544: Batman

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

So today we have a story that we think might make you believe something that right now you do not believe. And to tell that story, I'm joined here in the studio by NPR science reporters Alix Spiegel and Lulu Miller. Hey there, guys.

Lulu Miller

Hi.

Alix Spiegel

Hello.

Ira Glass

And do I have this right? So you bought a rat, and you brought it to NPR headquarters in Washington, DC?

Alix Spiegel

We did.

Lulu Miller

Alix bought the rat.

Alix Spiegel

I did.

Ira Glass

And where at NPR did you bring the rat to?

Alix Spiegel

We ferreted it into a little kind of edit booth type thing--

[GIGGLING]

Lulu Miller

Hi, buddy!

Alix Spiegel

--type office. And we invited people into the room one by one.

Lulu Miller

So can you just describe what we got here?

Male Speaker 1

It's a rat.

Female Speaker 1

Pinkish ears.

Male Speaker 2

Red eyes.

Male Speaker 3

Long nose.

Alix Spiegel

And sat them down in front of this rat and asked this question.

Lulu Miller

Do you think that the thoughts that you have in your head-- OK, the private thoughts that you have in your head-- could influence how that rat moves through space?

Male Speaker 1

No.

Female Speaker 1

No.

Male Speaker 2

No.

Male Speaker 3

No.

Alix Spiegel

And it was almost unanimous. People did not believe that their personal thoughts would have any effect on the rat at all.

Male Speaker 4

Because that would suggest some sort of telepathy which I don't have.

Alix Spiegel

And Ira, maybe that's what you think too.

Ira Glass

That is what I think. I don't think that people thinking thoughts will affect a rat's behavior.

Alix Spiegel

Well, you're wrong.

Ira Glass

No.

Bob Rosenthal

(CHUCKLING) Yes.

Ira Glass

OK, so who's this?

Alix Spiegel

This is a man named Bob Rosenthal. He's a research psychologist. And early in his career, he did this thing. He went into his lab late at night and hung signs on all of the rat cages. And some of the signs said that the rat in the cage was incredibly smart. And some of the signs said that the rat in the cage was incredibly dumb, even though neither of those things was true.

Bob Rosenthal

They were very average rats that you would buy from a research institute that sells rats for a living.

Alix Spiegel

So then Bob brings this group of experimenters into his lab, and he says, for the next week, some of you are going to get these incredibly smart rats. And some of you are going to get these incredibly stupid rats. And your job is to run your rat through a maze and record how well it does.

Lulu Miller

Can you just pick up the rat?

Alix Spiegel

So, Ira, we actually did a very lo-fi, unscientific version of this in that little room in NPR.

Ira Glass

They let you do that?

Alix Spiegel

We didn't ask permission.

Male Speaker 4

Is that OK to do?

Lulu Miller

Yeah.

Alix Spiegel

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

And you've probably already guessed where this is going.

Alix Spiegel

Yeah. In Bob's real study, the experimenters ran the rats that they had been told were smart.

Female Speaker 1

She has sort of an intelligent looking face.

Alix Spiegel

And the rats they had been told were dumb.

Male Speaker 4

Yeah, he seems kind of lazy.

Alix Spiegel

It was not even close.

Bob Rosenthal

The results were so dramatic.

Alix Spiegel

In Bob's real study, the smart rats did almost twice as well as the dumb rats.

Ira Glass

Wait, even though they were the same?

Alix Spiegel

Yeah, even though the smart rats were not smart and the dumb rats were not dumb. They were all just the same average kind of lab rat. It was so shocking, people didn't really believe him.

Bob Rosenthal

I was having trouble publishing any of this.

Ira Glass

And so what was going on? Like, what was actually happening to make the rats do this?

Alix Spiegel

So what Bob figured out was that the expectations that the experimenters carried in their heads subtly changed the way that the experimenters touched the rats, and that changed the way that the rats behaved. So when the experimenters thought that the rats were really smart, they felt more warmly towards the rats. And so they touched them more gently.

Bob Rosenthal

We do know that handling rats and handling them more gently can actually increase the performance of rats.

Ira Glass

And how does this play out when it comes to people? How do our expectations of other people work?

Alix Spiegel

Well, what you saw in the rats totally holds for people too. I talked to Carol Dweck, who's a psychologist and researcher at Stanford.

Carol Dweck

You may be standing farther away from someone you have lower expectations for. You may not be making as much eye contact. And it's not something you can put your finger on. We are not usually aware of how we are conveying our expectations to other people. But it's there.

Alix Spiegel

And it happens in all kinds of areas. Research has shown that a teacher's expectations can raise or lower a student's IQ score, that a mother's expectations influences the drinking behavior of her middle schooler, that military trainers' expectations can literally make a soldier run faster or slower. So my question was-- you know, how far does this go?

Alix Spiegel

So Carol, clearly these expectation effects exist on a continuum. So for example, if I expect that if somebody jumps off a building, they will be able to fly, that's not going to work out so well, right?

Carol Dweck

Mm-hmm.

Alix Spiegel

So what does science know about where we should draw the line? Does it have a clear sense of that?

Carol Dweck

No. That line is moving. As we come to understand things that are possible and mechanisms through which a belief affects an outcome or one person affects another person, that line can move.

Ira Glass

Well, from WBEZ, Chicago, it's This American Life. Today on our program, we have a kind of hard to believe example of what expectations can do to people. This story is from a new radio show and podcast that Alix and Lulu are launching this week. It's called Invisibilia. It's about the invisible forces that shape human behavior, like beliefs and assumptions and emotions, which I know sounds a little abstract. But in execution, I have to say it is anything but.

