368: Who Do You Think You Are?

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

I want to play you this moment that happened to get captured on tape. But to fully appreciate this moment, you need a little background. This was recorded in Hoboken, New Jersey. And Hoboken is this old city on the water with these tiny, narrow streets. And because of the way the streets are laid out, parking is just a huge issue there. It is always impossible to find a parking space. And they'll ticket you if you go just an inch or two into a no parking zone. Very strict, that is, for most people. Some people, apparently, never get tickets.

And a couple years ago, this started to bother a woman named Kathy Mallow. She was outside on the sidewalk a lot walking her dogs. And she kept seeing this car belonging to this B-list character actor who's in the movies. And this car would always be parked in front of this one Italian restaurant, blatantly illegal, over and over. And when she would go to the cops about this, they did nothing, which was, of course, infuriating, and seemed so unfair. And not really knowing what else to do, she started photographing the actor's car. So she all of these photos taken over the course of months-- this car sitting there, illegal, no ticket. She became, really, kind of obsessed. Her nickname now in Hoboken is the Hoboken Hall Monitor. It's really at a point where she worries sometimes that she comes off as a crazy person. OK, that's the setup. That brings us to this tape.

Kathy Mallow

Hey, Ron. How are you?

Ron

Good, how are you? How's everything? How's the cat?

Ira Glass

Kathy is walking down the street. And she's the kind of person who knows everybody she passes on the street.

Kathy Mallow

Is that Tessa?

Tessa

Yes.

Kathy Mallow

Hi, Tessa.

Ira Glass

And she's with her neighbor, Tracy. Tracy Roland is a reporter. And Tracy is rolling tape because she is asking Kathy to explain about the movie actor's car.

Kathy Mallow

I would see it every day at the same time because-- oh here's a parking utility guy. What's he doing?

Ira Glass

What he's doing is parking his black city SUV. This is an official vehicle, marked Hoboken Parking Utility-- that's the Hoboken parking police-- in an unmistakable no-parking yellow zone, on the Northeast corner of 1st and Bloomfield. And then, the guy, who is in uniform with a badge, gets out and walks to a bar.

Kathy Mallow

He's leaving his illegally-parked vehicle.

Tracy Roland

Do you want to ask him about it?

Kathy Mallow

Yeah. Do you want to ask him about it?

Tracy Roland

Yeah. OK.

Kathy Mallow

Hi. Do you mind answering a question about your car?

Parking Authority

I'm sorry. I can't.

Tracy Roland

Do you want to tell us--

Kathy Mallow

Why is your parking utility van parked so illegally, including into the pedestrian crosswalk?

Parking Authority

I'm running in there. I'm going to tell my friend something. Is that all right with you?

Kathy Mallow

Oh, OK. Going into Buskers to talk to a friend. Nice.

Parking Authority

Yeah, to talk to my friend.

Tracy Roland

Great. We were just wondering why the parking authority is parking illegally.

Parking Authority

I didn't do nothing wrong.

Kathy Mallow

Oh, you don't think that's wrong to have your vehicle parked illegally like that?

Parking Authority

Not at all. It's fine.

Kathy Mallow

Your vehicle is fine? Your vehicle is into the pedestrian crosswalk, and your vehicle--

Parking Authority

No, it's not. No, it's not. If you go over there and look, you're going to see it's not in the pedestrian crosswalk.

Kathy Mallow

And how far is it from the curb?

Parking Authority

It's fine, though. Is it blocking the crosswalk, though?

Kathy Mallow

Yes. And it's parked illegally.

Parking Authority

You think so. So go walk right over there and I bet you won't get [UNINTELLIGIBLE].

Kathy Mallow

OK, thanks a lot. Thanks a lot for taking on really conscientious responsible behavior. I really like paying your salary.

Parking Authority

You're very sarcastic, ma'am.

Kathy Mallow

I really like paying your salary.

Parking Authority

You really have problems with yourself.

Kathy Mallow

I really like paying your salary.

Parking Authority

You really have problems with yourself. Get a life.

Kathy Mallow

No, I think you have problems taking responsibility.

Parking Authority

Get a life.

Ira Glass

I hope you could hear that last part. After she says, I really like paying your salary, he says, get a life.

Kathy Mallow

See? He completely denied that he was parked illegally. Imagine that--

Tracy Roland

Well, you know--

Kathy Mallow

--over and over and over again. And then, that is the same thing that I get when I've addressed it before-- get a life. Like somehow, if you notice this sort of thing and you want the rules to be enforced correctly, you're somehow supposed to get a life. And you're just not supposed to question the sense of entitlement.

Ira Glass

Yes, it's just parking. But what kills Kathy is how blatant it is. Right there on the street, this daily proof that everybody does not have to obey the same rules. Who do they think they are? Well, today on our radio show, it is an unfair world. And sometimes it makes you crazy, the things that people above you get away with. And then, something happens like, for example, a black man becomes president of the United States, just to choose an example at random. And really, you would have to have a heart of stone not to feel hopeful.

