327: By Proxy

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

There's really no way around some arguments. Maybe arguments just want to happen. One of the producers of our radio show, This American Life, was at this conference recently, and this guy named Eric Molinsky told her about this strangely and unexpectedly fierce argument that he had gotten into with a good friend of his. It was his cousin in fact. And the whole thing started with no warning at all. Like he told Nancy, they were happily chatting away in a nice warm cafe.

Eric Molinsky

Everything was like comfort food, comfort seats and we were so comfortable--.

Nancy Updike

I'm getting tense already just hearing about it.

Eric Molinsky

We were so comfortable. It was one of those things where you actually could hardly touch the table. You actually had to sit up in your giant lounge chair to get the soup on the little table.

Nancy Updike

The comfy soup.

Eric Molinsky

The comfy soup, yeah. So we were talking along, and I remember I-- somehow I brought this up, about corporate tax loopholes. And then she was like, first she said, well, let me play the devil's advocate here. Not that I'm defending corporations, but don't you think that if you're going to make them pay taxes, they're just going to pick up and leave and go to another state? And she kept saying, not that I'm defending corporations.

And we kind of got deeper and deeper into this, and she sort of eventually stopped apologizing for defending corporations and really was going after this idea that it was just irresponsible. It was typical kind of liberal--.

Nancy Updike

Knee jerk.

Eric Molinsky

Knee jerk.

Nancy Updike

Anti-business.

Eric Molinsky

Exactly And this is the way the world works. This is the way the world goes around. Money, money, money. I ended up being grandstanding. This goes into the highways, this goes into health care for everybody.

Ira Glass

And in the middle of this tirade, in the back of his mind, Eric was thinking, why are we getting so heated up over this, both of us? And then, something occurred to Eric.

Eric Molinsky

I think the way that I said it was, you know, I have to admit, I really don't know a lot about this issue. Or I didn't really know a lot about it until my ex-girlfriend explained it to me.

Nancy Updike

When you said that, what did your cousin say?

Eric Molinsky

Well, she paused. And she said, well, to be honest, I didn't really know a lot about this issue either. But I had an ex-boyfriend who educated me on it.

Ira Glass

Eric's ex-girlfriend was a political activist with a special focus on corporate tax loopholes. His cousin Mara's ex-boyfriend worked in hedge funds.

Eric Molinsky

And so we just stopped for a second. And it was interesting, because that was the end of the argument and that's when I said to her, I think that my ex-girlfriend just got into a huge, 20-minute argument with your ex-boyfriend.

Ira Glass

You know when you fall in love with somebody, it's like they have an open path straight to your heart. And without you even realizing it, other things can just ride in on that path-- political ideas, favorite bands, favorite writers, pet peeves. And where those things are concerned, you basically just become the person you love. You're like their proxy. In my own life, my own opinions about television are so thoroughly shaped by my wife's opinions that a coworker recently told me that sometimes she wished that she could just skip the middleman and talk straight to my wife.

But I think that we don't just become proxies for the people that we love. It happens with friends. It happens in business settings. It happens in politics. And when it happens, things can get very confusing. When you really step in for somebody else, substitute yourself for somebody else, it can be hard to tell if you're doing the right thing at all. If you're doing what they would want or what you want.

Well, from Chicago Public Radio, it's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass. Today's show, By Proxy, stories of people turning into proxies for other people, sometimes by choice, sometimes they just find that it's happened to them without them even noticing. Act one of our show today, I'm The Decider. What do you do when a friend asks you to make a decision that she probably should be making for herself? Well, Davy Rothbart found himself in that very position. Act two, Killing The Messengers, what it's like to be the proxy for the least popular guys in town, when the town is Mosul and the guys are the US Army. Act three, Redemption By Proxy, a teenage girl and a message from beyond the grave. Stay with us.

Act One: I'm The Decider

Ira Glass

Act one, I'm The Decider. There are all kinds of situations where we step in as reluctant proxies. As a favor for friends or family, taking over some chore they don't want to do, taking their kids or their pets off their hands for a while. Doing something because it's the right thing to do and nobody else is stepping in. That's what happened to Davy Rothbart, more or less.

Davy Rothbart

So Cassandra is this childhood friend of mine who moved away when she was maybe 13 to Chicago, then to California, then Pensacola, Florida. I think she had kind of a tough go of things growing up. She never really knew her dad, and her and her mom and brother kept moving around a ton. A couple times she called me crying when she had to pull up stakes again. We wrote a lot of letters back and forth, and when we were 20, we traveled around Eastern Europe together, just as friends.

Every couple of years since, she'll surface in my life by way of a middle of the night phone call. She'll be in the midst of a crisis and desperate for my advice. Maybe about problems at her work, or with school, or with a boyfriend, her little brother in trouble with the law. She'll say things to me like, you're so sensible. You understand how things work. You're so smart about things. Not just smart, but wise. It's kind of hard to resist.