Act One: Batman Begins

Ira Glass

Alix used to work here at our program. Lulu worked at Radiolab, and their new show is sort of halfway between the two. A quick heads-up before they launch into this. As you may have noticed, their voices sound a lot alike.

Lulu Miller

They are.

Alix Spiegel

Sorry. Yeah.

Ira Glass

Yes, I know that is not news to the two of you at all. So stay with us. And Lulu, let's just jump right in. Where do you want to start?

Lulu Miller

Well, I'll start with a question that I asked the rat scientist, the expectations guy, Bob Rosenthal.

Bob Rosenthal

OK.

Lulu Miller

Could my expectations make a blind person who literally has no eyeballs see?

Bob Rosenthal

No way. The expectations will not make him see.

Lulu Miller

How sure are you about that one?

Bob Rosenthal

Positive.

Lulu Miller

So I'm deep in the woods of Southern California with a man named Daniel Kish. We've been hiking for hours, climbing over tree stumps and along the edges of a steep ravine. And we're just sitting down in the dirt to take a break.

Lulu Miller

Could we look at your eyes?

Daniel Kish

In terms of them being out?

Lulu Miller

Yeah.

Daniel Kish

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

And then Daniel pulls down his lower eyelids--

Daniel Kish

Let me just--

Lulu Miller

--and removes his eyes. They're prosthetic, of course, and they clink a little bit as he hands them over to me.

Lulu Miller

That's so cool.

Two of the most beautiful hazel-blue eyes I've ever seen in the palm of his hand.

Lulu Miller

Can I hold them?

Daniel Kish

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

OK. Is it OK if my hand--

Daniel Kish

Mm-hmm.

Lulu Miller

Wow. They are so lifelike. Does it feel odd to not have them in?

Daniel Kish

Yes.

Lulu Miller

Oh, it does?

Daniel Kish

Oh, yes.

Lulu Miller

OK.

Daniel's eyes had to be removed when he was just a toddler because of cancer.

Daniel Kish

Retinoblastoma, which is basically eye cancer.

Lulu Miller

And yet he's the one who's led me on this hike deep into the woods. We get to forks in the road, and he knows they're there. He leads me across a footbridge that's maybe two and a half feet wide without slowing down.

Daniel Kish

I think we've passed what I was looking for.

Lulu Miller

And over and over, the path takes us right alongside the edge of a cliff. And Daniel gets within inches but always senses it. So how does he do it? Well, he's got a cane and a hiking stick. But mainly--

Daniel Kish

[TONGUE CLICKING]

Lulu Miller

--he clicks.

Daniel Kish

You press the tongue on the roof of the mouth.

Lulu Miller

Is it kind of like [TONGUE CLICKING]?

Daniel Kish

You're creating a vacuum.

Lulu Miller

Huh.

He clicks with his tongue as a way of understanding where he is in space. This is basically what bats do. Echolocation, the scientists call it. It's like sonar. From the way those clicks bounce off of things in the environment, Daniel gets a sort of sonic representation of what's around him.

Daniel Kish

So here, [TONGUE CLICKING], I can sense trees poking up.

Lulu Miller

Now, Daniel just happened to intuitively invent this when he was a toddler. No one taught him or trained him. He just made it up. And since he's been doing it his whole life, he's now so good at it that he can tell all sorts of things about what's in front of him-- if there's a wall, if the vegetation is dense or sparse.

Daniel Kish

So here's a bench.

Lulu Miller

Yep.

Daniel Kish

Garbage bins.

Lulu Miller

Ding, ding, ding.

Daniel Kish

Outhouse.

Lulu Miller

Wow.

And not only does this allow him to hike--

Daniel Kish

So we'll go this way.

Lulu Miller

--navigate foreign cities alone, rock climb, horseback ride, but the one that gets all the attention is that he can ride a bicycle.

News Reporter 1

Meet Daniel Kish. He's blind, but that doesn't stop him from riding his bike.

Lulu Miller

You may have heard of Daniel Kish before.

News Reporter 2

Daniel Kish is completely blind.

Lulu Miller

He's usually called the Batman.

News Reporter 3

This real life Batman--

Lulu Miller

Because he is the man who clicks, like a bat.

News Reporter 4

His remarkable, bat-like abilities.

Lulu Miller

And he has made the media rounds to demonstrate what is usually described as his most amazing--

News Reporter 5

Extraordinary.

News Reporter 6

Phenomenal.

News Reporter 7

Remarkable.

Lulu Miller

--nearly superhuman ability of being able to ride a bicycle even though he is blind.

News Reporter 8

As you watch him, remember, he can't see a thing.

Lulu Miller

A narrative that Daniel thinks is all wrong.

Brian Bushway

(SINGING) Dee, dee, dee, dee, dee, dee, dee, dee. Step right up! Step right up! The amazing Daniel Kish will demonstrate one of his greatest tricks to date.

Lulu Miller

This is Daniel's buddy Brian Bushway, who has had to watch his poor friend wheel out the old bicycle so many times for the media that he couldn't help but mock the whole set up when I asked him to do it for me.

Brian Bushway

And then he will proceed to mount himself on a bike and ride.

Lulu Miller

And though Daniel indulged, pulling figure eights and riding beautifully as I ran beside him with my microphone, the two of them made it clear that my amazement was kind of offensive.

Brian Bushway

So step right up, step right up, and see the amazing Daniel Kish do something that everybody can, but most people don't.