And so today, in this historic week, we have stories of insiders and outsiders, the haves and the have nots, and people staring across the divide between the two groups, trying to figure it out. From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass. Our show today in three acts. Act One, Hard Times, we have voices from our country's past when lots of haves got turned into have nots. Act Two, we talk a little about Tuesday. Act Three, Putting the Cart Before the Porsche. In that act, reflections on a life at the top from a teenager who was there. Stay with us.

Act One: Hard Times

Ira Glass

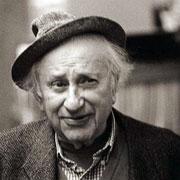

Act One, Hard Times. A week ago, Studs Terkel died. He was 96. Oral histories were around before Studs started doing them, but he pretty much redefined them and did them so amazingly well that anybody who comes after can't help but be influenced. When Studs did an interview, it was history, and it was character study, and it was dramatic storytelling, and it was entertainment all rolled up into one. We all stand in his shadow, all of us who pull out tape recorders and talk to people who aren't famous or powerful or newsworthy in the normal sense.

Around the country, if you've heard of Studs, it's because of his books-- Division Street, The Good War, Working. But he was a radio man. In Chicago, you could hear him on the radio for most of his career at WMFT, and in the last decade, at the radio station our show comes from, WBEZ. Today, in remembrance, we bring you some of the interviews that he collected for his book about the Great Depression, Hard Times. This historic week, when another Chicagoan made some news, it has really been a pleasure to listen to these voices from the past talking about the sweep of change that this country has gone through. These were first broadcast as a 12-part series back in 1971, though Studs had been gathering these interviews for years, preparing for his book. Anyway, here he is.

Studs Terkel

In recalling an epoch some 30, 40 years ago, my colleagues experienced pain in some instances, acceleration in others. And often, it was a fusing of both. A hesitancy at first was followed by a flow of memories, long ago hurts and small triumphs, honors and humiliations. And there was an occasional laughter, too. Are they telling the truth, these oral historians? The question is as academic as the day Pontius Pilate asked it, his philosophy not quite washing out his guilt.

It's the question Pa Joad asked of Preacher Casy, when the ragged man, in a tranchant camp poured out his California agony in the novel Grapes of Wrath. Pa said, "Suppose he's telling the truth, that fellow?" The preacher answered, "He's telling the truth, all right. The truth for him. He wasn't making nothing up." "How about us?" Tom Joad demanded. "Is that the truth for us?" "I don't know," said Casy. "I suspect the preacher spoke for those whose voices you hear, in their rememberings are their truths. The precise fact, or the precise date, is of small consequence. It's simply an attempt to get the story of a holocaust, known as the Great Depression, from an improvised battalion of survivors."

Studs Terkel

If I say to you the Great Depression--

Jane Yoder

Oh, this suggests struggle. This suggests struggle for survival, survival just to be warm. To have bread and Karo syrup was a treat. Anything you brought in the house that was food, [SPEAKING CROATIAN] did it cost a lot?

Studs Terkel

Was that a Croatian phrase?

Jane Yoder

Yes. No matter what you brought in, if you brought bread and eggs and Karo syrup. I don't remember so much my going to the store and buying food. I must have been terribly proud, and felt I can't do it. But how early we all stayed away from going to the store. Because we sensed that my father didn't have the money. And so we stayed hungry. And then I can think of when the WPA, the Workman's Project Administration, came in. And my father immediately got employed on the WPA.

And I remember how stark it was for me to come into training and have girls-- one of them, who lived across the hall from me at Patton Memorial, whose father was a doctor in Michigan-- I can think of people and how it struck me of their impression of the WPA. Because before I could ever say my father was employed on the WPA, discussions and bull sessions in our rooms immediately was, these lazy people that don't do a thing, the shovel-leaners. And I'd just sit there and listen to them. And then I'd look around, and I realized, sure, your father's a doctor in St. Joe, Michigan. Well, how nice. In my family, there was no respectable employment. There was no-- until I thought, you don't know what it's like.

Robin Langston

My father had a restaurant.

Studs Terkel

This was where?

Robin Langston

This was in Arkansas. And when I knew the Depression had really hit with full impact, the electric lights went off. Parents could no longer pay the $1 electric bill, which had amounted to, maybe for a month or two months, $1.80 at the most. And kerosene lamps went up in the home and in the business. Over each individual table in the restaurant, there was a kerosene lamp. This did something to me. Because it let me know that my father wasn't the greatest cat in the world, and I had always thought he was, you know. But it also let me know that he could adjust to any situation. And he taught us how to adjust to situations.

Now, we were fortunate compared to the situation of other people. We always had food. There was never any money, but who needed money then? The restaurant went right through the Depression. We were selling hamburgers for a nickel, Studs. My father would have a meal ticket. You could get a full-course meal-- that is, meat and three vegetables-- for $0.25.

I remember distinctly feeding little snotty-nosed white kids. My father and mother just did this out of the goodness of their heart. I guess there must have been 10 white families within 50 feet of us. And I remember feeding them. I remember my parents feeding little black kids. I remember when the times got so hard, the sheriff pawned a radio to my father for $10. This was a white sheriff, a white official, who had to come to a black man to get $10. The reason he needed the $10, he had some people out of town. He wanted to bring them there to eat some chicken.