So after she calls me with a problem, for a week or so we talk every day, just going through it all. And by then, we've figured out a good approach. Say she's got a manager at work who's overly flirtatious, making her uncomfortable. I kind of ask her a bunch of questions. What's he doing exactly? How often? Have other people witnessed his behavior? Who's his supervisor? After talking a bunch, we make a plan for some kind of decisive action. She feels a whole lot better, and I, in turn, feel sensible, knowledgeable and smart. Not just smart, but wise.

Then a few years ago she called me, freaking out. She had a new kind of crisis, not like anything I had ever dealt with before. She was pregnant, almost three months pregnant. The dad was her sometimes boyfriend, a hippie wanderer type named Rainbow Bear. She was living in Santa Barbara, she said, without any close friends around, no one to really turn to, and she was really upset and confused, torn up about whether she should have this baby or not. Rainbow Bear wasn't involved. She said to me, tell me what to do and I'll do it.

So I did pretty much what any sensible and smart person would do in that situation. I told her I couldn't make the decision for her, but that I would do everything I could to equip her with as much information as possible, so that she'd be able to decide what to do on her own. Then I got to work. I knew one friend who'd had an abortion and had always been haunted by it, and another friend who'd had an abortion and, while sad about it of course, really believed it had been the right thing to do. I also found a woman who'd given her baby up for adoption, and another who'd kept her baby and was a single mom.

I got them all to agree to talk to Cassandra, but she was really shy, and too upset to reach out to strangers. Those are your friends, not mine, she said, I'll feel weird calling them. So OK, I changed my plan, and talked at great length to each of these women myself, then relayed their stories to Cassandra, careful to present them in a balanced way, so it wouldn't seem like I was favoring one option over another.

I'd even gone so far as so talk to a couple of friends in med school to gauge the medical risks of a later first term abortion. Relatively safe, it turns out. At the end of all this, Cassandra was only more confused and overwhelmed. Please, she begged me, tell me what you think I should do. And that's where I should have said, look, nobody can tell you what to do in this situation. Of course this is agonizing, but only you can know what path to take. Whatever you choose, that will be the right decision. But that's not what I said.

Cassandra was barely getting by on her own as a cashier at a health food store. No medical insurance, shady roommates, a shaky lease, a boyfriend named Rainbow Bear. Cassandra, I said, I know being a mother appeals to you but you're still so young. Maybe this isn't the right time. Down the road you'll have the chance to have a baby with a guy who's going to be there to raise the child with you. It's just going to be so hard on your own. I think you should wait. I think you should wait. Sort of a pleasant euphemism for kill the fetus.

Cassandra sounded sad but she said I was right, and that now she knew what to do. She kept thanking me for being such a kind and generous friend. We talked maybe once more the next day, and then she disappeared again. For months afterwards, I felt weird about what I'd done. I did think it was probably for the best, but what if something went wrong and she was never able to have children again? Or what if she never found the right guy and this had been her one chance to be a mother? I think it would have felt equally weird if I'd told her to have the baby too. I just felt like I shouldn't have been the one to decide.

Three years later, I'm living in Chicago and I get a call. It's Cassandra. She's in the Chicago suburbs staying with her grandfather. She invites me out to visitor her and we agree to meet the next day at the playground across from her grandfather's house. I pull up, hop out of my car, and there's Cassandra, waving to me from beside the swing set. Then I see, tearing through the grass toward me, a little blond, two year old boy. It's Cassandra's son of course. She had the baby after all, and he's got the same name as my favorite basketball player in the world, Isaiah, like Isaiah Thomas. Davy, meet Isaiah Bear.

My eyes got all watery. And Isaiah, he's like the most incredible, joyous, dazzlingly intelligent two year old boy I've ever met in my life. I swear this is true. That night, we brought him to my friend Nicole's house. I was couch surfing at her place at the time. And when we introduced him to 12 people in a circle, he went right back around and knew every single person's name. Incredible. At the same time, as amazing as Isaiah was, Cassandra was struggling. Rainbow bear had rumbled off and she'd been bouncing from town to town, first staying with his parents, then an old boyfriend or two, and now her grandfather. But that was a bad situation too. She had to get out of there.

And here I was. I felt pretty guilty for having pressed Cassandra to have an abortion. Somehow I thought, if I could help his path toward a good life, I could make up for that little part where I'd suggested he be exterminated. So I jumped back in again. I took over. And I came up with a plan. I'd move back home to my folks' house in Michigan for a little while. I'd bring Cassandra and Isaiah to live with us for a couple of months in Ann Arbor. And Cassandra said that's what she wanted. Stay with my folks, get a job, work and save money, then move into her own place and raise her son.

I was really excited about the whole thing. I truly wanted to help Cassandra, you know? She'd been a lifelong friend. And I also liked the idea of being altruistic. And the idea that this other girl I was chasing after at the time might see me as altruistic. And it occurred to me that living with Cassandra and Isaiah would be kind of like having my own kid. At the basketball court where I'd played ball in Chicago, there was this one guy who always brought his two kids with him, like two and four years old. Between games, he'd mess around with them for a couple of minutes, or shout at them from wandering too far away. I liked the idea of showing up at the court in Ann Arbor with Isaiah, and being able to cuff him, roughhouse with him and teach him how to shoot. Being a dad, or acting as a dad, makes you feel more like a man. Makes you seem a little more tough and rugged.