Lulu Miller

And here's where we get back to expectations. See, Daniel thinks there is nothing amazing about him. He thinks that most blind people who don't have other disabilities could do things like ride bikes.

Daniel Kish

I definitely think that most blind people could move around with fluidity and confidence if that were the expectation.

Lulu Miller

See, he thinks the reason that more blind people don't isn't just because they haven't learned to click. But it's because the expectations that you or I are carrying around in our own heads about what blind people can do are simply way too low.

Daniel Kish

They wouldn't be able to hike. They wouldn't be able to run. They wouldn't be able to engage in manual labor.

Lulu Miller

Daniel, like Bob, thinks those expectations, those private thoughts in our heads, are extremely powerful things, because over time, they have the ability to change the blind person we are thinking about.

Daniel Kish

That psychology becomes inculcated in the blind person, absorbed and translated into physical reality.

Lulu Miller

And so Daniel thinks if we could all change our expectations of what blind people are capable of, then not only would you see a lot more blind people on bikes, but--

Daniel Kish

More blind people could--

Lulu Miller

--in a very real way--

Daniel Kish

--see.

Lulu Miller

Yeah, he just said "see."

Daniel Kish

It's actually pretty simple and straightforward.

Lulu Miller

And it turns out neuroscientists are looking into this idea and seeing some pretty shocking results. And we'll get there. But first, to understand what Daniel means, how expectations could give a blind person vision, we need to first see how Daniel himself shot through this forcefield of low expectations, a story which starts back in 1967, when Daniel was 13 months old, and that second eyeball had just been removed.

Paulette Kish

Oh, my gosh.

Lulu Miller

This is Danielle's mother, Paulette Kish. And a few days after taking her son home from the hospital, Paulette realized she was facing a really difficult choice.

Paulette Kish

My mom thought that I should put him in cotton.

Lulu Miller

Cotton?

Paulette Kish

Wrap him in cotton so that he didn't get hurt, so that he was so protected. That's really how she felt.

Lulu Miller

See, Daniel was a very rambunctious little guy.

Paulette Kish

He started climbing when he was six months old, before he even walked.

Lulu Miller

And that didn't change when he went blind.

Paulette Kish

We had bookshelves he would climb, so I'd have to move everything off the bookshelves, because he would get into them.

Lulu Miller

So Paulette needed to decide, was her mom right? Was it time to start putting some restrictions on him, or was she going to raise him like a seeing child, allow him to explore his world with very few restrictions on him for blindness? And Paulette went with option two. She was going to banish her fear.

Paulette Kish

Just put it away. In the beginning, I think that's what I did. I just put it away.

Lulu Miller

And so, when two police officers showed up at her door--

Paulette Kish

Two big, huge police officers holding my child.

Lulu Miller

--having picked up Daniel for climbing the fence into their neighbor's yard--

Paulette Kish

You can't let him do that. He could fall.

Lulu Miller

--Paulette felt their same worries--

Paulette Kish

It's very scary.

Lulu Miller

--but didn't make Daniel stop.

Daniel Kish

I just climbed everything I could find.

Lulu Miller

And when the elementary school called and asked her to make Daniel stop clicking--

Paulette Kish

It's not socially acceptable, is what they would say.

Lulu Miller

--Paulette said, too bad.

Paulette Kish

He needs to know what's around him, and that's how he does it.

Lulu Miller

And so Daniel clicked, [TONGUE CLICKING], past people doing double takes on the street, [TONGUE CLICKING], occasionally bumping into things.

Daniel Kish

(CHUCKLING) Yep.

Paulette Kish

And then pretty soon--

Lulu Miller

Your blind kid is not only scaling trees and fences by himself, but using just his clicks-- not even using a cane at that point-- he's walking to school by himself, crossing busy roads, exploring his way into neighbors' driveways.

Daniel Kish

A friend of the family had an undersized bike, and I started riding alongside this retainer wall, until I realized I didn't really need the wall and I could roll alongside the wall without having to touch the wall. And then--

Paulette Kish

Oh, goodness.

Daniel Kish

I just could ride it.

Lulu Miller

He'd have to click way more than usual.

Daniel Kish

Peppering the environment with a barrage of clicks. [TONGUE CLICKING]

Lulu Miller

But by six years old, he could do it-- ride completely comfortably on the bike.

Daniel Kish

[CHUCKLING]

Lulu Miller

And when neighbors would pop their heads out the door--

Paulette Kish

How can you let him do that?

Lulu Miller

--with their concerns--

Distorted Voices

How can you let him do that? How can you let him do that? How can you let him do that?

Lulu Miller

--she'd look at his smiling face--

Daniel Kish

[CHUCKLING]

Lulu Miller

--and think--

Paulette Kish

How can I not?

Alix Spiegel

Hey, Lulu?

Lulu Miller

Yeah, Alix?

Alix Spiegel

Can I cut in with a question?

Lulu Miller

Yeah.

Alix Spiegel

Did he ever get hurt? Like, really hurt?

Lulu Miller

Well--

Daniel Kish

I used to have this game, get to the top of our road and yell, dive bomb, and I would ride insanely fast down the road. And everyone would have to scatter. Well, one day, I did the dive bomb thing, and as I was screaming down this road, bang. I just collided into a metal light pole.

Lulu Miller

Oy.

Daniel Kish

Blood everywhere.

Lulu Miller

And this was not the only pole in Daniel's life. On the schoolyard, he ran into a pole and knocked out his front teeth.

