207: Special Ed

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

Edward was just a little boy when he was switched from regular classes to special ed. It was kindergarten, and he viewed the move as a big step up.

Edward

I thought it was cool because when you think of the word special meaning special, you know, like good, a good thing?

Ira Glass

Yeah.

Edward

And, with my name being Edward, I thought it was kind of built for me.

Ira Glass

Oh. Like, Ed meant you?

Edward

Yeah.

Ira Glass

He was Ed. Of course he was going to special ed. And he didn't really figure out what special ed classes really meant for years, until one day in junior high school riding the school bus.

Edward

And one of my friends, who was younger than me, on the bus, asked me to help him with his homework. And I noticed he had harder homework than we did.

Ira Glass

Why? What do you remember about his homework?

Edward

Because he was doing like, I think it was, timetables and division-type things. And ours was addition and subtraction, still, and we were a couple of grades higher than he was. And the spelling words was like, they looked like high-schoolers would have a spelling word, kind of thing like, forbidden and probably some more words harder than that, kinda.

Ira Glass

Like the word forbidden. And what were you guys doing?

Edward

Cow, sheep, sleep. It kind of got me mad. And I just kind of thought we were all regular. And then, that day, I saw kind of like a divider kind of thing.

Ira Glass

I would think that, that would be very hard.

Edward

Well, yeah, because you kind of think of yourself as regular until these teachers and people of high authority are telling you you're not the same as everybody else. So you have to figure out OK, so why am I different?

Ira Glass

A lot of kids in junior high school and high school feel different. But to be told no, it's not your imagination, you are different? This moment is something a lot of kids in special ed get to at some point or another: a shocking moment of understanding that they are not the same as other kids and that everybody else knew that long ago. They knew it when they didn't.

Holly

We were doing a project in first grade. Putting a snowman-- actually, we had to put cut-out objects, like cut-out circles, and put it on there, and put stuff on it.

Ira Glass

Holly is a high school student in Chicago. She's 18.

Holly

And I was doing that. And I didn't cut one. And I accidentally unscrewed the top of the glue, and it spilled all over. So I had to clean it up. And then she put me in the corner and yelled at me. It was really embarrassing. Everybody was laughing. It was kind of hard. So that's the [UNINTELLIGIBLE] I really remember. I guess she thought I was stupid in some way. I felt bad about myself at that point because I realized that I really was different from everybody else.

David

I was about, maybe, 14 when I was placed into a special ed class because my reading skills were real low.

Ira Glass

David is also a high school student here in Chicago. He's also 18.

David

When I was placed into the special ed program, you know, I felt sad and lonely. For me, a man, like I was a slow person that had problems learning, like a mentally problems.

Ira Glass

Today on our program, stories of people who were told that they're different: some who were comfortable with that, some who did not understand it, some who understood it and did not like it. We bring you stories of the developmentally disabled. It is a very different kind of show for us with voices and stories that usually do not make it to the radio.

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass. Our show today in three acts. Act One, Get On The Mic. In which we hear the story of what happens when you hand microphones to developmentally disabled people of various sorts and then send them out with camera crews to interview anyone they want on the streets of America. One thing that turns out to be on the minds of the disabled, same thing that's on your mind and mine, TV.

Act Two, Black Hole Son. In that story we hear from a mother and her son who, at three, became mesmerized with black holes and Stephen Hawking, an obsession which gave way to bunnies and flowers.

Act Three, Walkout. Veronica Chater tells the story of her own brother, Vincent, who one day quit his job at an assisted learning center, and then quit everything else, mystifying everybody in his life. Stay with us.

Act One: Get On The Mic

Ira Glass

Act One, Get On The Mic. Here's a typical moment from the film, How's Your News? The film is a documentary in which five developmentally disabled people travel across America in an RV interviewing people they meet along the way. When they get to Texas, one of the reporters, Sue Harrington, is at a cattle auction talking to an auctioneer, an older guy wearing a cowboy hat. There's all sorts of talk about prices and cows. And then Sue, apropos of absolutely nothing, comes out with this question.

Susan Harrington

Sir, have you lately read any good books or seen any good movies that you could recommend to us?

Auctioneer

No, I ain't read any good books lately. I can't remember the name of the movie I saw the other day. I saw Message in a Bottle, and that was a dad gum good movie, I thought, kind of a tear-jerker.

Susan Harrington

Oh, really? Really? It's a good one? You know, that's the first good review I've heard for that one.

Auctioneer

Well, I'm kind of sentimental. I cried in Old Yeller too.

Ira Glass

Now, How's Your News? team has an uncanny knack for bringing the sentimental out of people they meet. Arthur Bradford, who led the How's Your News? team across the country, he first got to know them in 1993 at a camp for disabled adults called Camp Jabberwocky. He was a counselor there teaching a video class. And as part of the class, he would take the campers out to do man-on-the-street interviews.

They did that for a few summers, and then decided that it might be exciting and fun to try to do their interviews on a two-week, cross-country trip, which became this movie. Arthur says that, from the start, it's been interesting to see how people react to the disabled reporters.

Arthur Bradford

What I've noticed is that, when someone with a disability approaches someone on the street, this is without a camera or anything, that person sort of settles into OK, I need to, I guess basically, talk down to this person. It's sort of like they're talking to a child, I would say. But what I like about when you give them a microphone and a camera is that, suddenly, the people take them a little more seriously. And I would say they, maybe, give them a little more respect.