Studs Terkel

Do you think a Depression of that intensity could come again?

Robin Langston

I think it could come again. But I think it would behoove the federal government not to let it come. Because you're dealing with a different breed of cattle now. See, now, if they really want anarchy, let a depression come now. My 16-year-old son is not the person I was when I was 16. He's an adult at 16. He's working in a department store and going to school, too. So he has manly responsibilities. And he doesn't want any [BLEEP]. These kids now do not want it. When I was 16, I wasn't afraid to die. But the key at 16 now is not afraid to kill.

Jerome Zerbe

From 1935 to 1939, I worked at El Morocco. And I invented a thing which has become a pain in the neck to most people. I took photographs of the fashionable people and sent them to the papers. These were the women who dressed the best. These were the women who had the most beautiful of all jewels. These were the dream people that we all looked up to and hoped that we, or our friends, could sometimes know and be like.

Studs Terkel

Do you ever talk about what happened outside? There were breadlines. There were various other things occurring, not too nice, you know.

Jerome Zerbe

As I remember, I don't think they ever mentioned them. Never, socially. Because-- I've always had a theory. When you're out with friends, out socially, everything must be charming. And you don't allow the ugly. We don't even discuss the Negro question.

Studs Terkel

What was happening around the city? Do you remember the people talk of breadlines, or Hoovervilles, or apple sellers?

Jerome Zerbe

No, there were none of those.

Studs Terkel

No.

Jerome Zerbe

Not in New York. Never, never. There were a few beggars.

Studs Terkel

New deal.

Jerome Zerbe

New deal? Well, that was an invention of Franklin Roosevelt's that meant absolutely nothing except higher taxation. And that he did.

Studs Terkel

The '30s society, a last image.

Jerome Zerbe

It was a glamorous, glittering moment.

Ward James

Well, I lived off friends. I had a very good friend who cashed in all his Bonus Bonds to pay his rent. And he had an extra bed, so he let me sleep there. I finally went on relief, which was an experience I wouldn't want anybody else ever to go through in New York City. A single man going on relief, at that particular time, was just-- well, it comes as close to crucifixion as you can do it, without the actual mechanical details.

Well, it was '35 or '36, in that area. It was after I lost my job with the publishing house. And I needed whatever money I could get anywhere. The interview was, to me, utterly ridiculous and mortifying. But it was questions like, well, what have you been living on? Well, I borrowed some money. Who'd you borrow it from? Friends. Who are your friends? Where have you been living? I've been living with friends.

Well, I wish I could recall the whole thing. This went on for a half an hour or something. I finally turned to the young man who was interviewing me and said, I've been talking about friends. Do you happen to know what a friend is? And a little after that, I got my-- at least the interview was over. I did get certified some time later. I've been trying to remember how much they paid. It seems to me it was $9 a month.

Studs Terkel

$9 a month. But the thing you remember is this humiliating experience.

Ward James

That's right. Well, I suppose there's some reason in the back of it. I'm a single man who was white. Why didn't I have a family? And I had sent my family West to Ohio, where they could live simply.

Studs Terkel

But they asked, then, all these personal questions.

Ward James

It was-- well, I don't know. I came away feeling like I hadn't any business even living any longer. I was imposing on somebody's great society, or something like that.

Studs Terkel

And now we come to the voice of Elsa Ponselle, who recalls her young womanhood as a schoolteacher during the Depression.

Elsa Ponselle

My nephew, not so long ago, said to me-- in regards to the Negro problem-- ah, if they want a job, they can get it. I said, if you ever say that again, I don't care if you are damn near 40 years old, I'll slap you. I said, your father couldn't get a job during the Depression. And he wanted one. Well, of course he's forgotten. I mean, he never even knew. But I mean, I felt all that old rage coming back. I mean, like, when I was in my 20s. And somebody said, oh, if they want a job. If they really want to work, they can get it.

And so the Depression was a way of life to me. I mean, consider that from the time I was 20 to the time I was 30, I lived in a Depression-oriented universe. And I thought, unconsciously, that that was the way it was going to be forever and ever and ever, that people would have trouble getting jobs, that they would be living in fear of losing their jobs. You know, that fear of losing their jobs.

During the Depression, when you were poor, you weren't looking around and seeing, here is a society in which everybody has something except me. And by God, I'm going to get some. I mean, I can't blame people for feeling-- they read the papers and they watch television and everybody is so rich and has everything-- why not me?

You see, that was the difference in the Depression. It wasn't only not me, but it was not you, and it was not my friends, and everybody else. And the rich had the instinct of self-preservation. They didn't throw the fact that they had money around, if you'll remember. We heard about how they didn't have the fancy debutante parties, because after all, it was not the thing to do.

Studs Terkel

They're a bit more discreet about it.

Elsa Ponselle

Indeed. They were so God damn scared they'd have a revolution. They damn near did, too, didn't they?

Studs Terkel

You felt that? You felt they were scared?

Elsa Ponselle

Oh, were they scared! What's more scary than $1 million? Which you can send over to the Swiss banks, and they're still sending it over to the Swiss banks.