Having Cassandra and Isaiah in Ann Arbor was great. My mom got a little kiddy pool for the backyard, and Sandra and Isaiah spent all afternoon and evening back there. Cassandra made soup and all kinds of complicated vegan foods in the kitchen and washed her clothes with a hose and hung them up to dry on the old, rusty playground equipment out back. We had a basketball hoop in our driveway, and me and my friends started showing young Isaiah how to shoot. We called him Zeke, after Isaiah Thomas' nickname. And the kid, Zeke, had the sunniest disposition, and he was a natural athlete.

I started in pretty quickly trying to find Sandra a job. Between me, my friends, and my parents, we found a few solid leads, solid enough that all she had to do was show up for an interview and the job would be hers. These weren't dream jobs, but they were decent paying jobs, like working the register at a Birkenstock store or taking phone orders at Bell's Pizza. But every time we had an interview set up for Sandra, she managed to miss it. She got lost on her way there or Isaiah was nursing and she couldn't leave him right then, those kinds of things. Finally, one day I drove her to an interview. Though she had her own car, I just wanted to make sure she actually went to it.

She got the job, a receptionist at a new agey type salon. They asked her to start work the next morning. I drew a careful map with clear directions so she'd have no trouble finding the place and even set her alarm clock to wake her in plenty of time to get to work. My plan was for me and my dad to split the day looking after Zeke, and then on days we weren't around, Zeke could go to daycare. But the next morning, I wake up and Cassandra's just laying in bed, playing with Zeke. I charged into the room. Oh my God, you're two hours late for work, and it's your first day. And she's just like, oh, I decided not to go.

If you knew Cassandra, you'd be shocked when I told you that she never smoked pot because she just had that total, glassy, dreamlike air to her, completely unperturbed by real world situations. In a lot of ways, she was like a child, which became so frustrating. Cassandra kept putting all of her decisions in my hands, but then she wasn't actually doing any of the things I was telling her to do. And I finally realized, things that were easy for me, like showing up for work on time, showing up at all, were not easy for her. It was clear, she wasn't going to get a job.

And I don't want to be too critical. Taking care of her two year old, she was exhausted all the time. And really, I began to understand just how difficult it would be to raise a kid on your own. I mean, that stuff is relentless when you have two parents. But all alone, it's brutal. Even for me, the allure of playing dad began to wane. I was stuck babysitting a lot. When I tried to take Zeke with me to the schoolyard where I always played basketball, he didn't understand that he couldn't come out on the court when the grownups were playing, and I had to leave the game and take him home. And most days, I'd be at home, trying to get some kind of important work done on the computer, and play Hungry Hungry Hippo at the same time.

Suddenly, I felt desperately like I needed an out. My parents recognized that Cassandra had no intention of finding her own housing and they were ready to have their house back and I was ready to have my life back. My stab at playing dad revealed itself for what it was all along-- a theme park ride, a novelty, a selfish gift. So naturally, I hatched a new, even more ill-conceived plan, and tried to hook Cassandra up with my friend Brandy, so he could take her off my hands.

I knew Brandy was into Cassandra, and he was great with Isaiah, so I kept making plans for all of us to hang out together, then ducking out at the last minute. Randy took over all the dad responsibilities I'd felt saddled with, and Cassandra enjoyed Brandy's kindness and attention. There was actually a momentary romantic spark, and I saw everything unspooling beautifully. But Randy was living at home with his own mom, and they were barely making ends meet as it was. Randy's mom quashed everything really quick. There's no way they're moving in here with us. One of the lowest moments of this whole strange saga was when Cassandra said to me one day-- not angrily, just plainly-- if you want me to leave, I'll leave. You don't have to try and peddle me off on your friends.

There's a TV show from the '80s that I saw only a handful of times, but always really loved, called Quantum Leap. Remember that? Each week's episode would revolve around a different person caught up in a complicated and difficult situation that they couldn't fix. And the star of the show, Scott Bakula, would actually be zapped into that person's body, become that person, and he would make things right. It's one thing to get involved in other people's problems and do your best to help them. But man, it'd be a whole other thing if you could actually inhabit their body and fix everything up yourself. Then you could really help some people.

I'm sure in the end, it's not the best way to do it. At the very least, it's kind of a bullying way to look at other people's problems. But I guess that's me, wanting the ball in my hands, wanting to run the show.

Not long after Cassandra told me I didn't need to peddle her onto my friends, she decided that she and Zeke would pack up and leave town. She had been talking to Zeke's dad, Rainbow Bear, on the phone, and they were going to try to get back together. Rainbow had moved to Hawaii, and Sandra and Isaiah were headed there to meet up with him. It was one of those things where it seemed clearly kind of sad and hopeless, and at the same time, I didn't want to talk her out of it, because it meant they'd be gone and I could resume my own directionless life.

Cassandra was nothing but sweet and totally appreciative of what me and my family had done for her. But I felt miserable. I worked with little Zeke one last afternoon on his perimeter shooting, then watched him and Cassandra drive away. And then I cried.