Ron Simonsen

Hello. My name is Ronnie. I'm from How's Your News?. What's your name, sir?

Curtis Tuldgrave

Curtis.

Ron Simonsen

Curtie, who?

Curtis Tuldgrave

Tuldgrave.

Ron Simonsen

What do you do, Curtie?

Curtis Tuldgrave

I work for the post office.

Ron Simonsen

Yeah? Tell us about the post office.

Curtis Tuldgrave

The post office is a good place to work.

Ron Simonsen

Yeah? Yeah, I get my mail there at the post office. I love getting mail. Have you met any famous people?

Curtis Tuldgrave

No.

Ira Glass

This reporter, Ron Simonsen, asks nearly everybody who he interviews if they've met any famous people, especially if they've met Chad Everett who used to star in Medical Center. Ron is a big Chad Everett fan and wears a homemade Chad Everett sweatshirt through parts of the film. Here's Ron interviewing a woman in Las Vegas.

Ron Simonsen

I'm Ronnie Simonsen reporting from Las Vegas. Today, I'm with a fabulous singer, Jennifer Holloway. Tell me, Jennifer, how's it feel to be a singer?

Jennifer Holloway

Fabulous. I enjoy it.

Ron Simonsen

Have you met any famous people?

Jennifer Holloway

H I have: Tanya Tucker. I've met--

Ron Simonsen

Have you met Chad Everett?

Jennifer Holloway

No, I have not.

Ron Simonsen

You know who he is?

Jennifer Holloway

Yes. Yes, I do.

Ron Simonsen

I do an impersonation of Chad Everett.

Jennifer Holloway

Well, let's see it.

Ron Simonsen

All right. This is Chad Everett.

Jennifer Holloway

OK.

Ron Simonsen

You've got class, lady. My name is Chad Everett. You know, I was the star of Medical Center.

Ira Glass

There are moments during How's Your News? when things happen that, in another movie, might seem like they're mocking the people on camera. But, in this context, they don't, partially because it's clear how well the filmmakers know the reporters and love them. They were counselors and campers together in the RV. They've known each other for years, taking a road trip.

Two of the reporters, Sean and Bobby, have Down's Syndrome. Larry has a condition called Spastic Cerebral Palsy. The two most talkative reporters, Ron, who has Cerebral Palsy, and Sue, who has a mental disability, came into a studio to talk about the film. They brought along a guitarist, Chad Urmston, one of their counselors, to play some of the songs from the film.

I began by asking Ron what his thing for Chad Everett is all about. It turns out Ron has been a fan ever since he was a kid, back when he was spending a lot of time in and out of hospitals, and Chad Everett was playing a doctor on TV.

Ron Simonsen

My mother and I wrote a letter to Chad Everett. My mother wrote a letter to him, and I dictated. And I named everything he'd been in, not just Medical Center, but everything: The Rousters, Hagen, every show that he was on. And he wrote me a note. He says life's not meant to be on reruns. He said, "God bless your life. Watch The New Love Boat, Chad."

Ira Glass

Watch The New Love Boat? Is Chad Everett on The New Love Boat?

Ron Simonsen

Well, he was a guest on there.

Ira Glass

He was a guest star?

Ron Simonsen

Yeah. Yeah. You know, like I'm a guest star on your show? He was a guest star on that show.

Ira Glass

I see.

Ron Simonsen

Oh, yeah. I want to tell them how we went to the set of General Hospital. Can I tell them that? I went to the set of General Hospital.

Ira Glass

What was that like?

Ron Simonsen

Oh, that was exciting. Wasn't it, Arthur? Want to get in here?

Arthur Bradford

Yeah. That was very exciting. We went to the set of General Hospital when we were in Los Angeles.

Ron Simonsen

And I walked in that studio there, and the guy said, "What the hell are you doing here?" And I said I was a colleague of Monica Quartermaine's, I was a cardiac surgeon. Not really, but it's pretend I was a colleague of hers.

Ira Glass

Right. Did he laugh?

Ron Simonsen

He laughed. He laughed. He thought that was funny.

[LAUGHS]

Ron Simonsen

He thought that was really funny, hilarious, though.

Ira Glass

Yeah.

Arthur Bradford

There's something about, the whole way across the country and then going to General Hospital, when you travel with someone like Ron, who is so excited about certain things, something about his enthusiasm rubs off on everybody else.

So, for instance, going to General Hospital, the set of General Hospital by myself, I'm not sure I would be so excited. But, with Ron, the whole way there, as we got closer and closer to General Hospital, he started clapping his hands and rocking back and forth. And you were just so excited about going to General Hospital.

Ron Simonsen

I was because I wanted to see Leslie Charleson. And we're going to go back there again, in California. Maybe I'll see her again, then.

Ira Glass

Well, let's let Chad come in, and let's have you sing.

Ron Simonsen

All right. Are we ready, Chad?

Chad Urmston

OK, guys.

Susan Harrington

All right. Let's do it.

Arthur Bradford

Ron, and why don't you introduce this session?

Ron Simonsen

This is, today, we're singing my favorite state, California, and where we went to the set of-- to California-- all my celebrity friends. And I'm going to sing it now, for you, Ira.

Ira Glass

All right.

Ron Simonsen

Ready? One, two, three.

[GUITAR MUSIC]

Ron Simonsen And Susan Harrington

[SINGING] You'll never, never know. You'll never, never know. You'll never, never know what you have found. You'll never, never know. You'll never, never know. You'll never, never know what you have found.