Studs Terkel

Well, this leads to several questions. Then, the question of status did not make itself felt, then? Because your neighbor, everybody you knew was like you.

Elsa Ponselle

That's right. Your neighbor was losing his house. Somebody else was having their furniture taken away. And everybody was in the same boat. And in fact, I think people who were not in that boat were a little apologetic because they weren't suffering. And then, of course, the war came. And the Depression was cured by a war, which was one hell of a note. And all these kids that I had had, who were growing up, disappeared. And it was very, very quiet. The young were gone. And some of them came back, and some of them didn't.

Virginia Durr

In Jefferson county, about 4/5 of the people were on relief. And there was no government relief. So this meant that they had just this $2.50 a week that the Red Cross provided them, and what they could beg, borrow, or steal. But the thing that also struck me as being so terrible was that, just the way my mother and father had this terrible feeling of shame and guilt, and there was that failure that lost all their property, these people had the same feeling of shame and guilt when they lost their jobs.

And they didn't blame the Republic Steel Company or the United States Steel. They didn't blame the capitalist system. They just blamed themselves. And they thought-- well, they would say in the most apologetic way, well, you know if we hadn't bought that radio, if we hadn't bought that old secondhand car, if we'd saved our money and-- you know, they really blamed themselves. And it was this terrible feeling they had of shame that they were on relief.

Mary Owsley

We just drifted back and forth. He was discontented everywhere. And then, we went back to Oklahoma the last time in January of 1929. And I had three children born there.

Studs Terkel

You remember situations of how they got the families around there, too?

Mary Owsley

Oh, yes. I remember several families there that lost their homes and everything they had-- their bank account and everything they had-- and had to leave there in covered wagons, for instance.

Studs Terkel

Covered wagons?

Mary Owsley

Covered wagons, absolutely they went out of there in covered wagons, in the '30s.

Studs Terkel

Do you remember people taking part in demonstrations of any sort?

Mary Owsley

My husband went to Washington.

Studs Terkel

Your husband did?

Mary Owsley

Well, indeed he did. He marched with that group that went to Washington. Let's see, what year was that, Peggy?

Studs Terkel

The Bonus Marchers?

Mary Owsley

Oh, yes, sir.

Studs Terkel

Oh, your husband was a Bonus Marcher?

Mary Owsley

Oh, yes, sir. He was a hellraiser. You know he was in World War I. he was a machine gunner in World War I. And he felt like that the men that fought in the war should have their bonus, especially at a time like it was then-- and then, without employment and with families to support.

Peggy Terry

Mama, don't you remember when Daddy used to say, the God damn Germans gassed me. And I come home, and my own God damn government gassed me.

Mary Owsley

Yes, he said that, too.

Studs Terkel

Oh--

Mary Owsley

He was a machine gunner. And the God damn Germans gassed him in Germany. And he came home, and his own government stooges gassed him and run him off the country up there with water hose, half-drowned him. He was very bitter. Because he was an intelligent man. And he couldn't see why, as wealthy a country as this is-- that there was any sense in so many people practically starving to death, and living in such dire poverty, when so much of it was-- wheat and everything else-- was being poured in the ocean. And many, many things that were happening, that was taking food out of people's mouths and homes. He was very bitter.

Studs Terkel

Peggy, when were you aware of the Depression?

Peggy Terry

I believe, when I first started noticing the difference was when we'd come home from school in the evening, my mother'd send us to the soup line. And we were never allowed to cuss. But after we'd been going to the soup line for about a month, we'd go down there, and if you happened to be one of the first ones in line, you didn't get anything but water that was on top. So we'd ask the guy that was ladling out the soup into the buckets-- everybody had to bring their own bucket to get the soup. And he'd dip the greasy, watery stuff off the top. And so we'd ask him to please dip down so we could get some meat and potatoes from the bottom of the kettle. And he wouldn't do it. So then we learned a cuss, and we'd say dip down, God damn it!

And then we'd go across the street. And one place had bread, large loaves of bread. And then, down the road, just a little piece, was a big shed. And they gave milk. And my sister and me would take two buckets each. And we'd bring one back full of soup, and one back full of milk, and two loaves of bread each. And that's what we lived on for the longest time.

And I can remember-- one time, we didn't have anything to eat. And I don't know if this was before the soup line. But I remember the only thing in the house to eat was mustard. And my sister and me put so much mustard on biscuits that we got sick. And we can't stand mustard right today.

Studs Terkel

You didn't feel at that time-- you and your little friends, your young friends-- a sense of shame?

Peggy Terry

No. I remember it was fun. It was fun going to the soup line, because we all went down the road, and we laughed, and we played. The only thing that we felt was we were hungry, and we were going to get food. And nobody made us feel ashamed. There just wasn't any of that.

Back then, I'm not sure how the rich felt. I think the rich were as contemptuous of the poor then as they are now. But at least among the people that I knew and came in contact with, we all had a sense of understanding that it wasn't our fault, that it was something that had happened to the machinery. And in fact, most people blamed Hoover. I mean, they'd cuss him up one side and down the other-- it was all his fault. Well, I'm not saying he's blameless, but I'm not saying either that it was all his fault. Because our system doesn't run just by one man, and it doesn't fall just by one man either.

