Julie Snyder

And look at what Israel has already convinced people of, Ali says. Most of the West believes the creation of the state of Israel was completely fair and just. An inspiring story, refugees from World War II and the Holocaust who finally got a state.

From an Arab perspective, it's incredible.

Ali Abunimah

It's so different from the experience of Palestinians, who are often brutally and forcibly expelled. And people say, look how Israel got away with doing this to us and getting the world to believe something different. And if they can do that in that most fundamental instance, then what can't they do?

Julie Snyder

Ali is Palestinian and believes that the biases of the Western press aren't necessarily the things the reporters are even conscious of.

Ali Abunimah

Consider the fact that no foreign journalists covering Israel, Palestine, live in the occupied territories. I think there's one, I think the Economist's correspondent lives in Gaza, or at least used to.

So what happens, is that when a reporter goes there, they become, functionally speaking, an Israeli. You know, they live amongst Israelis. The children go to Israeli schools. They wake up in the morning, they go and get their cup of coffee, they're surrounded by Israelis. And so their fears become those of Israelis.

I remember an NPR reporter being interviewed about how she copes with the fear of suicide bombings.

And she said, well I and my friends, you know, we go out a bit less. She was speaking in the first person. So there's no reporter who can speak in the first person as to what it's like to be a Palestinian.

So there's an issue of perspective. It's not that there's conscious bias. But if you're living in one place that's totally different, that's like a first world environment, as West Jerusalem is, you're going to have a very different perspective.

Julie Snyder

A few days after the September 11th attacks, I gave Rawah a tape recorder to keep a kind of audio diary of her life. About a week into it, she recorded this.

Rawah

OK. Right now it's 8:05. And as soon as I got home, my mom told me that on the Arabic satellite they brought that about 4,000 Israeli people that are employed in the World Trade Center did not go to work on Tuesday. And Ariel Sharon was supposed to be in a meeting in New York on Tuesday, but he canceled it.

Also, there were Jews, photographers, on top of the building, a few buildings. They were getting ready to take pictures. So the assumption now is that the Jews are the ones who did it.

Julie Snyder

A couple days after Rawah recorded that, I was invited to her house for a lunch being held for her sister-in-law's sister who was visiting from Jordan. Lots of people, huge trays of food were laid out on the coffee tables in front of us, and toddlers and kids swarmed around.

At the very end, as we were clearing the dishes, one woman asked me, how come the government and the media are always blaming the Arabs for everything, when they have hardly any evidence? Have you heard about the 4,000 Israelis who didn't show up for work at the World Trade Center on Tuesday?

And then again, later, after all the women had gone, Rawah's brother-in-law came over. He runs an Islamic community group and wanted to give me some press releases that have been faxed to him.

He then told me that it probably didn't matter, and that I wouldn't report it, anyway. But had I heard about the 4,000 Israelis in the World Trade Center?

It's not clear how widely believed this rumor is. It appears to have originated on the Hamas website-- yes, they have a website. And then was spread on Al-Manar, the Lebanese TV channel-- not on the news broadcast, but on the call-in shows. Viewers would phone in and repeat the rumors as the truth.

There's no polling of Arabs or Arab Americans on these kinds of things. But of the five representatives of Arab American organizations I spoke to, all of them had heard of this rumor, and all of them said it's not widely believed here in the States. Lots of rumors get more play.

For instance, there was a rumor a few months ago that McDonald's was donating its profits to Israel. A spokesman for the Arab American anti-defamation league in Washington says he got over 4,000 emails about that rumor. By comparison, he's received only 15 or 20 emails on this latest one.

One reason Rawah's family believes the rumor is true is this: who benefits from the attacks on the World Trade Center? Not the Arabs, they say, not the Muslims.

Instead, Rawah says that up until this point, the war in the Middle East has been between the Arabs and Israelis. But the September 11th attacks, she says, will necessarily bring the US into that war, turning an Arab-Israeli war into an Arab and American war. As far as she's concerned, this is what Israel has wanted all along. This is why, she says, Israel would attack the US but frame the Arabs for the crime.

Rawah

Till now, no Israeli name has been mentioned of one of the victims. No Jews, nobody has been reported that they were hurt.