Ron Simonsen

[SINGING] California. Oh, California. Oh, California, oh, here I come. I went to the set of General Hospital. I met Leslie, met Leslie Charleson. I got to hold her, her Daytime Emmy, her Daytime Emmy at General Hospital.

Ron Simonsen And Susan Harrington

[SINGING] California, California. Oh, California, oh, here I go. California, California, oh, California oh, here I go.

Susan Harrington

Hi. My name-- oh. Hi. My-- oh. Hi. My name is Susan Harrington. Hi. Hi, would you like to be interviewed? Hi, can I interview you for How's Your News?

Ira Glass

Hey, Sue?

Susan Harrington

Yes?

Ira Glass

I've often been in the situation where I have to walk up to a stranger on the street with a microphone and a tape recorder, and I always get a little nervous. Do you get nervous?

Susan Harrington

Well, you can't do something like this and not have a little bit of nerves and butterflies in the stomach. Come on!

Ira Glass

Do you find that it's hard, sometimes, getting people to talk to you?

Susan Harrington

Yes. Sometimes it is hard because there are people who just will not talk to us. They're like, no way.

Arthur Bradford

When we were at the camp, I think we chose the reporters for How's Your News especially because they seemed to be especially undaunted about going up to strangers and talking to them. In fact, if you were to see Sue in a crowd without a microphone, she just likes to go up to strangers and talk to them.

Susan Harrington

Like, a perfect example is, in the film, the [? assembly ?], and I'm interviewing this Mr. John B. Porterfield. And he was very difficult to talk to.

Ira Glass

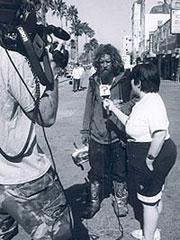

I should say, that interview happens in an alley in, what looks like, the kind of sketchy part of town, and Sue is visibly a little nervous.

Susan Harrington

Sir, good evening. Susan Harrington from How's Your News? And we'd just like to ask you a few questions tonight.

John B. Porterfield

OK.

Susan Harrington

Sir, what is your name?

John B. Porterfield

John B. Porterfield. I am a combat war hero, and I'm living on the streets like a dog.

Ira Glass

Are there times, Arthur, where you're looking through the camera at a moment like that, where you feel scared for them?

Arthur Bradford

Yeah. There were a lot of times when I'm sitting there watching and I'm thinking that I don't want anything to go wrong. I feel very protective. I was always worried about the explosion where someone would just be like, "What the hell are you doing here? I don't want to talk to this person." And so, in that particular interview, I was a little nervous.

Susan Harrington

What I'm asking you is, I'm from out of state, so is there anything you-- I mean, do you think there's anything we should see here that you've seen and you've liked?

John B. Porterfield

I don't like this town. I'm going to tell you that right now. I've been beat up. I've been-- ah, I just want to forget it.

Ira Glass

Arthur, there are a lot of moments in the film where it seems like the reporters are standing there, and they're not exactly sure what to say next or what to ask next. Why not give them questions?

Arthur Bradford

Well, we tried that. We tried making lists of questions for them to ask, and it just didn't work. It was so clear that they were just asking questions that had been given to them that there wasn't really anything very interesting about it. In fact, it came off as a little bit wrong, you know? I think everyone always asks about are you worried about this coming across as exploitation? And, of course. Of course I am. And we all were, so we had to figure out what was and what wasn't appropriate. And, ultimately, I really felt strongly that the questions needed to be coming from them.

Ron Simonsen

My name is Ronnie Simonsen. I'm from How Is Your News.

Ira Glass

This is a guy, he's sitting on a truck. It's about halfway across the country.

Ron Simonsen

Who's your favorite singer?

Man

I like Boston.

Ron Simonsen

What does it say? Please Come to Boston? Is that the name of the song?

Man

Yeah, I believe that one of them is it.

Ron Simonsen

Yeah, you want me to sing it with you?

Man

Huh?

Ron Simonsen

Want me to sing it with you?

Man

No. I don't--

Ron Simonsen

[SINGING] Please come to Boston in the springtime. La, la--

Ira Glass

So, Ron, you do such a nice job with this guy. You know, it doesn't seem like he's all that interested in talking, and then you find stuff to talk to him about where it seems like he actually cares about it.

Ron Simonsen

Well, yeah, I had to do something to make him happy and to make me happy. I couldn't just sit there and say, "Hey, sorry pal."

Ron Simonsen

Can you sing?

Man

No, I can't sing.

Ron Simonsen

Can you act?

Man

No.

Ron Simonsen

Oh. What can you do? What do you like to do? You must have some hobby you like to do.

Man

Yeah. I like to ride a motorcycle.

Ron Simonsen

Yeah? What does it make you feel like when you ride a motorcycle? Does it make you feel like The Fonz?

Man

Yeah, sort of.

Ron Simonsen

Do you like The Fonz?

Man

Yeah, do you?

Ron Simonsen

Yeah. Want me to do an impersonation with The Fonz? I could act it out with you, pretend we're driving a motorcycle. Not really, but just role-play. I am The Fonz. I'm riding a motorcycle. Want to ride a motorcycle with me?

Man

Yeah, might as well.

Ron Simonsen

Come on. Come. Vroom! Vroom! Vroom! Vroom! Vroom!

Ira Glass

You all bring out a really nice side of people.

Ron Simonsen

Well, yeah. Yeah. It all depends on the people.