Studs Terkel

How much schooling do you have?

Peggy Terry

Sixth grade.

Studs Terkel

You had sixth grade, and then you went to work?

Peggy Terry

Yeah.

Studs Terkel

Then what did you do after sixth grade? You got married at 15.

Peggy Terry

Yes. Well, my husband and me start traveling around. That was just kind of our background. And we just kind of continued it. We went down in the valley of Texas, where it's very beautiful. We were migrant workers down there. We picked oranges and grapefruits and lemons and limes in the Rio Grande Valley. It's really a good life if you're poor and you manage to move around.

Studs Terkel

Well, how did you and your husband get around? What means of transportation?

Peggy Terry

We hitchhiked. I was pregnant when we first started hitchhiking. And people were really very nice to us. Sometimes they would feed us, and then sometimes we would-- I remember, the one time we slept in a haystack. And the lady of the house came out and found us. And she says, well, this is really very bad for you, because you're going to have a baby. And she says, you need a lot of milk. So she took us up to the house. And she had a lot of rugs hanging on the clothesline. She was doing her house cleaning. And we told her we'd beat the rugs for her giving us the food. And she said, no, she didn't expect that, that she just wanted to feed us. And we said, no, that we couldn't take it unless we worked for it. So she let us beat her rugs. And I think she had a million rugs. And we cleaned them. And then we went in. And she had a beautiful table, just all full of all kind of food and milk. And then when we left, she filled a gallon bucket full of milk. And we took it with us.

And you don't find that now. I think maybe if you did that now, you'd get arrested. I think somebody'd call the police. I think maybe the atmosphere since the end of the second war, because all kind of propaganda has been going on. It just seems like the minute the war ended, the propaganda started-- and making people hate each other, not just hate Russians and Chinese and Germans. It was to make us hate each other, I think. I know one thing that people have to get over-- is they have to quit hating black people. That's the first thing. Because you always see yourself as something you're not. You see yourself as better than other human beings. As long as you can hate black people, and as long as you can say, I'm better than they are, then there's somebody below you you can kick.

But once you get over that, you see and you begin to understand that you're not any better off than they are. In fact, you're worse off because you're believing a lie. And in that way, they're smarter than we are, because we couldn't see that. And it was right in front of us. We'd be out in a cotton field chopping cotton. And we'd see the black people over in the next field. But never once did it occur to me that we had anything in common. Because they were black and I was white. And that made it different.

Studs Terkel

You had that feeling of being superior then?

Peggy Terry

Oh, yes.

Studs Terkel

Your husband did, too?

Peggy Terry

Yes.

Studs Terkel

Down in Texas, these are Mexican people?

Peggy Terry

Oh, yes. But I didn't feel any identification with them either. The men and the women, they were just spics. And they should be sent back to Mexico, because they shouldn't be over here in the first place. That was the way I felt at that time. Now, since then, I found out that that very state, we took away from them in the first place. So I feel pretty bad about that.

Studs Terkel

And then, when did this other insight come to you? Any idea when? That feeling you have now.

Peggy Terry

I think maybe it started in Montgomery, because we were living there when the bus boycott started. They hired a bunch of real tough guys to make the Negroes ride the buses. And I saw them pick those women up and throw them on the bus. And a couple of times, I was on the bus myself. And they'd wait until the bus stopped at the corner, and they'd throw those women on the bus. And the women'd just stand there. They wouldn't move. And then when the bus got to the next corner, they'd get off and they'd walk. They would not stay on that bus.

And then my husband got in jail in Montgomery. And I went down to the jail one day to see him. And who'd they have out there, but Reverend Martin Luther King down on the sidewalk, beating him up, about 10 guys. And I felt this was wrong. I don't know why I felt it was wrong. It just bothered me. He was just a nigger to me at that point. But it really bothered me to see a gang beating up on him.

And one other thing that I know really touched me was the store where I always went to buy my groceries. It was a big supermarket. And they had a little, tiny Negro woman. She didn't look like she weighed 100 pounds. And they had her putting up stock. And this great big white guy came in there and filled the shopping cart full of groceries. And then when he checked them out, she was standing there, dusting the shelves. And he says, come here and take these groceries out to my car.

And so she came up there, and she started pushing the cart out the door. And he went out ahead of her. And even though she was taking his groceries-- he was a great big able-bodied man-- he let the door slam on her. He wouldn't even hold the door open for her. So I went and I held the door open. And even when it was happening, I couldn't hardly believe it was happening. And then I said to him something about great big he-men. I don't remember exactly what I said, but it was really nasty, because I felt bad because he did that.

It's really hard to talk about at a time like that, because it seems like a different person. When I remember those times, it's like looking into a world where another person is doing those things. And it's just so hard to relate them to myself.

This may sound impossible, but do you know, if there's one thing that started me thinking, it was President Roosevelt's cuff links. I read in the paper about how many pairs of cuff links he had, and it told that some of them were rubies, and all precious stones. These were his cuff links.