Julie Snyder

But you know what? Actually, after you and I talked, I went through and looked at names of people who were missing, and there are Jews missing.

Rawah

There aren't?

Julie Snyder

There are.

Rawah

There are? That were killed in that building?

Julie Snyder

Yeah.

Rawah

Well, how about the employees that did not go to work that day?

Julie Snyder

If it was true that there were 4,000 Israelis who worked at the World Trade Center and didn't show up for work that day, that would mean that one in 15 people who work at the World Trade Center are Israeli. Which is just not true. You know what I'm saying?

Rawah

I see what you're saying. And I don't know who did it, exactly, and no one knows yet. Because no one in the world, yet, have any real evidence of who attacked the World Trade Center.

Julie Snyder

At this point, 130 Israelis are still officially unaccounted for. The confirmed Israeli deaths are these: two passengers on the hijacked planes, and the body of a third Israeli found at the World Trade Center, and buried.

Ali Abunimah says no one he knows believes the rumor about the 4,000 Israelis. But, he says, part of the rumor's appeal is that it takes the heat off Arabs.

Ali Abunimah

You know, one of the first feelings I had, and many others, is please God don't let this be someone from the Middle East. We don't want it to be, we disown, we renounce this act. This is a horrific atrocity, a crime against humanity was committed in New York.

So saying it's a Zionist conspiracy is a way to dissociate yourself from it completely. You know, if people supported it, they'd be saying, yay, you know, strike one for the Muslims. No one is saying that. They're all looking for a way out.

Julie Snyder

Rawah just can't believe a Muslim could have been behind the attacks. The Koran wouldn't allow it. Besides, she says, where's the proof?

And this actually seems to be the biggest difference between the way people from Arab countries see recent events and the way most Americans see them. It's not about the rumors, it's about Osama bin Laden.

Most of the Arab Americans I spoke with are still waiting for proof linking him to the attacks, for some sort of hard evidence to be released to the public. And they're skeptical it'll ever come.

Rawah believes bin Laden is just a convenient scapegoat.

Rawah

Now, I wouldn't be surprised if this Halloween you have kids and people dressed as Osama bin Laden. Strongly believe so.

I went to Dominick's the other day and I was shopping and I see all these Pumpkins and costumes. And there's the first thing that came into my mind. Because Americans now are afraid of something called Osama bin Laden. Or something that is called Mohammed or Islam or Arabs.

Julie Snyder

Rawah believes Israel is all-powerful, and capable of everything she sees as bad. Most Americans wouldn't agree with her about that.

Meanwhile, from an Arab point of view, we're doing the same thing with Osama bin Laden. He seems all-powerful. We're ready to believe it was him, even if we haven't seen the greatest proof. Maybe everyone needs a boogeyman.

Ira Glass

Julie Snyder.

Act Two: Bombs Over Baghdad

Ira Glass

Act Two. Bombs over Baghdad.

Issam Shukri is an architect living in Toronto. But during the Persian Gulf War, he lived in Baghdad, where he grew up.

His experience of the war was of course very different than most of ours in this country. He remembers clearly how he learned that his country had invaded Kuwait.

Issam Shukri

Me and my wife used to work in two different rooms in the same sort of building. And she always listened to Kuwaiti station, the national Kuwaiti station, because it has some more fun songs and mixture of songs, and stuff like that.

But anyway, so she was trying to find that station, but she couldn't. She said, Issam, it seems there's something wrong with the radio, I can't find that station.

So I start to flip through the stations. And I put it on our Baghdad station, and, boy, I started to hear the marches and the military music.

Ira Glass

Did that automatically mean you knew that there was trouble?

Issam Shukri

Yes. That was the government's sort of announcement, in music, to times of trouble. We sense it when we, for instance, hear emotional love songs, we think that the regime is taking a break a little bit.

So at the time, we heard that and instantly we knew that there was a military or some kind of problem.

I heard about the invasion by dashing out into the street, and saying, what happened? And people, in a lower voice, well Saddam invaded Kuwait. And he's calling people to go and fight over there in the front.

And I said, I sort of struck my head and I said, not again.

Ira Glass

Had you served in the Iran-Iraq war?

Issam Shukri

Yes, I served three years, actually.

Ira Glass

And that war, of course, an incredibly bloody war. Estimates of the dead range up to 1.5 million. Iraq used chemical weapons in the war.