Man

Where are you from?

Ron Simonsen

New Hampshire.

Man

New Hampshire?

Ron Simonsen

Yeah. We're traveling across country. We're going to California.

Man

Oh. You like doing that?

Ron Simonsen

Sure. It's my biggest dream. What's your biggest dream?

Man

I don't know.

Ron Simonsen

You must have something. You can't have anything if you don't have anything, right?

Man

Yeah. I ain't never thought too much about it.

Ira Glass

One of the facts of life for many disabled adults is that they don't get around that much. Many live in group homes. Most of their contact is with other disabled people. They don't go around talking to able-bodied strangers. For most of the How's Your News? team, this was going to be the first time traveling across the country. This was their first time traveling without their families so far from home for so long.

And in the months since the film was finished and shown on television, the whole How's Your News? team has flown to Europe, and Canada, and around the United States when the film has been screened at film festivals. At those screenings, they bring a band. They perform their songs live, on stage, and it pretty much brings the house down. People love them.

In interviews with Sue and Ron, I kept asking them what all of this was like, how their lives had changed. I have to say, every time that I asked those, they were pretty nonchalant about it all, very low-key. Here's Ron, for instance.

Ron Simonsen

Well, it's good. It's very good, and I felt really honored and blessed.

Ira Glass

In a separate interview with Arthur, I asked him about their reactions to these kinds of questions.

Arthur Bradford

Yeah. It's funny because Ron, who is so celebrity obsessed, often gets asked how does it feel to be a celebrity now? And he just brushes that question off. You know, they've lived their lives. They're all 35, 40. I don't think that this process is going to actually radically change them.

For some reason it seems like they just always expected that this would happen, that someone would pick them up and drive them across the country to make a movie.

Ira Glass

Wow.

Arthur Bradford

I don't know. That sounds weird. But if you ask them, they're all kind of like, yeah, this is the way it was supposed to be. And they took it all in stride.

I think, as filmmakers and American TV viewers, we want there to be this big Olympic moment where they're just like, ta da! I feel so great and my life is so changed. And I do think that they had a wonderful time on this trip but, they didn't-- and I actually like it-- they didn't freak out and start weeping on camera or anything like that.

Ira Glass

What you're making me realize is that my instinct in asking you, even this particular set of questions about this, is suddenly seeming very wrong.

Arthur Bradford

Well, I just didn't want this to be one of those disability documentaries where the music starts soaring, and everybody without a disability feels so good because they have helped these people.

Ira Glass

By understanding them.

Arthur Bradford

Right. The final scene in the movie is we all go swimming at the beach in the Pacific Ocean, in Venice Beach in California. And I do think there's a certain beauty to that. And they were just kind of whooping it up. And, honestly, when we were swimming in that beach, we were all there. We had made it across the country. We were exhausted, but there was a real feeling of accomplishment. The sun was setting, and I really felt this feeling of yes, we have done something here. We set out to do it. We made it across the country.

Ira Glass

I have to say I have to stop you there because I feel like we're getting to that big moment that you tried to avoid in the film.

[LAUGHTER]

Arthur Bradford

Yeah, I know. I guess that's true.

Ira Glass

Arthur Bradford, with Sue Harrington and Ron Simonsen from How's Your News? The movie aired on Cinemax and at film festivals. You can order your own DVD of the film at howsyournews.com.

Susan Harrington

Chad, here we go.

[SNAPS FINGERS]

Susan Harrington

One, two, three.

[MUSIC - "THE GRAND CANYON" BY SUSAN HARRINGTON]

[GUITAR MUSIC]

Susan Harrington

[SINGING] The Grand Canyon was carved by the Colorado River. I learned this in history class. This is really an amazing thing because we are about to dig some history of our own as we have arrived at one of the seven wonders of the world. Beautiful. Beautiful. Beautiful. Beautiful. Beautiful. Beautiful. Take me there. How grand is this canyon? So deep and so wide. How grand is this canyon? So deep and so wide. How grand is this canyon?

Ira Glass

Coming up, yet another three-year-old fan of physicist, Stephen Hawking. And Vinny drops out: assembly line not required. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International when our program continues.

With This American Life, I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose some theme, bring you a variety of different kinds of stories on that topic. Today's program, Special Ed, stories of developmentally disabled people. We have arrived at Act Two of our show.

Act Two: Black Hole Son

Ira Glass

Act Two: Black Hole Son. Because of a very rare genetic disease, Sam was born with holes in several vital organs, including his heart and his brain. For his first five years, if one wasn't making his life hell, the other was. He's seven now. And recently his mom and he sat down together to talk about how things used to be and how they got much, much better.

Sam's Mother

OK. So let me start interviewing you.

Sam

All right.

Sam's Mother

Can you describe yourself? What kind of a person are you?

Sam

I'm nice and kindful person.

Sam's Mother

You're kindful?

Sam

Yes, and playful.

Sam's Mother

What do you do that's nice?

Sam

Hug you.

Sam's Mother

When I was pregnant with Sam, the first ultrasound came back that there was something wrong. I was thinking just please, let it be something with his body not with his brain. I can handle his body, but I'll be a bad mom to a retarded child. Everybody has their thing they can't take, and that's it for me.

So when Sam was born, when he was five days old, he had heart failure. So then we learned about the deletion in the chromosome, velo-cardio-facial syndrome. So we didn't know if he was going to make it. And we had a talk with the geneticist. And he said if you give him the operations, it's not sure he'll pull through. But if he does, he's going to be retarded, probably. And I said OK. I don't care anymore. I want him, and I need him.