Ira Glass

Davy Rothbart in Ann Arbor. His book of stories is The Lone Surfer of Montana, Kansas. He's also the creator of Found Magazine, which is at foundmagazine.com.

[MUSIC - "I DON'T KNOW WHAT I CAN SAVE YOU FROM" BY KINGS OF CONVENIENCE]

Coming up, so your country's been occupied by a foreign army, and you work for that army. Who should you really be loyal to? A guy caught in the middle of that problem in a minute, from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International, when our program continues.

Act Two: Kill The Messengers

Ira Glass

It's This American Life, I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, we choose a theme and bring you a variety of different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's show, By Proxy, stories of people substituting themselves for other people, and the difficulties that can create. We've arrived at act two of our show. Act two, Killing The Messengers. Being a proxy can get you murdered. Basim grew up in Iraq, trainined to be an English interpreter. And when the US Army arrived, he got a chance to try out his language skills on actual native English speakers for the first time in his life. Iraq had been cut off from the world for so long, he says, that generations of English teachers were not able to travel outside the country and speak English. So his English had all kinds of mistakes in it as a result.

But he spoke well enough that the Americans offered him a job as an interpreter, and it was a job that he really loved. He made decent money, and he felt like he was helping rebuild his country and bring it into the modern world. But translating for the US Army meant being a proxy for the Americans when he was talking to Iraqis, and being a proxy for the Iraqis when he was talking to American soldiers, which put him in a lot of tough situations.

A quick example: sometimes Iraqi policemen and police trainees would be standing right next to the Americans and then bad mouth them in Arabic. Basim wouldn't translate what they said. That would just make trouble. Instead, he would warn the police in Arabic that they should watch their mouths. That some translators would, in fact, tell the Americans what they were saying word for word, and there was no predicting how the Americans would react. Sometimes the Iraqi police would reply that Basim was taking the Americans' side. It was their country.

Basim

And we are talking about Iraqi policemen. They were an authority in Iraq. And it's hard to be in the middle between American soldiers-- I don't want to say that American soldiers are arrogant or something like that, but it is an army kind of life. And those policemen are being very sensitive, because, well, their country is occupied, their army is being defeated. And now, they have to receive orders and instructions from their former enemy. So you have to be very sensitive in order to create a kind of, let's say, a friendship, a kind of common understanding between the two parties.

Ira Glass

And so give me an example of an order the way the Americans would say it, and what you would have to do to it in order to get it across.

Basim

Yeah, like for example, I used to have a boss who is a lieutenant colonel in the American Army, who was very keen on the hygiene of Iraqi policemen, or on the cleanness of their police station. And we are in Iraq, we have the tradition to smoke everywhere. We can smoke in any place we want. And that Army commander was very keen on seeing Iraqi policemen, for example, throwing the butts of their cigarettes on the ground. And he used to follow them one by one, telling them to pick the cigarettes butts up from the ground and put it in an ashtray, or in a trash basket where it belongs.

And sometimes, a form of military order like that would be interpreted in a bad way, like the Iraqi policemen would think, OK, this is my police station, this is my country. I can do whatever I want. I can throw my cigarette butt whenever I want, or wherever I want. So when you interpret a situation like that, where you have an American commander telling an Iraqi policeman, hey, don't just throw the butt of your cigarette on the ground, it would have to be interpreted in another way, like, well, do you think that somebody is going to come and clean that after you? So please be very kind, and when you smoke, please be aware that you have to throw your cigarette butt in a place where it reflects a good image of your police station. You don't want the Americans to think that you are dirty or something. And this is how we interpret situations.

Ira Glass

Basim, why not just turn to the Americans and say, well let these men be. This is our culture here, we throw the cigarettes. What difference does it make?

Basim

Well, because I have this kind of belief that if we listen to those people, to the Americans, things would be better for us. We need this kind of education. And it starts from small things, and it grows up to the big things. If the American soldier or commander have the time to teach you where to throw your cigarette, then he would be teaching you how to treat your prisoners. He would be teaching you how to have like a professional ethics. He would be teaching you how to do much more important things.

Ira Glass

And also you're working for him. It's your job to say what he wants you to say.

Basim

And this is one part of the story, yeah.

Ira Glass

The more you tell these stories, the more it's clear that your job is so much more than translating the words.

Basim

There is a situation where I was with a new boss. We have received somebody who is a Major in the army who was in charge of our unit, and I had to lie to him in one incident. Because we went to the City Hall in the city of Mosul, trying to do some security assessment of the building itself. And there were about 150 or more Iraqi protesters who are protesting against the Americans at that point. And our new commander has said, well, we have to do it no matter what. We have to do that assessment today. And I told him, but there are protesters who can be provoked by our existence, like we with our Humvees and with our weapons and stuff like that. And he said, no, it doesn't matter.

And I was talking to an Iraqi policeman who said, well, you can do the assessment now-- he's a high ranking officer in the police-- and we can manage with the protester if they got any kind of action, or if they start to throw stones or something like that. And the way I translated it to the American officer, I told him that the Iraqi officer was saying that we should leave right now, because we don't want to provoke the protesters, we don't want to use their weapons against them today. And the American officer thought about it and said, yeah, let's do the assessment another day.