Can you talk about what it felt like to know that you were being called up again to fight in this conflict for somebody who you didn't support?

Issam Shukri

Well, I don't know. Ira, it's the most individualist, as well as a collective, miserable experience that you will ever have. Because you are facing, actually, not one enemy. You are facing two enemies-- one in your back, and one in your face. And when you turn to run away, you see the back enemy trying to shoot you. That is the government of Iraq, right.

I couldn't picture myself putting on the same uniform and fighting for a regime, a bloody regime, again. So that was my feeling.

And the next day I had to go to that military center and join the forces. But as I was an architect, I was actually allocated to the back of the front, and inside the city of Baghdad.

Ira Glass

Oh so you were very lucky.

Issam Shukri

I was, actually. But some of my classmates, they were sent out to the front. And some of them faced their deaths there, they were killed.

Ira Glass

Did they have the same kinds of feelings about Saddam that you did? That they didn't like the regime?

Issam Shukri

Ira, 100%, 100%, I will tell you.

Ira Glass

Talk about the air strikes. Could you talk about what that was like? You were in Baghdad when the US started its 38 day air campaign against Iraq.

Issam Shukri

Right. Actually, Ira, at the time we were waiting because James Baker, at the time, warned Iraq that, we are going to put you back in the Middle Ages. And everybody knew about that, but nobody believed it.

Ira Glass

Nobody believed it?

Issam Shukri

Yes. Yes, we didn't believe that it's going to happen. It's over 100 countries are gathering their forces with an unprecedented show of force in the human history, against 22 million people. We couldn't believe that this could be something true. I couldn't believe that the representative of the most so-called civilized country would utter such nonsense. Forgive me for that.

Ira Glass

So where were you when the bombing campaign began?

Issam Shukri

Yeah, I was in my home with my wife and my three-year-old son. And I was renovating my house. I was like two years, three years married to my wife.

And I was sort of dividing my family home into two little homes. One is for my sister and one is for my family. And as a show of, you know, emotional support, we all slept-- we had mattresses on the floor in my living room, which had doors open because I was renovating at the time. You know, I've brought a lot of paint to paint my living room.

So anyway, we slept, and that night, the night of the 17th of January, in my living room, and we sort of kissed each other and we fell asleep. And exactly at 2 A.M. we all woke up and the ground was shaking violently. And it was like a deep, deep, sort of echo happening, coming down from the ground. And the streetlights were on at the time, and in five minutes, all the lights were out.

And we, at that minute, we were certain that this is the war and we're back again. We're facing death all over again.

I, personally, Ira, I'm not ashamed of this-- I started to shake. My hands couldn't hold anything. I grabbed my--

Ira Glass

Take a second.

Issam Shukri

I grabbed my little kid. And he was crying, he didn't know what was happening. I remember my son, when he heard the B-52 over his head. I put my hand on his heart and I felt his heart bumping like crazy.

And ironically, I went to the wash the next five, six times in five minutes. You know, when you have this kind of stress, I needed go to the wash room. As mundane as this is, but I need to tell the Americans about it.

The fear is very, very frightening when you're expecting your death. It's much more frightening that when it happens suddenly, if you're asleep, or if you're embarking on your work, or whatever. But when you're expected minute by minute, second by second sometimes, it gets like a torture. So we were literally tortured.

And we started to wander with the streets. I looked around in my neighborhood. And, by the way, our neighborhood looks pretty much like any American or Canadian neighborhood. You know, row houses or individual homes, with the front yards very nicely done. You know, people that has the same qualities of life. The difference is that they live in constant fear.

Ira Glass

And you were with your three-year-old boy.

Issam Shukri

Right. Well actually, I was very worried about this guy, because he was very young. And you know when fear, when you start your life by experiencing fear and bombing, it would leave scars in your soul for the rest of your life. And I think he's fine now.

But he kept asking me, why are they doing this to us? What have we done?

And I couldn't find the right answer because he was very young at the time. I couldn't go into deep political analysis of what's going on. But I told him, there is a bad guy who did something wrong. And there are some judges of the world who wanted to take the law by their hand, and then they come and punish him. And then I stop for one second, and say, but they are punishing us. But we are scared, he's not scared.