Sam's Mother

What were you like when you were three years old?

Sam

I was walking, but I was crying too.

Sam's Mother

Do you want to talk about what you used to be like?

Sam

No way.

Sam's Mother

He started torturing animals when he was three, and talking all the time about wanting to die. And he stabbed his stepfather with a plastic knife and drew blood, and poured boiling water on me, wiped things on the bus that should not be wiped.

He was kicked out of school when he was four because they said he was a danger to himself and others. And so we took him to a psych unit, and he was studied for a few days. And that's when they told us about the bipolar, rapid-cycling bipolar, which is common in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. It has early-onset, and it hits you hard a lot of the time. And sometimes it doesn't, but it did in him. But nobody told me that.

Sam's Mother

I want to show you a drawing that you did.

Sam

That's me with heart faces and heart eyes.

Sam's Mother

There's about 100 hearts in your face in this drawing.

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

Green hearts, how come? What were you feeling when you drew this?

Sam

I was feeling like hugging you and kissing you and giving you cards.

Sam's Mother

All your drawings now have a lot of hearts and flowers and birds, and people are smiling. Do you remember, when you were about four years old, do you remember what you drew all the time?

Sam

What?

Sam's Mother

Black holes?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

Do you know what you were feeling when you were drawing black holes every day?

Sam

Like, the black hole was going to suck the whole world up and make everybody die and end of the world.

Sam's Mother

Yeah. Did you feel like that a lot, like everybody was going to die?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

I think the first time Sam heard of a black hole, he was almost four. And we were watching Stephen Hawking, a show. At that time, he couldn't sit down for anything. He couldn't sit down for a 15-minute cartoon. But he was really into space. And this was the only time he sat down and he watched the boring show from start to finish. They had, I think it was like a '50s cartoon of a black hole on just for a second, you know, one of those swirly things. That just captivated him. He started drawing it all the time. In every family portrait, it'd be us and the black hole.

At school, they had this rainbow bear notebook and it would have all the kids' drawings in there. And there would be, like, 19 drawings of kids going sledding, kids going to McDonald's, kids playing with their siblings or something. And then, on Sam's page, it would be a black hole destroying the universe or a black hole coming down the railroad tracks sucking up humans. I was kind of proud of his differentness and his imagination, but, at the same time, I knew that it was like this horror to him.

Sam's Mother

What are some nightmares you've had?

Sam

The moon, blowing moon.

Sam's Mother

The moon blows on you?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

How come?

Sam

I think of bad thoughts that time. I mean, bad thoughts.

Sam's Mother

You had bad thoughts and that's why the moon blew on you?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

Did the moon know you had bad thoughts?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

What would happen when the moon blew on you?

Sam

I was scared and frightening.

Sam's Mother

And you had that nightmare a lot, I think.

Sam

Two times.

Sam's Mother

No. Like a whole year you had that nightmare.

Before he discovered black holes, it was any swirling thing that sucks you in. Like, even when he was months old, if he saw a ceiling fan, it was the only time he would quiet. He would just stare at that ceiling fan. I know a lot of babies do, but he just was obsessed.

And then, when he was three, he had an imaginary friend, but it wasn't a boy, it was a fan. But this one was called bad, bad fan. And its blades were teeth. And then it had these little, tiny eyes and these little, tiny feet at the bottom, and it would kill people. It would just blow on people and that would kill them because his breath was filled with teeth. And then, sometimes when he broke things, he said bad, bad fan did it. And it was kind of creepy, you know? It was just me and him living in the house. And you start thinking-- oh.

He had to destroy all day long. He had to. He couldn't not. He destroyed his favorite toys. He destroyed my favorite furniture, anything that meant anything, especially.

And I used to watch The Sally Jessy Raphael Shows, or whoever it was that had all those shows about the out-of-control-- I think it was Montel-- had all the shows about the out-of-control, really young children. And the parents had to lock the door against them at night. And they lived in fear. And, supposedly, nobody could help.

And I would always think well, you must be really bad parents. I would never have a problem with controlling my kid. I would teach them how to act. And if I had your kid for a week, he'd shape up. And so, of course, once I became afraid of my child, I didn't tell anyone because I thought they would think the same thing about me. And I kind of thought the same thing about me. You know, he'd be nice and normal, and then just do something so horrible and senseless.

And it seemed like that to Sam too. He could never understand. He'd do something like try to break the cat's leg, something like that. And then, immediately afterwards, he'd be crying and saying, "I don't know why I did that." And he would be just as angry and sad as I was. And he'd say, "I don't understand." And he'd start punching himself and biting himself and putting bruises all over his body. Ugh! Oh, that was a horrible life.

Sam's Mother

Do you know why you take the pills every day?

Sam

Because my brain is all, like that.

Sam's Mother

What is that? Nobody can see on the recorder. Describe it.

Sam

It's so wild. And has to-- it's pumping blood all wild.

Sam's Mother

Pumping blood all wild?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

He started on a drug called Zyprexa. And within 24 hours we noticed a change. And then, after about 56 hours, it was like night and day. This was not the same kid at all. It's hard to believe that we were all living like we were. I mean, I can't believe it. When I sit here and talk about it, I can't believe that that existed and I didn't try to get a diagnosis earlier. I just kept on thinking I could not be such a bad parent and it would get cured. Or, I don't know what I thought.