Daniel Kish

Teeth.

Lulu Miller

A few years after that, he ran straight into a soccer shed.

Daniel Kish

And it just destroyed my whole mouth.

Lulu Miller

So yeah, he got injured pretty badly a bunch of times. But the way that Paulette reacted to these injuries--

Paulette Kish

Mm-hmm.

Lulu Miller

--was that she always let him keep going. I mean, shortly after the bike thing, a bicycle appeared under the Christmas tree.

Alix Spiegel

And, like, I am a mother, and I think that if my kid kept showing up with his front teeth knocked out, I would begin to wonder if I had made the right choice.

Lulu Miller

Yeah. Paulette knows it seems extreme, which brings me to the reason she decided to do this, to raise her blind kid so differently from the way that most blind kids are raised.

Paulette Kish

It was my first marriage. It was not a good marriage.

Daniel Kish

My father was an alcoholic, and he was abusive.

Lulu Miller

Daniel's biological father, who's now dead, would hit Paulette.

Daniel Kish

Sort of a barroom brawler type.

Lulu Miller

And he was tough with Daniel and Daniel's little brother, taught them to fight.

Daniel Kish

And we had to learn to sort of take physical punishment, as it were, and be able to dish it back.

Lulu Miller

And Paulette says this is why she ended up being so hands-off with Daniel.

Paulette Kish

[SIGH] Everything that happens in your life has its effect, has its effect.

Lulu Miller

She says that after years of feeling so small and powerless in that marriage, when she finally made it out, she vowed never to be ruled by fear again.

Paulette Kish

I mean, there's life, and then there is living your life. There is a difference.

Lulu Miller

And the same would go for Daniel. She refused to let those scary thoughts of what could happen make her keep Daniel too close.

Lulu Miller

But what if Daniel ended up being hit by a car and killed?

I asked her.

Lulu Miller

Like, what if-- what if a car just hits and just plows him down?

Paulette Kish

But that could happen to anyone. That could happen to anyone. There was a group of four kids on the corner up about a block, a car went up the curb and hit them, killed two of them. It could happen to anyone.

Lulu Miller

And so bikes were bought for Christmas.

Paulette Kish

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

And tree climbing was permitted.

Paulette Kish

OK. I'll just close my eyes.

Lulu Miller

And this blind little boy was allowed to wander the world as freely as any sighted child.

Daniel Kish

From the fifth grade on, I walked to school almost every day. I had to cross major streets. I participated in extracurricular activities. I made my own breakfast. I made my own lunch.

Alix Spiegel

I mean, were they considered outside the norm? Did they consider themselves outside the norm?

Lulu Miller

I don't think they noticed it much. I don't think they thought about it much. Particularly Daniel didn't know that there was anything odd about the way he got around the world.

Daniel Kish

Until Adam.

Adam Shaible

My name is Adam Shaible. Excuse me for a second.

Lulu Miller

So Alix?

Alix Spiegel

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

This is where the story takes a kind of complicated turn, because Adam is basically the first other blind person that Daniel ever encounters. They meet in the fifth grade, when Adam suddenly enrolls in Daniel's school.

Adam Shaible

I will say, I was a rather small fellow at the time. When I was 11, 12, I was under 60 pounds.

Lulu Miller

Wow.

And Daniel was not exactly welcoming.

Adam Shaible

He just wasn't a nice-- a nice fellow.

Lulu Miller

Daniel said that Adam completely unnerved him because of how incapable he was of getting around on his own.

Daniel Kish

Literally just running into walls. I mean, he would just walk along, and his forehead would connect with a wall. And we'd be on the other side of that wall, and we would say, OK, that's Adam, he's coming, kind of thing.

Lulu Miller

Is that true? Was it, like, that bad?

Adam Shaible

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

Adam says he had simply never needed to get around on his own before.

Adam Shaible

I went to the School for the Blind from age five to age seven.

Lulu Miller

And there, he was taken around on someone's arm almost all the time. In the lunchroom, people brought him his food. They helped him carry his books, helped him tie his shoelaces.

Adam Shaible

I don't know why people did things for me. They just did.

Lulu Miller

And Daniel was baffled by Adam.

Daniel Kish

At the time, I had not really conceptualized blindness in that way for myself. And I just didn't understand it.

Lulu Miller

He'd come home to his mom mystified.

Paulette Kish

He'd say, Adam can't do anything on his own.

Adam Shaible

If I got lost, I used to get terrified.

Daniel Kish

Why?

Adam Shaible

I just-- I didn't feel safe.

Daniel Kish

Why?

Lulu Miller

And then what happened is that the kids at school started to mix up Daniel and Adam.

Daniel Kish

People started just lumping us together as the blind kids. We were the same age.

Lulu Miller

You were the blind boys.

Daniel Kish

Yeah. They'd mix up our names, and I didn't like that at all.

Lulu Miller

And so almost to prove his distinction from Adam--

Daniel Kish

I did the things that kids will do in situations like that.

Lulu Miller

What did you do?

Daniel Kish

Um--

Paulette Kish

He made fun of Adam.

Lulu Miller

He started bullying him.

Adam Shaible

I wondered if there was something I had done.

Lulu Miller

He'd tease him in front of other kids--

Daniel Kish

I was pretty brutal.

Lulu Miller

--and even beat him up a few times.

Adam Shaible

Yeah.

Daniel Kish

And that, in my aggressive little mind, was the thing that set me apart.

Adam Shaible

I wanted to be his friend.