Ira Glass

Did he ask, why are they bombing all of us if they're just trying to get this bad man?

Issam Shukri

Well, Ira, I didn't try to justify what the American forces were doing. To tell you the truth, I'm not going to polish my words. I told him that, you know, after days and days of bombing I at first told him that, well there are some judges who are going to catch this man. And, you know, he's an outlaw, they're going to put him in jail. I try to make things like a story to his age.

And then after that I start to feel frustrated, myself, because I see people slaughtered in front of my eyes. And Saddam comes out in the screens, laughing with his ugly face. So I started to tell him, well, those judges are sometimes more severe and sometimes they hit hard that the people themselves will suffer some injuries. But, again, that's OK. Probably in the end, they will catch him.

But it never happened. And now he knows that it's not going to happen, neither in Iraq nor in Afghanistan, nor in anywhere in the world.

Ira Glass

Was there a part of you which hoped the Americans would succeed and liberate Iraq from Saddam Hussein?

Issam Shukri

To tell you the truth, I hoped for that. But I felt deep, deep in heart that they're not going to catch this person. I've always doubted that. And not only me, all the people in Iraq doubted that. Because there is always history that tells you lessons.

And there is the fresh memory when Saddam used the chemical weapons against Halabja-- which is a northern, very, very peaceful city-- in 1988, and killed 5,000 people in two hours. Nobody in the West raised a finger. Nobody called him a terrorist, nobody called him a tyrant.

But when he touched a state that is a strong ally to the West, a state that is very rich in oil. So we didn't have really trust to the West. It's a feeling that those people do not care about other nations. They can bomb any city, any minute, any time, without warning.

Ira Glass

And what did you think about the United States at that time? Did you hate the United States for the bombing? Did you feel a mix of feelings about it, because you hoped that they would come in?

Issam Shukri

I didn't like the United States. As a government, as a military force-- not the people. I saw cruise missiles falling on buildings that are exactly-- unfortunately, I would say that it looked exactly to me like the World Trade Center. I mean, when I saw the World Trade Center, those airplanes crashing into it, the first thing jumped into my head was when I saw one of the buildings-- I was driving from one part of the city to the other-- and I saw one of these building hit by a cruise missile. But some of these buildings where inhabited by civilians.

So, I do not hate, I don't like to use this word, but I was mad, I was angry at the United States government. Because it uses a lot of force, inhuman force, to punish very poor people.

Ira Glass

And were you also angry in Saddam for putting you all in this position?

Issam Shukri

Oh, in that respect, we hated Saddam. I would definitely use that word.

Ira Glass

Issam Shukri in Toronto. In his spare time, he does a little work with a group that's trying to lift the economic sanctions that stop food and medicines from going into Iraq.

He points out that 5,000 civilians are dying every month that the sanctions continue. Five thousand a month, every month, for the past 11 years.

Coming up, the war ahead, and lessons from a half hour battle that got out of hand in 1993. In a minute, from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International, when our program continues.

It's This American Life, I'm Ira Glass.

Today on our program, current events Rashomon in which we look at familiar news stories from unfamiliar points of view, hoping that might shed some light on things, give some perspective on troubling events. We've arrived at Act Three of our program.

Act Three: Toto, I Don't Think We're In Vietnam Anymore

Ira Glass

Act Three. Toto, I don't think we're in Vietnam, anymore.

We've been told that the first part of the coming war on terror will involve US special operation forces tracking down suspected terrorists. Perhaps it would be helpful to remember another mission like that in this moment.

In the early 1990s, there was a UN peacekeeping mission in Somalia. In that country there were a number of rival factions competing for power.

In June of 1993, a local militia leader named Mohamed Aidid ambushed and killed 19 Pakistani soldiers from the UN mission. The Clinton administration dispatched a squad of special operatives to capture Aidid and dismantle his military organization. The squad consisted of two elite military teams, the Rangers and the Delta Force. On October 3, 1993, their mission was to capture two of Aidid's top commanders.

Mark Bowden wrote a book about the battle called Black Hawk Down. He talked to producer Alex Blumberg about that day and the mission to capture those two men.