But, within two days after starting on the Zyprexa, we would go out. We could go to do three errands in one day. He could wait in line. He was doing well in school. I mean, it didn't happen overnight because he still at some bad memories, but he started to get some nice memories to put on top of the bad ones. And he just got nicer and nicer, and happier and sweeter. He stopped having nightmares. At first, he would ask me when his brain was going to be messed up again, but now he feels like it's his brain, you know? He feels like he's in control of his own brain.

Sam's Mother

Do you have any girlfriends?

Sam

Yeah, only one. Who is it? Rose.

Sam's Mother

Aw. Tell me about Rose.

Sam

She's kind and cute.

Sam's Mother

What does she look like?

Sam

I forget.

Sam's Mother

[LAUGHS]

Sam

She looks kind of like her mom, maybe.

Sam's Mother

Would you like to be married?

Sam

Yeah! I would like to be.

Sam's Mother

What is marrying like?

Sam

You have a bride. And you are giving them flowers and heart and Valentines stuff.

Sam's Mother

When I was doing these interviews with him, I realized something about him that I hadn't seen before, which is all those hearts and bunnies and rainbows that he talks about all the time, it's not because he's silly. It's because he's been through more pain and powerlessness than most people ever will in their whole life. And I think he took all that information about life, about what it is, what it means for him to be alive, and he made an informed decision that he's going to be happy with the good parts of life and he's going to spread them around. And I think he knows something about hearts and bunnies and rainbows. He's not like Forrest Gump, you know? It's not like-- you know, he came out of something very hard, and he has a very strong will.

Sam's Mother

Let's make up a story about a bad boy.

Sam

[UNINTELLIGIBLE] boy?

Sam's Mother

Sure.

Sam

No. That'd scare people out.

Sam's Mother

That would scare people listening?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

Let's make up a story about a human boy. What would he do in the day?

Sam

He would just have fits. And then he would [UNINTELLIGIBLE] his bowl, and then he would spill it, like that.

Sam's Mother

Push his bowl of food away and spill it?

Sam

Yeah.

Sam's Mother

What else?

Sam

Break the bowl. And his mom will say, "You have to clean it up. And, after that, you will have to go right up to your room."

Sam's Mother

What would the boy be thinking?

Sam

That he wants to be a nice boy. Then when he came back downstairs, he hugged everyone in the world. The end.

Sam

Wow. That bad boy turned out to be a good boy. Do you know anyone like that?

Sam

No. It's fake.

Ira Glass

The mother who put that story together asked that we not broadcast her and her son's name.

[MUSIC - "KEEP THE SUNNY SIDE" BY THE WHITES]

Act Three: Walkout

Ira Glass

Act Three, Walkout. Sun Kim has taught severely autistic children for the past five years. She says autistic kids, in general, tend to not understand social cues, and that her students, because of the severity of their autism, can't tell her their basic needs or thoughts. And so she finds she spends a lot of her work day trying to figure out what it is that they're thinking. And often, she's stumped.

Sun Kim

Sometimes you'll just see them looking off in the distance and laughing. You think what are they laughing about? What's so funny? Or when we ask them to do certain things, like pass out the place mats or pass out the cups, what's going through their head process? Like, OK, I'm supposed to do this and I don't-- or are they hearing just, murmur, murmur, verbiage, and not really understanding? Or just listening to the tonalities of what we're saying? Believe me, I've wanted to be inside their head just to know what they're thinking or feeling so many times.

Ira Glass

This question, of course, was part of our story in Act Two. And it's at the heart of this next story. It's at the center of what it means to deal with certain kinds of people with developmental disabilities.

Veronica Chater's younger brother, Vincent, can't do math, even the simplest addition. He doesn't speak well. He has a version of what used to be called mental retardation. But, when he was a baby and doctors tried to diagnose him, they couldn't find anyone else with his particular combination of symptoms, and so they named his own syndrome after him: the Vincent syndrome.

He's an adult now. And for a while seemed to be doing just fine, until a point a few years ago when he surprised everybody in the family by quitting his job, and then quitting everything else in his life. And it was not clear to them why he did it and what it meant and what it would mean for his future. Veronica Chater put together this story.

Veronica Chater

Ever since Vincent quit his job, he spent more and more time alone in his room. At Christmas, at our parent's house in northern California, my brothers and sisters and I weave in and out of the kitchen, talking about work, telling jokes, and taking orders from Mom.

There are 11 of us. I'm the second oldest. Vinnie's the fifth. As usual, he's nowhere to be seen. When I go down the hall, I find him in his bedroom with the door closed, drinking an orange soda from the can and watching an old movie.

[SOUND OF TELEVISION]

His face is close to the TV screen, about 10 inches away. And he has a serious expression, the kind you catch on a detective who's trying to crack a case. He could be 18 and he could be 50, you can't quite tell. He has a short little boy haircut. And, every day, he wears a sweatshirt with the words carpe diem on it. The truth is, he's 34.

Veronica Chater

Did Santa come and fill your stocking?

Vincent

Indeed.

Veronica Chater

What did you get in your stocking?

Vincent

[UNINTELLIGIBLE]. Jamaroonie.

Veronica Chater

Some jamaroonies?

Vinnie still lives in his childhood bedroom, which he calls his apartment. Ever since he retired, bit by bit, he's been withdrawing into his own little world, a world that doesn't include me or anyone else.

Vincent's Mom

OK, here we go. Cleaning up.