Alix Spiegel

So then what happened?

Lulu Miller

Um--

Daniel Kish

Time moved on.

Lulu Miller

Adam and Daniel went to different schools, and Daniel just tried his best to forget this kid so like him, who couldn't get around in the world.

Daniel Kish

And um, we just lost track--

Adam Shaible

We just lost track of each other.

Lulu Miller

Daniel goes off to college, doesn't really associate himself with the blind community. His plan is to become a researcher, an autism researcher. And then one day, he happens to pick up this book.

Bob Scott

The title is The Making of Blind Men.

Daniel Kish

The Making of Blind Men by Robert Scott.

Bob Scott

I go by Bob. You can spell that either way.

Lulu Miller

All right.

This is the book's author, Bob Scott, a former professor of sociology at Princeton. And inside this book was the idea that would change Daniel's life, an idea that when you first hear it sounds kind of out there-- that blindness is a social construction.

Alix Spiegel

Wait, was Bob saying that people are not physically blind?

Lulu Miller

Kind of. But let me just tell you how he gets there.

Alix Spiegel

OK.

Lulu Miller

OK?

Alix Spiegel

OK.

Lulu Miller

So fresh out of grad school, Bob got this job to conduct a huge, multi-year long survey to see how effective blindness organizations were at helping the blind.

Bob Scott

Yep.

Lulu Miller

And so he begins interviewing hundreds of blind people, goes out on hundreds of site visits.

Bob Scott

Basically gathering information in any way I could imagine that I could get it.

Lulu Miller

And then one day, many months into the process, he had--

Bob Scott

What might be called an aha moment.

Lulu Miller

He was out walking in a snowstorm in New York City, when he happened to see--

Bob Scott

A blind beggar--

Lulu Miller

--asking for money--

Bob Scott

--standing on the corner at Bloomingdale's.

Lulu Miller

And he thought, hey, someone else to interview for my survey.

Bob Scott

I said, would you allow me to buy some of your time? And I gave him-- I don't know-- $25 or something like that. We went in and sat down at a restaurant, and I said, tell me your story.

Lulu Miller

Turns out the man had worked at a paint factory until a few years before, when an accident there left him blind. And the people at the factory really liked the guy, so they said, look, why don't you go to an organization for the blind, get some training, and then come back and work for us? So the guy said, great.

He went to an organization for the blind. He said, I've got this job all lined up. Can you just help me with a few basic things. And the blindness organization said no.

Bob Scott

Oh, no. You can't do that. Blind people can't do those things. What we're going to do is put you through a program of rehabilitation and then move you along to our sheltered workshop that manufactures mops and brooms.

Lulu Miller

And Bob said there was one sentence in that response that jumped out at him.

Bob Scott

Blind people can't do those things.

Lulu Miller

And he began to wonder, wait, is that true? Could this guy really not work in a paint factory? Because over the course of his research, he'd seen blind people that could do all sorts of things. And the more that Bob looked around, he started to see that message--

Bob Scott

Blind people can't do those things.

Lulu Miller

--being communicated to the blind people by the blind organizations that serve them-- not necessarily always as explicitly as in the case of the paint guy.

Alix Spiegel

Like, how else then?

Lulu Miller

Well, take the fact that at that time, of the almost 20,000 blind kids that were in America, 2/3 of them were being kept on the sidelines in gym class. Play tag, run around on your own--

Bob Scott

Blind people can't do those things.

Lulu Miller

And then there was the organization's insistence that adult blind people get help getting around.

Bob Scott

They are picked up at their homes. They're driven there. They're met at the sidewalk, walked into the agency, escorted to wherever they're going-- everything is being done for them.

Lulu Miller

And even though all this was intended to help, Bob began to wonder if maybe, just maybe, the organizations' low expectations for what blind people could do was in some way actually limiting the blind people that those organizations sought to help.

Bob Scott

What I came to realize is that how they functioned was a process of learning. It was not imposed on them entirely by the fact that they couldn't see.

Alix Spiegel

Hey, Lulu?

Lulu Miller

Yeah, Alix?

Alix Spiegel

So is Bob saying that blindness is mostly in our head? That blind people can actually do everything that sighted people can do? Because my dad is blind, and he is very, very limited in what he can do. And I gotta say, I don't feel like the obstacles that he faces are obstacles that he wouldn't face if he just thought differently about his blindness.

Lulu Miller

Well, Bob is pretty hardcore about this. I think he would say that with enough time, your dad actually could do a lot more, because he thinks the only real absolute physical limitation of blindness is about an inability to perceive things in the distance.

Bob Scott

Exactly, anything that I can't reach out and touch.

Lulu Miller

But you can compensate for everything else. And Alix?

Alix Spiegel

Uh-huh?

Lulu Miller

Bob wasn't actually the first person to come up with this idea. Blind people were. A group called the National Federation of the Blind has for a long time advocated this kind of idea. This is a group formed by blind people for blind people, and they think that the physical condition of blindness--

Bob Scott

It doesn't explain nearly as much as people believe it explains.

Alix Spiegel

So if you buy this logic, people who are blind-- like, the only thing that's standing between them and walking around the world, like Daniel does, is our beliefs?

Lulu Miller

Yeah. You know, that sounds totally crazy, and that is exactly what he's saying. Which brings us back to Daniel. Daniel reads this book, and he starts thinking about Adam.

Adam Shaible

If I got lost, I used to get terrified.

Lulu Miller

You know, maybe it wasn't that Adam was this weirdo, tentative kid but that he was a very typical product of a system.