And I just wondered, I'll never forget. I was sitting on an old tire out in the front yard. And we were hungry. And I was wondering why it was that one man could have all those cuff links when we couldn't even have enough to eat, when we lived on gravy and biscuits. And I think, maybe, that was my first thought of wondering why. That's the first thing I remember ever wondering why.

But one thing I did want to say about when my father finally got his bonus-- he bought a secondhand car for us to come back to Kentucky in. And my dad said to us kids, all of you get in the car. I want to take you and show you something. And on the way over there, he talked about how rough life had been for us. And he said, if you think it's been rough for us, he said, I want you to see people that really had it rough.

This was in Oklahoma City, and he took us to one of the Hoovervilles. And that was the most incredible thing. Here were all these people living in old, rusted-out car bodies. I mean, that was their home. There were people living in shacks made out of orange crates. One family with a whole lot of kids were living in a piano box. And here, this wasn't just a little section. This was an area maybe 10 miles wide and 10 miles long. People living in whatever they could jam together.

And when I read Grapes of Wrath, that was like re-living my life, particularly the part in there about where they lived in this government camp. Because when we were picking fruit in Texas, we lived in a government place like that, a government-owned place, in Robstown, Texas. And they came around and they helped the women make mattresses. See, we didn't have anything. And they helped us make-- they showed us how to sew and make dresses. And every Saturday night, we'd have a dance. And when I was reading Grapes of Wrath, this was just like my life.

And I never was so proud of poor people before as I was after I read that book. And just reading that book has made me a better person. I think that's the worst thing that our system does to people, is to take away their pride. And it prevents them from being a human being. And they're wondering, why the Harlem, and why the Detroit? And they're talking about troops and law and order. And you'll get law and order in this country when people are allowed to be decent human beings, and be able to walk in dignity.

Studs Terkel

That was A Gathering of Survivors: Voices of the Great American Depression. The program was produced by Studs Terkel, with Jim Unrath and Lois Baum, of radio station WFMT Chicago.

Ira Glass

Coming up, What a Difference an Election Day Makes. That's in a minute, from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International, when our program continues. It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our show, of course, we choose a theme and bring you different kinds of stories on that theme. Today, we have stories of insiders and outsiders, haves and have nots. And of course, on Tuesday of this past week, an outsider became the biggest inside there is, President of the United States.

Act Two: What A Difference An Election Day Makes

Ira Glass

Which brings us to Act Two. Listening this last week to those old recordings that Studs Terkel made, where people were talking about their view of this country, and of their fellow Americans, and how those views evolved over the decades, I wondered what this election would do, how much it would close the divide between people, particularly between blacks and whites. And I was especially curious about blacks who had seen this country at its worst, who lived through segregation. And looking for somebody to talk to about that here on the radio, I eventually got on the phone with Reverend Donald Sharp, who leads a Baptist Church on Chicago's South Side, Faith Tabernacle. And when I called him and asked him what his thoughts were this week, he was already on the same page that I was.

When I asked him about Tuesday, he started immediately talking about things that happened to him back in the '50s, how he's found himself thinking about those things this week, like being taken as a teenager to see the body of Emmett Till, who was a Chicago kid like him, around his age, who was killed while visiting relatives in Mississippi. Donald Sharp also had relatives in Mississippi.

He told me all kinds of ugly things that happened to him when he was drafted in 1960 and sent to Oklahoma. How he wasn't served food at a restaurant on the way down, even though he was in uniform. How in Oklahoma, black and white soldiers were sent to separate, but very unequal, USO dances, a nice one for the white soldiers, a USO club that was kind of a dump for the black soldiers. He saw things in Oklahoma he'd never seen in Chicago. And that made him angry.

Donald Sharp

That was-- believe me, believe me, believe me, I wanted to go AWOL. I felt like, was it really worth it all? Was this country really worth dying for? I felt as though that I was just a commodity to be used by this country. And my worth to this country has not increased no more than my great-grandfather, who was a slave down in Mississippi. Only thing, I've been permitted to have a little bit more amenities. So all this is a part of who I am, not being able to eat in the restaurant, or going to a segregated dance.

Ira Glass

And so this week, when Barack Obama became president, does it make you adjust how you see this country?

Donald Sharp

I see it a little bit different, but my guard is not totally down. I'm being facetious when I say this-- I'm not going to be around, out singing "We Have Overcome." I feel good for him and his family. And I'm hoping-- I'm cautiously optimistic. I'm happy but, you know--

Ira Glass

Wait, and what's the but?

Donald Sharp

That's the question. The but is my suspicion. See, I still haven't been able to shed my suspicious nature of systemic and institutional racism. Part of the problem is being black, you're living in these two different worlds, one in which you know you're a permanent citizen of, and the other, you are granted visas, shall I say. You go back and forth between these worlds. And I use the term not in a strict medical sense, but you become schizophrenic in your behavior. You're one way over here and you're another way over there.

Ira Glass

And also, at the same time, sometimes you feel like, oh, yeah, things are fine. I'm fine. And other times, you realize, like, oh, no, maybe I'm not fine.

Donald Sharp

Exactly.

Ira Glass

So that feeling of being split, that doesn't end because of one election day.