Veronica Chater

My mom and dad still take care of Vinnie, but it's mainly my mom's job.

Vincent

Clean it, clean you.

Vincent's Mom

Well, we'll shave you, shave you.

Veronica Chater

My parents, who are devout Roman Catholics, were undaunted by the idea of having a, so-called, special needs child. They figured it was part of God's plan. He was an angel in our midst, as my dad always said. They refused to think of him as a burden, even though he would depend on them for the rest of their lives. Every morning, my mom readies him for the day: combing and gelling his hair, brushing his teeth, and shaving him.

Vincent's Mom

[SINGING] I like my clean-shaven man.

Veronica Chater

She tilts his chin this way and that, handling him like a barber with an overbooked schedule.

Vincent's Mom

Done. All spiffed up for the day. OK, here.

Vincent

Here we go.

Vincent's Mom

Put your shaver away, OK?

Veronica Chater

There are all sorts of little games that Vinnie and my mom play together all day long. Most of them are impenetrable to outsiders. He'll say, "Repeat. Repeat." And she'll reply, "Redeep in the redeep." And they'll both giggle.

Vincent's Mom

OK, so I'm going to test you. I want to see if you know any movies because you're always the one that knows movies. OK. Who said this? Who's the one that sucked his thumb and said, "Mommy"?

Vincent

The cartoon Robin Hood.

Vincent's Mom

Right. You got that one. I didn't know if you were going to get that.

Veronica Chater

Despite his disability, Vinnie has a really good memory for all sorts of trivia. Quizzing him about movies is the impromptu game my mom and dad play with him throughout the day, from morning till night.

Vincent's Dad

OK, I've got one for you, Vincent. See if you can get this one. [SINGING] It was a Monday. Ain't gonna soldier no more.

Veronica Chater

The bond between them is more than a bond, it's a union for life. As Vinnie passed through his teenage years and became an adult, Mom saw to it that he was kept busy. She signed him up for bowling, for Special Olympics, and for pretty much every seasonal sport from basketball to badminton.

But as he got older, Vinnie's personality grew darker and more mysterious. I didn't notice it right away. I don't think any of us did. Mom was so good at keeping Vinnie distracted from himself that it didn't seem like a problem. But two years ago, it grew too large to ignore.

Vincent

Let's play games.

Vincent's Mom

I'm not playing games right now. Go get my sour cream. Come on. I want the sour cream. I can't make those chantilly potatoes without it.

Veronica Chater

Every time I go home, it hits me a little bit more that, even though Vincent and I are about the same age, my mom talks to him like he's a precocious four-year-old. And, more and more, I've noticed that he's aware of it too. When he returned without the sour cream and noticed that Mom and I were talking about him, he got upset.

Vincent

It is a wonderful reaction to talk about somebody? When you talk about me, I wonder.

Vincent's Mom

I talked right in front of you. I wasn't telling any secrets. I'm going to say what I'm going to say because it's true. There's nothing wrong with having the truth, is there?

Vincent

I'll put this away here--

Vincent's Mom

You know, where it goes. Top shelf. The little slot, slide it in there. Thank you, very much.

Vincent

No.

Vincent's Mom

He can go from one minute to-- oh, yeah. Dad's so afraid he's going to get him angry, he won't give him any orders. I have to give all the orders. Yeah. If he wants to get smart with me, and I say, "God said you have to obey your parents I'm your mother. You do what I say, when I say. Da, da, da, da, da. Da, da, da, da." And he'll do something, sometimes I say, "You go in and you tell God you're sorry for that." He'll go in his room. And he comes out, "Sorry for talking like that." And I said, "That's fine, Vin. OK. We just don't do that." Then he gets in a really good mood after that.

Veronica Chater

It might seem like my mom is rough on Vinnie, but I have to say that her way of dealing with him has pretty much worked out for the best, until the day Vinnie decided to retire. When he quit his job, Vinnie dropped everything including bowling, basketball, and the Special Olympics. Where once he was busy from dawn till dusk, now he had nothing to do, so he began sleeping to pass the time, up to 18 hours a day. It worried all of us, especially Mom. He was sleeping his life away, and we didn't understand why. It felt like we were losing him, like he was giving up, so I set out to figure out why.

If you ask Vinnie about why he quit his job, you don't get much of an answer. In general, it's hard to get a direct response out of him on any subject. "Could be," he'll say, or, "Maybe." It's not clear he even knows what his own feelings are sometimes. Often, when any of us asks him about his job, he'll just change the subject, like he did when I asked him about it, sitting in Mom's kitchen.

Veronica Chater

How come you don't just tell me why you quit?

Vincent

But seriously, it might be empty, blank there, after you were saying something.

Veronica Chater

You mean you're leaving that section blank because you don't want to fill it in with words?

Vincent

Blank is there before I finish words.

Veronica Chater

Are you playing word games with me now?

Vincent

No.

Veronica Chater

We've all asked Vinnie dozens of times in dozens of different ways why he quit his job and everything else. And every time his answer is just as cryptic, and so we're all forced to guess what the real reasons are. My mom's best guess is that Vinnie put himself into early retirement and started all these dark moods because of a chemical change in his brain.

Vincent's Mom

The psychologist said he thinks there was a chemical imbalance that took place, suddenly, in his brain. And he prescribed Prozac for him.

Veronica Chater

Well, it's all chemical.

Vincent's Mom

I don't know. It's really a mystery to me what happened there.