Mark Bowden

And they had been spotted speaking at a rally in Mogadishu earlier that morning, and had been observed by spies on the ground and in the air traveling to a house in the center of Mogadishu, in an area called the Bakara Market.

And so General William F. Garrison, who was the leader of Task Force Ranger, authorized a raid which was to swoop in very quickly on this house and arrest these two guys and anyone who was with them, and bring them back to the base.

Alex Blumberg

And the mission, it didn't exactly work out the way it was supposed to.

Mark Bowden

No. The mission was envisioned as taking about 30 minutes-- or basically 30 minutes on the ground and maybe another 30 minutes to convoy the prisoners out of the city.

Alex Blumberg

In the end, how long did it end up taking and how many lives were lost?

Mark Bowden

In the end, the battle lasted about 15 hours, through a long night and into early the next day. Eighteen American soldiers were killed. It was the most significant firefight that American soldiers have been involved with since the war in Vietnam.

The way the raid was set up, the Delta Force operators would hit the ground first. They ride on benches on the outside of these little helicopters-- AH-6s, they call them Little Birds-- and are literally put right down in front of the house. They land right on the street. So the Delta Force operators were inserted in that way.

And then the bigger Blackhawk helicopters come in. The Blackhawks are too big to land on the street. So they hover overhead, and the Rangers rope down to each of the four corners of the block where this operation was taking place.

Alex Blumberg

Well, what was the first thing that didn't go as planned?

Mark Bowden

Well as the Rangers roped into the four corners, one of the young rangers, a fellow named Todd Blackburn, actually missed the rope and fell 70 feet from the helicopter to the street. You know, this was the most serious injury that any of these units had sustained since they'd come a month before. And it caused certainly a great deal of alarm within his little Ranger unit there.

And it set in motion a chain of events that kind of just slowed the whole process down. Not a lot, but a little.

Alex Blumberg

One of the very first things in the book is when you're talking about, they're hanging from these helicopters on these ropes, they're seventy feet above the ground, they have to slide down these ropes, and then sort of establish their position. And just the confusion of it all was just-- like, what do they see as they're coming down?

Mark Bowden

Well, initially, as the men descended the ropes to the street, they could see almost nothing. Because the helicopters, the Blackhawks are so powerful, they kicked up huge clouds of dust. So they're roping down in a dust storm, so they can't really even see much past their nose. And they're hearing, for the first time, pretty heavy fire. Learning the sound of bullets that pass very closely make a loud, cracking noise, like a piece of hickory being snapped.

Alex Blumberg

So the only way you can tell how close a bullet is is by the sound it makes?

Mark Bowden

That's what they tell me. I've never, fortunately, been in a situation where people have been shooting at me. But there's sort of a whooshing sound that you hear if the bullet passes somewhere in your vicinity. But if it's close enough to you, you hear what's essentially a little sonic boom as the round goes past you. And, of course, they say the one that hits you, you never hear.

Alex Blumberg

And most of the guys were learning this for the first time on this mission.

Mark Bowden

That's right. These are very young soldiers, they're well-trained, and very cocky, and very capable. But they had never been exposed to fire like this. And they had never seen the guys next to them suddenly start to drop.

Matt Eversmann, who was put in charge of this mission for the first time, one by one the men in his unit scattered around the street where they'd just landed are beginning to sustain injuries.

Alex Blumberg

They get shot.

Mark Bowden

They get shot, right. One of them gets his thumb shot off, another gets shot in the shoulder-- he just starts seeing his men go down. So this was a very, very dangerous place to go.

The rules of engagement were that the men, the American soldiers, were not allowed to shoot at someone unless they were pointing their weapons at them. And so the Somalis knew the rules of engagement. So they mingled in with the angry crowds, who were not armed, so that they could fire at the Rangers without the Rangers being able to shoot back at them.

There was literally a scene where one of the Rangers was confronted with a Somali gunman who was laying on the ground. And he had children sitting on top of him. And I think he had a woman standing right in front of him. He had basically surrounded himself with non-competents so that he could lay there and shoot at the Rangers without being shot at himself. And actually what the Rangers in the situation did, was lay down a line of fire right in front of this man-- the children and the women fled very quickly, and then they shot the gunman.

But eventually, they were under so much fire that the rules of engagement were just dropped. Because they realized that they had to shoot back. If they didn't, they weren't going to survive. So some of these young men were in the position of having to shoot at crowds of people in order to avoid being killed, themselves.