In a situation like that, the Iraqi officer did not have the right judgment about the situation, because those protesters were very angry. And the American officer has his schedule, has his plan, he wants to do the building security assessment. But I was the only one who can see a group of Iraqi people who were angry, and who can start throwing stones, and somebody can get in the middle of them with a weapon or with a rifle and start shooting, and the Americans and the Iraqi police will shoot back, and there will be casualties, which is something that can be avoided. In a situation like that, I thought this is the only lie that I felt very comfortable about.

Ira Glass

When you study to be an interpreter, did they tell you to be completely neutral?

Basim

Yes. I know that. But we have not received any kind of study, any kind of academic study on how to be translators in a war situation, in a battlefield, if you know what I mean.

Ira Glass

I know. What's interesting about these examples is that it's not just that you're just interpreting what's going on, but in a sense, you're taking over for whoever's in charge. Do you know what I mean? With the protesters, you're saying that you know better what's going to get everyone through the situation, and you're actually taking over.

Basim

Yeah, because if something wrong happened, where the Americans whom I work with have to shoot some people who are demonstrating and people got killed, or other people got wounded, or an American friend of mine got killed or got wounded, I would never forgive myself because I didn't take an action, because I didn't took a stand. Because I have to do something. We have to avoid tension, if you know what I mean.

Ira Glass

The Army unit that Basim was working with trained Iraqi police. This meant that Basim spent a lot of time translating American police manuals into Arabic, and transiting lectures about police procedure. And as an Iraqi who had always been afraid of the police under Saddam, when police seemed able to do whatever it is that they wanted, Basim really liked this part of his job, teaching Iraqi police to work the way the police operate in modern countries, Western countries. On how to treat detainees, how to respect prisoners' human rights. How to stop a riot without brutality. How to exercise authority fairly, without taking bribes.

And so in April, 2004, when photos from Abu Ghraib prison became public, it was especially disheartening to Basim. This is not what he believed the Americans were all about.

Basim

For me as a person, it was just like the shock of my lifetime, because it was the total opposite of what we were teaching the Iraqi prison guards on how to treat and deal with the prisoners. And that was the biggest thing that has turned most of the Iraqis against the Americans. Even those Iraqis who were somehow supporting the American were very afraid to show their support to the American. They couldn't show any kind of support to the American anymore.

Ira Glass

You mean after Abu Ghraib?

Basim

And here comes the loud voice of religious men and the tribal leaders in my city. They said that everything that the American has came with is just a lie, just like their democracy, just like their liberty, just like their freedom of speech. This is what they do to you if they arrest you, even if it was a wrongful arrest, or something like that. This is nothing that I was fighting for. This is not the thing that I was willing to see happening again in my country. We have seen and heard too many examples of torture, of abuse of prisoners in Saddam's time.

Ira Glass

During this period, it became much harder, Basim says, to convince Iraqis that the Americans were doing anything good.

Basim

The unit that I was working with was doing its best, but people were not receiving the message.

Ira Glass

Give me an example of the kind of thing that would happen in those months.

Basim

For example, there were small kids who were just around the American convoys. Those kids, for example, sell CDs, like music CDs, movies to the American soldier. And he gives them candy, and he looks at the things that they are selling, and he tries to help them with $1 or $2. And the next day we hear the imams in the mosque saying that the Americans are distributing porn CDs to the young children who were always around their convoys. Which was really shocking for me because I was there, and I know exactly that the Americans would not do that and I have not seen any incident that the American would do that. Everything was received negatively, at least by the people in my town, in my city.

Ira Glass

Before long, it became dangerous to be a translator. Early in the occupation, clerics had issued an official statement saying it was OK for Iraqis to work with the Americans, including translators. But a year into the occupation, the mood in the country had changed. Translator friends of Basim's were getting killed. One of his teachers, an assistant professor who trained English interpreters at the University of Mosul was killed by people who said that she was graduating traitors.

One day Basim's unit was supposed to process and release a bunch of prisoners who had been transported from Abu Ghraib. Men, they were told, who had been investigated by the Americans and found to have done nothing wrong.

Basim

So one of those prisoners who were about to be released after spending six months in Abu Ghraib prison. He said, we will kill you one by one. And I asked him, who do you mean by killing one by one? The Americans or us, the policemen or the translator? He said, no, you. And for me, I thought, well, this is a man who is totally angry for being in a prison for six months, and who has maybe been treated badly and I measure it out and say that this is an angry man. He would not be killing anybody after he was released. So things like that, those things that I will not be translating, for example. I don't know if I committed a mistake or not.

Ira Glass

You wouldn't tell the Americans he said that he's going to kill you?

Basim

No, I didn't tell them.

Ira Glass

Because you just assumed, well, they will just throw him back in prison?

Basim

Yeah, because I don't like to have anybody, because of me, get back to prison or receive any bad treatment, especially if he was Iraqi.

Ira Glass

Was it frightening?

Basim

Well, I was not frightened, I was surrounded by like 20 American soldiers or something like that. But after I left, and I sat back home with my wife, and I told her, and she said something that made me really frightened, saying that those people, especially those who've been in the prison and who have received bad treatment, will not sit down and feel very happy about they are being released. They will come back trying to get revenge, not necessarily from the Americans but from anybody who they suspect has participated in putting them into prison.