Veronica Chater

Vinnie had worked for 12 years at a place called Concord Support Services, a company that hires mentally retarded adults and vocationally trains them. Vinnie always told me that he liked his job. He'd sit in a big warehouse with about 70 other disabled adults doing light assembly or stuffing envelopes. He made up to $60 a month, which, to him, was an infinite amount of money. We all assumed he'd found his place in the world.

Then, gradually, he started to become impatient and angry at work, threatening to break people's fingers if they touched him. He started disappearing into the work bathroom for up to an hour at a time just to get away from people. It was pretty clear that he was in a crisis.

On his last day, he was wandering around looking for a bead he'd dropped. His supervisor asked him what he was doing. One thing led to another. Vinnie lost his temper. My parents were called in for a meeting. And Vinnie quit, just up and walked out.

A few months ago, I asked Vinnie if he'd like to go back to his old job for a visit hoping it might spark something. I wasn't sure how he'd react, but he didn't even hesitate. He told me that he'd love to go. So the next morning, after my mom spiffed him up, we drove the route he'd taken for 12 years. When we arrived at the front doors, he's all smiles. He seems genuinely glad to be there.

Vincent

Hi.

Woman

I remember you.

Vincent

You do? Nice to see you.

Veronica Chater

But, as we approach the warehouse floor where Vinnie used to work, his pace slows. At the warehouse door, he hesitates and purses his lips together.

Vincent

Hi.

Man

How are you?

Vincent

Wonderful. Hi. Nice to see you [? Jane. ?]

Woman

Nice seeing you.

Veronica Chater

He becomes shy and looks confused as one person after another comes up to him. Some touch him fondly, one man blows in his face, and everyone stares. Vinnie tries to appear cool, but I can tell he's tense.

Man

We miss you, Vinnie. We miss the Vinnie Arnold we knew. We missed you, Vinnie. We missed you.

Vincent

Would you like to begin basketball practice Saturday?

Man

I don't know. I'm not into-- I'm back into bowling and running again.

Veronica Chater

We hang out. And Vinnie looks uncomfortable, except when he decides, on his own, to busy himself cleaning and straightening. After 15 minutes, he disappears into the bathroom, his old hiding place. After a while, he comes out for a few minutes, then goes back in, and then comes back out again. When he heads back into the bathroom for the third time, I know it's time to leave.

Later, I talked to my brother, Danny, about it. Of all my siblings, Danny spends the most time with Vinnie. They go to movies, take walks, go to bookstores. Danny thinks Vinnie might have quit his job for all the normal reasons any of us quit a job. Maybe it had nothing to do with his disability.

Danny

I think he was probably extremely bored working in this place, doing the same thing over and over again: stuffing envelopes, putting paper clips in bags. There was no challenge to it, and I think it really frustrated him.

Veronica Chater

Vinnie might have simply had enough, enough of other people controlling his life. All the adults in his life were doing the sensible things you do for disabled people: giving structure to his days, coaxing his moods, all with the best intentions. It's possible that, in the end, that wasn't enough of a life. And so, one day, he changed the one thing in his life that he could. He said no to the one thing he could say no to and quit his job, and then quit everything else.

Danny

Being told what to do constantly, day in, and day out. And then he watches his other brothers and sisters running around and traveling and having their freedom, and here he is, stuck at home in his room. I can just imagine how frustrating that would be. It would make me angry if I was in that situation.

Veronica Chater

After Vinnie retired, my mom and dad were determined to get him back into some kind of routine. After meeting with all sorts of social workers and suggesting dozens of ideas to Vinnie, they finally came up with something that he agreed to. They hired my brother, Bernard, to build a chicken coop in the backyard and to put Vinnie in charge of a miniature chicken farm. My mom had always wanted a chicken farm anyway. This was her big chance to get one.

Vinnie took to every aspect of chicken farming. He was painstakingly mindful of the chicken's daily schedule of free-range feeding and lock-up. And he was especially fastidious about coop hygiene. But more than that, to everyone's surprise, he started participating in activities again. He started basketball practice. And he's training again for the Special Olympics.

Vincent

Molly, Polly, Jeanette, and Lonnie, here.

[CHICKEN CACKLE]

Veronica Chater

Pretty much at any time of the day, you can see Vinnie standing as still as a marble sculpture in the backyard beside the coop, his eyes half closed, and his palms cupping the breeze, thinking, or just listening to the sound of his hens. He named them after old friends and talks to them like children.

[CHICKEN CACKLE]

Vincent

Molly, Polly, Jeanette and Lonnie.

[CHICKEN CACKLES]

Ira Glass

Veronica Chater lives in Berkeley, California. She has a memoir coming out about her family next spring called, Waiting for the Apocalypse.

[MUSIC - "9 TO 5" BY HAMMOND STATE SCHOOL PERFORMING GROUP]

This cover of 9 to 5 was recorded in 1985. It's the Hammond State School Performing Group in Louisiana. They are developmentally disabled kids in a music therapy program.

Our show today was produced by Jonathan Goldstein and myself with Alex Blumberg, Wendy Dorr and Starlee Kine. Senior Producer is Julie Snyder. Production help from Todd Bachmann and Maria Schell.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

Our website, www.thisamericanlife.org, where you can get our free weekly podcast or listen to old shows online, for free. This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

WBEZ management oversight for our program by Mr. Torey Malatia, who has this message for America.

Ron Simonsen

God bless your life. Watch The New Love Boat.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

Announcer

PRI. Public Radio International.