Alex Blumberg

So then, what happened after that?

Mark Bowden

Well they proceeded to evacuate Todd Blackburn. The Rangers fanned out and formed the perimeter like they were supposed to. They began coming under more and more fire as the minutes went by. The Delta Operators arrested the people they were looking for. They found them and handcuffed them and were leading them out of the building, when one of the Blackhawk helicopters that was still circling overhead, was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade, and crashed about four blocks away.

[RADIO]

Mark Bowden

All of the men involved in this mission are communicating with themselves by radio. All of these conversations were tape recorded. One of the things that I found remarkable about listening to the audio tape is that you can hear the intensity of that moment. When that Blackhawk helicopter crashes, you hear men shouting into the radio, we've got a Blackhawk down. And you can hear the panic, almost, in their voices.

[RADIO COMMUNICATION BETWEEN BLACKHAWK AND BASE]

Mark Bowden

To them, if you're on the ground in a city with literally thousands, if not tens of thousands of people surrounding you and shooting at you, your faith in getting out of there alive rests largely on those helicopters overhead. They are symbols for you of the fact that you're there representing the most powerful military force in the world.

When the Blackhawk was shot down, that was the defining moment of this episode. The idea was to insert the men, take the prisoners, load them on vehicles, and drive them out of the city, and everyone would come back and have a barbecue. But once that Blackhawk went down, everything changed. Because now they had men down on the ground, either dead, wounded or fighting for their lives, and they had to try to rescue those men who had just crashed.

[RADIO COMMUNICATION BETWEEN BLACKHAWK AND BASE]

Alex Blumberg

And so basically the convoy, which originally had been planned to just go back to the base with the prisoners, now has a totally different sort of mission.

Mark Bowden

Right. Well this became one of the major phases of the battle, and certainly the bloodiest phase. Once the Blackhawk was shot down, the orders were for the convoy to load up the prisoners and then drive to the neighborhood where the Blackhawk had crashed. And the idea was then to rescue the men who had been aboard the helicopter and then drive out of the city.

But the problem was that the streets of Mogadishu are like a maze. And at this point, there are Somalis setting up burning barricades, and organizing ambushes at intersections. So as the convoy began to try to make its way to the downed Blackhawk, it got lost.

[RADIO]

Mark Bowden

It became a tragic comedy of errors with the pilots in the helicopters overhead. And there was a Navy plane, a P-3 Orion, flying high overhead, all of them trying to give directions to this convoy. But because of the, in some cases, the relay system of communicating to them, the people in the vehicles would get the instructions too late to take advantage of them.

So for instance, someone high overhead would say take a left. And by the time that communicated to Danny McKnight in the lead vehicle, they'd already passed the point where they were supposed to take a left.

[RADIO COMMUNICATION BETWEEN BLACKHAWK AND BASE]

Mark Bowden

The men in the vehicles in the rear of the convoy didn't even know what was going on. A lot of them still thought they were driving out of the city because no one had communicated to everybody down the line exactly where it was they were going and what they were trying to do. So you have these men holed up in these vehicles, one by one getting injured or killed, and not knowing where they were going, why they were making the turns they were making.

Alex Blumberg

And it's not something where you can stay inside. Like, a Humvee isn't actually that much protection, it turns out.

Mark Bowden

Right. The convoy was made up of two five ton trucks, flatbed trucks, with the prisoners in the back, and, I believe, six Humvees. And they discovered that rounds could go right through the skin of the Humvee.

For instance, one of the Humvees took a direct hit from a rocket-propelled grenade, which penetrated through the side and exploded in the back, blowing the men who were in the back of the Humvee out the rear of the vehicle, out onto the street. A couple of those men were killed, two or three others were severely injured.

Whenever anything like that would happen, the convoy would stop, the men would all have to pile out. They would try to rescue the men who were injured, get them back on the vehicles, start up again. Every time they would stop, they would come under heavy fire. Until finally, more than half of the men on that convoy were either dead or injured.

Alex Blumberg

And it's especially heartbreaking when you read, because several times the convoy swings a block away from where the trapped people are.