Alix Spiegel

You mean, like, the system taught Adam that he would have trouble moving around.

Lulu Miller

Yeah. I mean, he was led around school. People brought him his food--

Adam Shaible

I don't know why people did things for me. They just did.

Lulu Miller

And when Daniel looked at the world around him, he thought, you know, a lot has changed. But a lot is frighteningly similar.

Alix Spiegel

From then till today, things are similar?

Daniel Kish

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

Yeah.

Daniel Kish

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

I called around to over a dozen blindness organizations all over the country.

Daniel Norris

My name is Daniel Norris, supervisor of adult services for the Vermont Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Lulu Miller

And supervisor after supervisor told me that what Bob Scott saw is still very much alive today.

Alix Spiegel

In what way?

Lulu Miller

So most children who are blind in America don't actually go to schools for the blind anymore.

Daniel Norris

Right.

Lulu Miller

Thanks to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, most blind kids stay in their local public schools, which is great. But on those public school grounds, says Norris--

Daniel Norris

There is a lot of pressure to keep a child safe, especially in a litigious society.

Lulu Miller

So many of the blind students are still placed with a paraeducator, which can be good. But sometimes--

Daniel Norris

Those paraeducators can end up doing the work for the kids.

Lulu Miller

Like Adam.

Daniel Norris

When you lighten someone's load, you don't allow them to expand.

Lulu Miller

I talked to mothers whose blind kids were pulled off of playground equipment. And perhaps the most chilling thing is the fact that most blind kids will intuitively start clicking--

Daniel Kish

[TONGUE CLICKING]

Lulu Miller

--or snapping or stamping to test out their environment with sound. But they are so often discouraged--

Paulette Kish

It's not socially acceptable, is what they would say.

Lulu Miller

--that they never get the chance to develop their skill to the level Daniel did.

Daniel Norris

So how are we doing as a nation? We have not taught independence.

Lulu Miller

He points out that in America, a majority of blind people are unemployed. And while that could be for a lot of reasons, Norris thinks that's on us.

Daniel Kish

What we are doing is we are creating slaves to others' thinking.

Lulu Miller

That's Daniel Kish again.

Daniel Kish

Slaves to others' perception, slaves to what others think they should be doing. And somehow we're comfortable with that.

Lulu Miller

And so, though he had never wanted to work in the profession of blindness-- in fact, he'd wanted to get as far away from it as he could-- Daniel Kish decided he sort of had no choice.

Daniel Kish

It sucked me in kind of kicking and screaming.

Lulu Miller

He could see what was happening. And he held in his tongue, [TONGUE CLICKING], a way out. So he decided that he would dedicate his life to trying to liberate blind children.

Alix Spiegel

Kind of like Batman?

Lulu Miller

Exactamundo, fighting for good in the world in a kind of vigilante way, because actually, the way that you go about liberating a blind child from the constraining forces of culture, it can get kind of ugly.

Ira Glass

Coming up, the Dark Knight rises. Lulu and Alix are back in a minute, from Chicago Public Radio, when our program continues.

Act Two: The Dark Knight Rises

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Today on our program, we have a story from a brand new radio show and podcast called Invisibilia. It's from NPR News. Science reporters Alix Spiegel and Lulu Miller are the hosts. And they're here today talking about how profoundly other people's expectations can affect us and about a blind man named Daniel Kish. Anyway, again, here's Alix.

Alix Spiegel

So when last we met Daniel, he had decided that he was going to become a kind of real-life Batman who would save people who were blind from the low expectations of their culture. But before we keep going, I should probably point out that lots of blind people don't necessarily want him as their savior. A bunch of them told us, basically, clicks shmicks!

Bob Ringwald

Because I get along just fine without doing that clicking noise, or whatever he calls it.

Alix Spiegel

This is Bob Ringwald, a musician in California. He says he's got a cane. It works great. He does everything he wants.

Bob Ringwald

When I wanted to learn guitar, I did, and I've done a lot of climbing around on my roof and climbing up poles. And anything I wanted to do, I did.

Alix Spiegel

Now, Bob Ringwald-- in fact, all of the blind people that we spoke to for this story-- agreed with Daniel that low expectations hold blind people back. But that didn't necessarily mean that they wanted to echolocate. For example, when Bob Ringwald was seven, in school for the blind back in the '50s, he knew some kids who clicked and said they just seemed a little weird.

Bob Ringwald

I really didn't want to go through life clicking all the time. A lot of people think blind people are strange. So I didn't want to be any stranger than I already was.

Eric Woods

A lot of instructors don't like people to do that, because it does look funny.

Alix Spiegel

Eric Woods is also blind, and a retired mobility instructor in Colorado.

Eric Woods

And it's socially unacceptable-- not unacceptable, but it's socially different. And so it has been discouraged. I've heard plenty of people discourage it.

Alix Spiegel

And Daniel knew this. He knew what he was up against. So Lulu, what did Daniel do?

Lulu Miller

Well, he starts up a nonprofit, as you do-- a nonprofit that will teach people how to echolocate.

Voice On Video

Grace.

Lulu Miller

This is one of his early instructional videos. It's now 2001, and since his aim is nothing short of liberation, he calls it World Access for the Blind.

Voice On Video

World Access for the Blind.

Lulu Miller

Now, the only little problem that he runs into is that at that time, a blind person teaching another blind person how to get around is basically unheard of.

Daniel Kish

The blind cannot lead the blind is right out of the Bible. It's fundamental to our culture.