Donald Sharp

No. Goodness gracious, no. Not by any stretch to the imagination. And so that's my skepticism. Now, I'm quite certain that my grandchildren see it a little bit different. And I hope they would.

Ira Glass

Now, how do your grandchildren see it?

Donald Sharp

They're excited. They're geeked. They're happy. They feel like, boy, it's a new day. But again, they've not experienced some of the things I've experienced. I remember telling my kids, I said, I remember when I would go downtown and we'd change the train in Memphis, I would see two water fountains. There was a sign that said, one white, one colored. And they'd start laughing. They'd say, you really saw that? That really happened? Yes, that really happened.

So what I'm saying is that they've never experienced that, so they don't see things in the same prism that I see it. And so certainly they would be a little bit more excited, shall I say.

Ira Glass

But it's interesting what you're saying, because you're saying that you feel like this is one more step. But when you talk to your grandkids or the young people in your church, you're saying they feel like, OK, the job's done, pretty much. There's a little tidying up around the edges, but they say we're way further along.

Donald Sharp

Oh yeah, they-- oh man, this is it. He did it. And the door is wide open.

Ira Glass

Now, do you think it's possible that they are more right and you are more wrong?

Donald Sharp

I would hope they're more right, I would hope I'm more wrong, but I don't think so.

Ira Glass

Reverend Donald Sharp of the Faith Tabernacle Baptist Church in Chicago.

Kids

Obama will change the world, Obama will change the world! Obama! Obama!

Ira Glass

These little kids on the West Side of Philadelphia on election day near a polling station. They made up the song themselves.

Kids

Obama! Obama! Obama!

Act Three: Putting The Cart Before The Porsche

Ira Glass

Act Three, Putting the Cart Before the Porsche. We end our show about have and have nots with this story about how the other half lives, the rich half, that is. This was recorded in front of a small, live audience in a theater in New York City. We are not going to mention the performer's name. And we're actually going to beep out the name of the town she's from to protect the privacy of her family. It's a pretty honest story.

Sarah

So my dad has this really annoying phrase that he uses as his blanket statement for everything. And that is, it's all about choices. It's all about choices, Sarah. You get a bad grade on a test? It's all about choices. Yeah, maybe I chose to hang out with my friends as opposed to studying for the test. I get it. You got a point. But he uses it all the time, for everything. It's like, Dad, my car got stolen. It's all about choices, Sarah. I fell and I broke my tailbone. It's all about choices. Because, obviously, it's all my fault.

I think this phrase-- I actually know this phrase-- was born on a weeknight, during the autumn of 1990. Now, the first 12 years of my life, I lived in a upscale neighborhood in the suburbs of Virginia. My dad, he's a lawyer with his own practice. He's got a glittery bass fishing boat, which may not mean anything to all of you, but down there, it's a big deal. He's got a beautiful housewife and four perfect children. Most perfect, right here.

And the picture becomes complete because my mom and my dad both have their own Porsche. But my dad has the classic 911. My mom has the sporty, fierce 928. And my mom's license plate, of course, MOMS928.

My mom was not the one to pack your lunch. She was not the one to show up at your PTA meeting. She would wear her expensive jewelry to the pool. This is how she was. But are we going to line up in our Laura Ashley dresses at the Junior Women's Cotillion Holly Ball and the Miller & Rhoads white gloves in party manner and etiquette school? Yes. Yes, we are. And we did.

Now, that was what it looked like on the outside. On the inside, it was not an environment of excess, but one of constraint. Rules were very important. Etiquette, very important. And my dad's insane temper could be set off by the slightest offense. When I heard the Porsche rumble up the driveway every day when he came home, I would run into my room and hide. Because maybe today would be the day that he found the candy wrapper in the sofa cushion and make my mom spank someone.

Or maybe today would be the day that he grabs me by the shoulder and yells at me for language. Because language, in my house, was very important. I mean, curse words, in my house, were extreme. We were not allowed to say gee-- golly gee-- because it sounded like you were about to say Jesus. Unacceptable, not out of a morality standpoint, but out of a, sort of like, we don't want our kids to be trash. OK? Only trash says, golly gee. What? I don't understand.

But they could be very loving, very fun. I know, it's like, what? They could be fun, they could be spontaneous. But it was just all about avoiding awakening the bee's nest.

So it all came to a screeching halt one night in 1990. I was 12 years old. I'm in my room. I'm rehearsing my lines for the school musical, which is an incarnation of the comic strip, Hagar the Horrible. I played the pivotal role of Viking Number Three. And my mom comes in the room, and her face is ashen. And she says, we are having a family meeting. Meet in the den.

Now, we'd never had a family meeting before, OK? Family meetings were for kids whose parents were going to get divorced. That's what they were for. I watched enough TV to know. Enough kids at school-- their parents were getting divorced left and right. And kids whose parents were divorced were like they had some kind of disease. I did not want to associate with them. They were clearly-- they smelled funny, they were poor, they had to go live with their mom in [BLEEP] Park, which was the ghetto because the houses were closer together, and you couldn't have your own pool.