And in that time especially, in early 2004, the word translator itself has became a taboo in Iraqi society. It has became a very scary word, like Sunni religious authorities have suddenly decided that everybody who's working for the Americans is-- forgive me for saying this-- is worse than the Americans themselves. If you have the chance to kill a translator or American, kill the translator first.

Ira Glass

That's such a shocking thing. What did you think? Do you remember where you were standing? What did you think when you heard that?

Basim

The feeling wasn't great, because you're just in the middle of 27 million, most of them thinking that killing you would be better than killing the Americans. So it is just one of those feelings that make you really, really scared. You might not imagine that, or maybe your audience might not imagine that, but speaking English-- like you're walking down the street with your friends, and it came up to your mind that now you are going to speak an English word, this is at some point in Iraq, especially in 2005, 2006, has become enough reason for somebody who do that to get killed. Speaking one word or two words in English in the street, or in the market, or in front of anybody else, would be enough reason for you to get assassinated.

Ira Glass

A few weeks after the prisoner said that he was going to kill Basim, Basim got a threatening phone call. And then a package arrived.

Basim

It was a message printed by a typical printer, by computer. The beginning was some verses of Ram Koran. Then there is this message to me with my full name on it, saying that we have recognized you and identified you as an infidel and a traitor, and a helper of the infidels. And if you don't quit your job at once, you would be killed with all your family. And that was serious because there was a CD disc, a disc, a compact disc with the message, showing the beheading of a friend of mine. Well, he's a colleague more than a friend.

Ira Glass

Another translator?

Basim

Another translator, of course. He's a Christian.

Ira Glass

When you get a DVD like that, did you watch the DVD?

Basim

I watched the first part of it before the beheading started. And that feeling was just indescribable because it is the most scary feeling ever. Seeing it happen to somebody that you know, somebody that you have talked to, somebody that you had conversation with is the most painful part of it, because those monsters were treating him very bad. They knew that they will behead him in minutes, but it was full of insults, and full of bad words. They beated him, they spoke to him very badly.

Ira Glass

Did he speak in the video?

Basim

Well, he spoke his name in a very low voice, because I think his teeth were broken or something. He spoke his name, and they asked him about the nature of his job, so he said, I'm a traitor. It seems like they told him to say so. I haven't finished the rest of the film but I guess you can find it on the internet if you look for it, because they have posted like tens and hundreds of those films.

Ira Glass

And so around this time, your family basically kicked you out of the house, right? They didn't want you there because it made things too dangerous for them.

Basim

They kicked me out of the house. They told me, this is your choice. You are not young. You are an adult. And you don't want us to die because of a decision that you have taken. So it is not enough for you to quit your job now, it has become a necessity for you to disappear.

Ira Glass

Basim went on the run. He hid in another town. But when his pregnant wife gave birth to their son, he drove back after curfew to reach her. A three hour drive in the dark past checkpoints where he had to guess if the checkpoints were Sunni or Shia. When they ask if you're Sunni or Shia, if you give the wrong answer, you're dead. Then he just hid for three months.

Before all this running, he'd actually gone to the Americans to ask for help and for protection. The Americans offered to let him live on the Army base, though without his family. Or they said they would drive him home every night in a military convoy to his family's house.

Basim

At that point I realized that the Americans-- most of them-- have not realized the nature of their enemy. It is not a good thing to be seen in an American convoy that drives you to your home. That will be the cause of the death of maybe my whole family and my neighbors too.

Ira Glass

So in the end, you wanted to be a bridge between these two cultures, between the Americans and the Iraqis?

Basim

Yeah.

Ira Glass

Was it naive to believe that someone could stand in the middle like that?

Basim

No, it wasn't at all. Because most of the misunderstandings, most of the problems that are happening now between the Americans and the normal Iraqi people are due to the lack of full understanding. And in order to achieve that level of full understanding between those totally different group of people, there should be somebody. Our job is building a bridge. If you are a translator, then you build a bridge.

And I always say that if something happened, something wrong happened in the process of building that bridge, the first people who sink into the water are people who are on the bridge, trying to reach out for the other side. And we translators play that role, not only in this war, but in all the wars that happens around the world between nations with different languages. It always happens like that. If I move away, and anybody move away, this would be the best chance for the evil forces, for the terrorism, to control the country, and to cut the bridges that we were trying to build.

Ira Glass

In the end, Basim felt he had no choice. He left Iraq feeling like he should still be there. Today, Iraqis doing translation for the American forces are kind of an endangered species, a hunted species. The company that hired Basim to work for the Americans, Titan Corporation, has had 323 of its interpreters killed while on the job according to The Christian Science Monitor. But when the US Army relies on interpreters from outside Iraq, Basim says, they have trouble with Iraqi dialects, local meanings and customs. And they make all kinds of translating mistakes that no Iraqi would make.