Lulu Miller

In fact, until the mid '90s--

Daniel Kish

There was no certification for blind people to train other blind people.

Alix Spiegel

Wow.

Bob Scott

Blind people can't do those things.

Lulu Miller

So this is actually when the bike trick became big-- like, though he sort of hates "Look at the blind man ride a bike," he realized that could get him attention. So he starts going on all these TV shows with his trick.

Daniel Kish

And my segment was between something about vampires and some other thing about faith healing or whatever.

Lulu Miller

And on these TV appearances, he'd try to send some sort of signal to blind kids who might be watching, who might be able to contact him.

[APPLAUSE]

Tv Host

Dan, can anyone learn this?

Daniel Kish

Echolocation is a skill-- piano playing, for example. Some people may be more talented than others, but I think that anyone could learn it.

Lulu Miller

And it worked.

Daniel Kish

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

Slowly but surely, families started contacting him, which meant that Daniel was now faced with a question. Could he actually undo the damage of low expectations? And this is where things begin to get a little morally complicated.

Daniel Kish

The example I'm about to give is an example that took place about 10 years ago.

Lulu Miller

Daniel told me about going out to teach one of his first students ever, a little 10-year-old boy.

Daniel Kish

He lives on an apple orchard--

Lulu Miller

Out in Washington state.

Daniel Kish

I come out. And basically, what I see is a boy who won't leave his house.

Lulu Miller

And so Daniel's idea was to get him to climb a tree.

Daniel Kish

They live on an orchard full of trees, for goodness' sakes.

Lulu Miller

But the kid won't budge. So to get him out the door, Daniel takes away all his toys.

Daniel Kish

Our purpose was to kind of simulate the world that he was choosing for himself. So this is what life will have in store for you-- basically nothing, OK? Nothing.

Lulu Miller

And after about a week, the kid finally agrees to go climb a frickin' tree. And he gets up onto the first branch and the second branch and then says, OK.

Daniel Kish

I give up. I give up. Yeah, but you know what? Giving up isn't an option. You can decide never to climb a tree for the rest of your life, but we are going to climb this one. And I said, you can go up, you cannot go down. And he just had a fit-- literally screaming himself hoarse. I mean, he actually jumped at one point. Like, he actually leapt off the tree, he was in such a frenzy.

Alix Spiegel

Oh my god, Lulu. And what does Daniel do?

Lulu Miller

Well, he catches him. He's right below him. And he just says, no.

Daniel Kish

You can go up. You cannot go down.

Lulu Miller

And they stay in this tree battling it out.

Daniel Kish

Inch by inch by-- it took three hours to get up a 60-foot tree.

Lulu Miller

But by the end, the kid was doing it himself.

Daniel Kish

--doing it himself. He started finding his own footholds, finding his own handholds.

Lulu Miller

And Daniel thinks this training and how the parents then took it on too changed the boy's life.

Daniel Kish

By the age of 13, he was out of his shell. He had joined Boy Scouts. That is in no way where he was headed.

Alix Spiegel

Hm. That is just crazy, though, that story, on some level. I don't know if that kind of bullying is even allowed in America anymore, you know?

Lulu Miller

Yeah. And most schools for the blind have been reluctant to hire him because of liability issues. They're scared it'll be too dangerous for their students.

Alix Spiegel

I bet.

Lulu Miller

But see, Daniel would say that attitude, Alix, is part of the problem. So what are a few tears, huh, a few scratches? He has this line he always says.

Daniel Kish

Running into a pole is a drag. But never being allowed to run into a pole is a disaster.

Lulu Miller

He worries that when you prevent a kid from, say, running into a pole, what you end up preventing them from is the kind of experience that allow for-- and this gets me back to that crazy sounding claim he made at the beginning of the show-- actual sight.

Daniel Kish

If our culture recognized the capacity of blind people to see, then more blind people would learn to see. It's actually pretty simple and straightforward.

Lulu Miller

Daniel thinks this because, well, he says he sees.

Daniel Kish

I definitely would say that I experience images, that I have images.

Lulu Miller

And he isn't talking metaphorically here.

Daniel Kish

They are images of spatial character and depth that have a lot of the same qualities that a person who sees would see.

Lore Thaler

Hello?

Lulu Miller

Hi.

Lore Thaler

Hi.

Lulu Miller

This is Lore Thaler, a German neuroscientist at Durham University in the UK. And Lore knows a lot about sight. She studies vision in the brain-- literally how the images we see are constructed.

Lore Thaler

It sounds simple, but an image is actually a complex construct.

Lulu Miller

Several years ago, Lore happened across a video of Daniel.

Daniel Kish

OK, so we had a little string of parked vehicles there--

Lulu Miller

And as she watched the way that he so easily moved through space, she found herself wondering, was there any way that Daniel's brain was indeed constructing images?

Lore Thaler

It was so akin to vision, really.

Lulu Miller

OK, so you may know this already, but Lore reminded me that an image, even though it feels like it's out there in the world in front of your eyes actually exists behind the eyes.

Lore Thaler

The image, it's something that your mind constructs.

Lulu Miller

In a part of your brain called the visual cortex. So Lore brought Daniel and a few other people who can echolocate into her lab, and she took recordings of them while they clicked at different objects in space.

Daniel Kish

[TONGUE CLICKING]

Lulu Miller

A car, a lamppost-- these are her actual recordings-- a salad bowl, a salad bowl in motion.

Alix Spiegel

How do you get a salad bowl in motion?

Lulu Miller

You stand behind the person with a salad bowl on a fishing pole, and you slowly wave it.