Mark Bowden

Yeah. And it just shows you how chaotic the situation was on the street. There was this feeling expressed by one of the Air Force combat controllers who was in one of the lead vehicles, his name is Dan Schilling-- he couldn't understand what was going on, and he just believed they were going to keep driving around until they were all dead.

Alex Blumberg

You know, at this point in the book, you're sort of midway through the book, one of the things that becomes very clear is that it's almost as if the entire city now has-- I don't want to say turned against, because I feel like maybe that's not the right word--

Mark Bowden

No, it's exactly the right word.

Alex Blumberg

Is it?

Mark Bowden

I mean, the Rangers said that they felt like it was kill an American day in Mogadishu. There was so much anger and hostility toward these American troops, that it virtually was true. That they were trapped in a city where everyone in the city, it seemed, was trying to kill them. And this is not just a normal city, this is the most heavily-armed population, probably in the world. And so they were under intensive fire from 360 degrees.

Alex Blumberg

Do you think they had a sense of the enormous hostility that was pent up out there?

Mark Bowden

I think that they probably were aware that there was hostility against them, but they couldn't have imagined the intensity of it.

You have to remember, these are the best-trained soldiers in the world. They have the best equipment, they have these helicopters, which are absolute marvels of military technology, to support them. So they had, I think, a really cocky attitude. The idea that they would find themselves so outnumbered, and outgunned, and at a disadvantage, in a place like Mogadishu where they viewed the people they were fighting against as just a ragtag bunch of irregulars who wouldn't know how to put together an assault if their life depended on it-- now, though, they found themselves in, really, a predicament from which a lot of them had no reason to expect that they were going to get out alive.

Alex Blumberg

You know, clearly, from what everybody's been saying about the current situation in Afghanistan, is that the military part of the response is probably going to involve-- almost certain to involve-- special operations forces, some of which may be already on the ground in Afghanistan. Pretty much exactly what you're describing.

Mark Bowden

Well, in fact involving the same units and in some cases the same men.

Alex Blumberg

What thoughts do you have about that?

Mark Bowden

You know, what I hope the book Blackhawk Down does is sober people up to the reality of combat. And I'm not arguing, and I don't think the book argues, makes a pacifist argument, that we shouldn't be using military force. I think we're clearly in a position right now where will the moral obligation is to use military force.

The problem with the Battle of Mogadishu was, that none of the civilian leadership in the United States, from the President to the Congress, had imagined that these raids could turn out with so many people killed and injured. So their response, when this happened, was one of horror, that this was a disaster.

And so immediately, President Clinton called off the military mission in Mogadishu. But from a military perspective, the military objective was to capture Hasan Awale and Omar Salad. They were both captured and evacuated from the city and were in custody at the end of the day. And I think it was galling to the military, particularly to the men who took part in this, to have this mission viewed as a debacle. Because they felt that they've been successful, and they felt that after so much sacrifice, their strong desire was to stay and finish the mission, if only to honor the memory of the men who had been killed accomplishing it.

Alex Blumberg

Mark, did the Pentagon, did they study this battle? Did they sort of look at it a year or two later and just sort of say OK, what happened here, what went on, what are the things we can learn from this?

Mark Bowden

Well, much to my amazement, I don't think that the Army seriously studied this episode at all, this battle at all. It just boggles my mind, when you consider that this is probably the only instance of serious, real world fighting that American soldiers have had to do, certainly since the Persian Gulf War. And there was nothing like this even in the Persian Gulf War.

And you would think, just from a standpoint of evaluating the effectiveness of weaponry, of armor, and tactics, that they would want to examine very carefully what happened here. You know, I found myself in the position when I began working on this book, of being the first person who had attempted to really examine exactly what happened in detail.

Ira Glass

Mark Bowden. His account of the Battle of Mogadishu is called Blackhawk Down. Of 160 Americans in the fight, 73 were injured, 18 died. A conservative estimate of the number of Somalis dead-- 500 to 1,000.

Credits

Ira Glass

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. Support for this program comes from PBS, presenting Life 360, a new series that explores life's surprises. Friday nights at 9:00, local times may vary.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

WBEZ management oversight by Torey Malatia, who wishes our format included more of--

Issam Shukri

The marches, and the military music.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of this American life.

Announcer

PRI. Public Radio International.