Basim and his wife and his son are now in Europe, in a community where there are a number of Pakistani and Iranian and Iraqi exiles. Back in Iraq, he was constantly having to explain the Americans to people. But in Europe, he's trying very hard to avoid doing that. He specifically tries to avoid telling people that he was an interpreter for the United States in Iraq.

Basim

It is not something to be ashamed of. It is not dangerous here to tell people that I was a translator. But it's just, I wanted to avoid any situation where I have to justify why did I did what I've done in Iraq. And I don't want to be asked by people, now you have been a friend with the American, why did they do that? Why did they do this? So I just don't want to put myself in a situation like that. I just decided that I'm not really with or against the American policy, or the things that the Americans are doing in Iraq. And I don't feel like I have to explain anything to anyone.

[MUSIC - "DON'T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD" BY NINA SIMONE]

Act Three: Redemption By Proxy

Ira Glass

Act three, Redemption By Proxy. When you get right down to it, a reputation is kind of a strange idea. It is this idea about you, about who you really are that is somehow connected to you, but that is utterly abstract at the same time. You can't touch it. You can't pin it down in any exact way, and it changes depending on what you do. Until the day you die, then your reputation is in the hands of whoever cares enough to step in as your proxy and take charge of the historical record and tell people who you really were. Eve Abrams has this story.

Eve Abrams

I taught elementary school for 10 years in New York City at this place called The Neighborhood School. It was one of those schools where students call teachers by their first names and where teachers really get to know their students well-- their families, their strengths, their dramas. But sometimes, one kid stands out. This is a story about one of those kids, and his friend, and his teacher. Sophia is the teacher, and also a friend of mine. Lily was our student years ago. She's 16 now. And Lily's classmate Robert was our student too, but he's dead, so I'll let Lily tell you about him.

Lily Torres

I really had a hard time telling people who had died for a while, because I didn't want to say friend, and I didn't want to say best friend, because that makes it seem like, my best friend. You know what I mean? Anyone can say that they were his best friend. I mean, he lived so close to me, so we'd hang out 24/7. We talked about everything. In our school, everyone was pretty quiet and good, and I don't know, to me, he just seemed like he was different, and he was fun, and everyone else was boring.

Teachers never liked him. He was probably a little bit rude. Like he didn't do his homework. That was like a big thing, because at The Neighborhood School, everyone was like, got to do your homework, got to do your homework, or you're not going to go out for recess and all this stuff. And whatever, he'd be like, never going out for recess because he never did his homework.

Eve Abrams

Robert didn't defer to adults and other kids were drawn to that. But he was also sort of hapless. He was the kind of kid who, when he cut school, got caught.

Lily Torres

He got kicked out of middle school, which was always like really weird to me, because there were so many kids that were so much worse. There was kids that came in that school once a week at 10 o'clock, and like grabbed a girl and left.

I had a crush on him the second I saw him. Fifth grade was the big year that I really had a big crush on him. It was just like, oh my God, I love you. He one time left me flowers at my door-- it was my birthday-- and knocked on the door and ran away. And so I opened the door and there's flowers, and I was like, oh my God, he loves me, like flowers. And so I picked it up and there was a note, and it said: From Robert, To Lily, Happy Birthday. PS, don't get happy. Like, as in like, whatever, don't get happy, don't think I like you because I'm doing this. Don't get happy. I was like, but I am happy because you left me flowers.

I realized it's actually because I liked him so much as a friend, and I never really had somebody that was a boy that I liked so much as a friend. So I figured I must be in love with him or I must like have the big-- but it's also like I just actually always really liked him as a person.

Eve Abrams

That's how Lily saw Robert. Sofia saw him differently. After he was in my class, Robert moved on to Sophia's class right next door, and a lot of times, I'd see and hear them out in the hall together. Mostly I'd hear Sofia. She would lecture Robert about homework and effort and attitude, and her voice got really loud and annoyed. While Sophia lectured, Robert just stood there.

Sophia

Rolling his eyes. I mean, it was more a physical manifestation, just kind of listening to me, but not really listening, kind of looking off in the distance. Head was at a tilt, arms crossed, kind of like waiting for the episode to end.

Eve Abrams

Sophia had a harder time with Robert than I did. He was older by the time she taught him, but his reading wasn't much better, and he still struggled with his schoolwork. He'd also gotten really good at deflecting all of the things that teachers would try-- ordering, cajoling, tricking. Sofia would see Robert around the neighborhood after school, hanging out with older boys, doing nothing much. And it frustrated her to no end that this smart, charming kid seemed headed for a lifetime of dead end jobs and disappointments.

Sophia

At one point, when I was kind of getting near the end of my rope, I talked to his family about making him stay after school in the classroom just so he can get his homework done. And I think we did it for like a week or two, and I don't think it was a very successful-- it wasn't a habit he could replicate at home.

Eve Abrams

Incidents between Sophia and Robert piled up and the year ended badly between them. Someone wrote an obscenity about Sofia on the school wall, up high where only a tall kid could write, and our principal was convinced it was Robert. He ended up being banned from the big end of the year party. When Robert didn't show up at graduation, other kids at the school, including Lily, blamed Sofia, even though Sophia had nothing to do with it. Not going had been Robert's decision.