So we go into the den, which is sort of like a men's parlour, with wood paneling and plaid furniture. It's very manly and dark. And my sister's in there. She has magically appeared from her college several hours away. So now I'm like, divorce, divorce, divorce, divorce. My dad looks really bad. Divorce, divorce, divorce, divorce.

My mom speaks first. We're not getting a divorce. Like she knew. Whew, yes, I do not have to become a latchkey kid. And then she's like, but Dad-- Dad has something he wants to tell you. My dad starts to weep openly. And any elation about the non-divorce has now turned to complete dread.

So he finally gets the words out. Daddy did something bad. I took money that wasn't mine. And tomorrow I'm going to turn myself in. And I don't know what's going to happen.

Boom! My brother's like, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. He's like 16. He's an ass [BLEEP]. Whoa, whoa, back up, back up. You mean-- what do you mean, you took money that wasn't yours? Like stealing? My dad's like, yes, what I did was like stealing.

Hey, OK, OK, OK. Was it like stealing, or was it stealing, Dad? You either stole or you didn't. So they press him. My brother presses him for more information.

So he tells us that when he was first starting out in law, a young couple had a newborn child that was mentally retarded. It's just-- I'm sorry. This is, like, so intense for me to even tell you this. I've never told anybody this. This newborn child was mentally retarded, and they believed it was the hospital's fault.

So my dad took the case pro bono. And he worked his butt off. He's like that ad on the subway, like, we fight for injured children. And there's a little leprechaun with boxing gloves on him. That's my dad, all right? So he gets it. And his case was so great that the hospitals decided to settle out of court. And a large sum of money was put into a trust fund for said retarded child. When you're the trustee of a trust fund, that means you can write checks out of the trust fund. AKA, you are entrusted with the money. OK?

So many years after this happened, my dad decided, I'm just going to write myself a check out of this trust fund. And at first, it was just a little bit. And he thought, I'll put it back. No one will ever know. But then a little bit became a lot. And it got out of control. Because he had to pay for those Porsches and the house that goes on forever. And so he tells us all this, and he ends by saying, and we're going to start over. We are going to rebuild our lives.

And I'm over here, who gives a [BLEEP]? What does this have to do with me? And how am I going to help rebuild this family? I'm 12. All right?

So my mom's like, we recommend that you all stay home from school tomorrow, and we can work this out as a family. And I stood up, and I'm like, no. This is just perfect. You always make big announcements before the school play, the night before the school play. Grandaddy died the night before The Wizard of Oz. Here we go again. This always happens. Don't you people get it? When you miss school, you're not allowed to participate in the after-school activities. I hate you. I ran off.

So basically, what happened, I realized, it kind of was a big deal. Everybody at school knows that my dad's a bank robber. And they're calling me one. They think that I am come from a band of thieves and I'm not to be trusted. My parents lose all their friends. We have to move to the ghetto in [BLEEP] Park, which actually is a very nice neighborhood.

They didn't press charges. The family, amazingly, just said, hey, pay it back. [UNINTELLIGIBLE] My dad basically went from a lawyer to being, like, a paralegal. He was disbarred. It was terrible. My mom started doing odd jobs. She changed sheets at a nursing home and was the janitor in our Baptist Church. And it was a free-for-all in my house. Like, what was once very controlled was now like, whatever. Do what you want, Sarah. See you, we're going to go find ourselves.

But my dad was instantly better. He was a better person. He was happy. He chewed gum, which didn't happen before. And he wasn't such an a-hole all the time. And Mom, her transformation was amazing. She basically, just had this deep need in herself to recognize need and suffering in other people. And one day, she just went downtown and packed some bagged lunches-- that she never packed for me-- and took them to some homeless people living under a bridge, which turned into this huge charity, and she helped thousands of people who needed her help.

And she went to Rwanda during the genocide. And she even let a homeless guy named Earl live with us once. He was a fugitive. We figured it out later. But who are we to judge? I mean, who are we to judge, really?

So finally, we never talked about it after that. Except once, my mom and I, about a year ago, were driving around, killing some time before her chemo treatment. And we went to the house that goes on forever. We wanted to see it. And it was very sad looking. And the grass was dead. And it was kind of crumbling.

And we stopped, and I asked her, Mom-- I don't even know why I said it-- Mom, why did Dad turn himself in? And she said, well, your sister wrote him a letter from college that said she loved him and was proud of him and wanted to be a lawyer. And I came home and found him sobbing in the fetal position on the floor. And he said to me, I can't do this anymore. I've made all the wrong choices. And now I'm ready to make a right one. And then he confessed, and he told us that night.

So my mom told me this, and then we sat there in silence. And I said, it's all about choices. And we laughed.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well, our program was produced today by Jane Feltes and myself, with Alex Blumberg, Sarah Koenig, Lisa Pollak, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp, and Nancy Updike. Our senior producer is Julie Snyder. Production help from Seth Lind and P.J. Vogt. Music help from Jessica Hopper. [ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS] This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. [FUNDING CREDITS] WBEZ management oversight for our program by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia, who described his philosophy of broadcasting this way.

Jerome Zerbe

Everything must be charming. And you don't allow the ugly.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

Station Identification

PRI, Public Radio International.