Mostly, Sophia felt she'd done the best that she could with Robert, but she wasn't sure. She felt bad when she thought about him-- bad for not reaching him, bad for having been hard on him. And for the next few years, she dreaded seeing Robert around the neighborhood, especially with other kids she knew, like Lily.

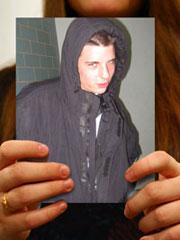

And then one day Sophia heard Robert was dead, stabbed to death for reasons no one knows, even today. He had just turned 16 two weeks before.

Sophia

After Robert was killed, I had this nightmare. I dreamed that two or three of the girls in that class were really upset with me, and they were talking about the time when I had asked Robert to stay after school and work on his homework. One of the girls had accused me of preventing him from joining a basketball league. And she said that because I didn't let him do that, because I made him stay after school to work on his homework, he didn't get a chance to make better friends, and do something that was better for him and more productive. And it really felt like maybe they have something there.

Eve Abrams

If nothing else had happened, Robert would have stayed like that in Sophia's head for years-- a kid she always had regrets about, always wished she'd done a better job with. But about six weeks after Robert died, Lily came back to her old elementary school and showed up in Sophia's classroom out of the blue, and she did something none of our students had ever done.

Sophia

I was surprised to see her, of all people, in my room, in my class, visiting me. And then she said, I wanted to give you this, and she handed me a note that she'd written, and then she left. And then when I read the note, I couldn't believe-- I just couldn't leave. I had to read the letter over again. I keep it in my wallet. I wanted to frame it. But sometimes I feel like I just need to read that letter again, just to remind me.

Eve Abrams

Would you mind getting it now?

Sophia

Sure, I'll read it. Dear Sophia, this is a letter of appreciation to you from me and Rob. Thank you very much for coming to Rob's wake. I know it would have meant so much to him to see how many people showed up. In the past three years, well, four years since me and Rob left The Neighborhood School, we have been best friends together every day.

I just wanted to let you know how much Rob appreciated what you did for him as a teacher. Whenever we would talk about the past, he said that he understood everything you did for him, and that he was grateful for it. He showed me that people care for you, that's why sometimes they are harsh. For that reason, I thank you for teaching it to him. Rob always liked when people showed him they cared. He cared for you very much. Hope to see you soon, Lilly Torres.

Eve Abrams

Lily wrote the note to Sophia on an impulse while she was grieving. She wasn't sure if it was the right thing to do, or if it was weird, or even if Robert would approve. But before she could talk herself out of it, she sat down at her kitchen counter and wrote it on a pink PostIt.

Lily Torres

I think the thing is I really wanted people to know that he was a really great person. I mean, teachers were just always not liking him. And I just maybe thought maybe even if one teacher that he had knew that he liked them, or that-- not to change his reputation with every teacher that he ever had, but I was just trying to take a little bit of the bad off of his name, because I don't think he really deserved any bad at all.

He was so mature about that whole thing about her and I wasn't at all. I thought maybe by showing her that, that she would know that he actually turned out pretty well. He said, I'm not mad, because I think that she was trying to do the best thing that she could for me, because we are talking about Sophia. I was just kind of like, she didn't how to handle you. And he was like, what are you talking about, she didn't know how to handle me? I was bad and she was just trying to help me. And he said that he was thankful that she took the time out to even care about him, even if it was yelling, or whatever it was, he said that it showed him that she cared.

Eve Abrams

Sophia never wrote back to Lily. She'd wanted to find the perfect way to thank her, but she couldn't decide what to say. And then she figured too much time had passed. Though Lily doesn't see it that way.

Lily Torres

It's fine if she doesn't write me back. Or if she does, I don't think it's ever too late. You just never know what people need to know.

Eve Abrams

Until I spoke to her, Lily had no idea how much her note had meant to Sophia. That Sophia kept the note in her wallet, that it had lifted away years of guilt. For Lily, the note was about saving Robert, the part of him that was left in the world. She hadn't realized that it would also rescue Sophia.

Ira Glass

Eve Abrams, in New York.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well, our program was produced today by Lisa Pollack and myself, with Alex Blumberg, Jane Feltes, Sarah Koenig, and Nancy Updike. Our senior producer is Julie Snyder. Adrianne Mathiowetz runs our website. Production help from Seth Lind, Tommy Andres, PJ Vogt, and Emily Yousef. Music help from Jessica Hopper. Special thanks today to Dan Ephron, Sean Cullen, Dan Calhoun.

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. Support for This American Life is provided by Saab, founded by 16 Swedish aircraft engineers who decided to bring the spirit of flight down to Earth. Saab, born from jets. Learn more at saabusa.com.

Support for PRI comes from PBS, featuring their new series inspired by Car Talk, Click and Clack's As The Wrench Turns, premiering Wednesday night on most PBS stations.

WBEZ management oversight for our program by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia. You know, I tried to bring to him to my weekly basketball game. I tried, I tried, but it just didn't work out.

Davy Rothbart

He didn't understand that he couldn't come out on the court when the grownups were playing, and I had to leave the game and take him home.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass, back next week with more stories of This American Life.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.