Alix Spiegel

Right.

Lulu Miller

And the microphones were actually in their ears.

Lore Thaler

So we recorded what they heard exactly.

Alix Spiegel

Oh, that's neat.

Lulu Miller

And then she played the recordings back to them, one object at a time, while they were lying down in fMRI machines, so she could watch how their brains responded. [TONGUE CLICKING] Salad bowl. [TONGUE CLICKING] Salad bowl in motion.

And then in a second study, she compared those readings to what happens in the brains of sighted people looking at the same kinds of things. Salad bowl. Salad bowl in motion.

Alix Spiegel

Very clever, very clever.

Lulu Miller

Yep. And what she found is that even though for decades scientists assumed that the visual cortex goes dark when you are blind, Daniel's was lighting up like a disco ball.

Lore Thaler

Yeah, so that was really very impressive.

Lulu Miller

And the way in which it was lighting up-- this is really cool. So it turns out that there are all these different parts of the brain involved in vision. So there's an area that's specifically dedicated to processing motion, and that's way over here behind the ears. And then there's a completely different area for texture--

Lore Thaler

Lightness, so how bright is something.

Lulu Miller

--orientation, shape. And in Daniel's brain, many of these areas were lighting up. Color and brightness, no action there. But motion, when they did that salad bowl in motion test, the motion area behind the ears started pumping with blood flow.

Lore Thaler

Very vigorously.

Lulu Miller

And orientation-- turns out there's sort of a grid for orientation in the brain. And she could watch as the salad bowl moved across those quadrants.

Lore Thaler

It was really robust, highly significant.

Lulu Miller

All right, Miss Spiegel. So I know that sometimes neurology and neuroscience--

Alix Spiegel

Goes over my head?

Lulu Miller

Or just sounds like a foreign language that you're not particularly interested in speaking.

Alix Spiegel

Uh-huh. Just land the plane for me. What does this mean?

Lulu Miller

What this work suggests is that you may not actually need eyes to see.

Lulu Miller

I kind of feel like we've got to shout it from the rooftops. Come on.

Alix Spiegel

Oh my god.

Lulu Miller

OK. You might not need eyes to see!

Now, Lore is by no means the only person seeing this result. The idea first started coming up in the mid '90s, when a lab at Harvard saw that visual areas of the brain can be activated by sound and touch.

Alix Spiegel

Do I have to do it?

Lulu Miller

Uh-huh.

Alix Spiegel

You might not need eyes to see!

Lulu Miller

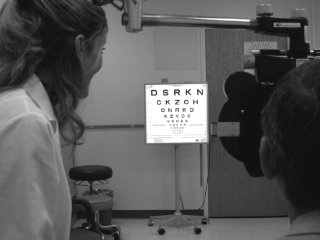

And since then, dozens of labs have been looking into just how nuanced and rich that visual imagery may be. So there's a guy at Berkeley, Santani Teng, who's been trying to determine the acuity of these images. You know, like an eye test-- how close to 20/20 are they?

Alix Spiegel

Uh-huh.

Lulu Miller

And what he's found is that their 75% localization thresholds indicated spatial acuity as fine as 1.5 degrees of the subtended angle.

Alix Spiegel

No!

Lulu Miller

It's true! I'll put it another way. He thinks their world looks a lot like your peripheral vision. So imagine that you're texting on your cellphone walking down the street. OK, you're looking at that screen. Now, what does the street look like to you?

You know, you can see people coming at you. You can see cars. You can see trees. But you couldn't read a sign. That, he thinks, is Daniel's world.

Daniel Kish

I can honestly, honestly say that I do not feel blind.

Alix Spiegel

So what does Lore say about this? Does she think that the echolocators are actually seeing?

Lulu Miller

Well--

Lore Thaler

That's almost philosophical, isn't it?

Lulu Miller

Lore asks the only people on Earth who can know-- people who use to see. You know, is what they're experiencing comparable?

Brian Bushway

Yeah, oh yeah.

Lulu Miller

This is Brian Bushway, who you met briefly at the top of the show.

Brian Bushway

So step right up!

I became totally blind at the age of 14.

Lulu Miller

But once he learned echolocation--

Brian Bushway

Just [SNAP] like that!

Lulu Miller

--the world around him, although blurrier and colorless, appeared again.

Brian Bushway

Things are real. I mean, it's as real as looking at it.

Alix Spiegel

Wait, wait, wait. So Lulu, does every blind person have this?

Lulu Miller

No. And that's the thing-- Lore has looked at the brains of people who do not echolocate, and though there's definitely some activity in the visual cortex, it's simply not as active. Which brings me back to Daniel's teaching methods. The thing about echolocation is, yes, you can learn it when you get older. But it gets so much harder with age, which is why Daniel doesn't give a damn about making a little kid cry, because he thinks at the other end of those tears is sight.

Daniel Kish

OK, off we go.

Lulu Miller

So I finally got to see one of these training sessions in action. We went to see a five-year-old boy named Nathan Nip.

Daniel Kish

OK, so what we'll do then is we'll ask Nathan's mom about parks or some place that he doesn't know.

Lulu Miller

Brian's with us too, actually. He's now one of Daniel's deputy teachers.

Daniel Kish

He can click.

Lulu Miller

And part of the goal that day was to get Nathan out of his comfort zone. But the bigger part-- and really, what is often this other major part of what Daniel is trying to teach-- is to get the people around Nathan to back off.

Daniel Kish

Hello?

Godmother

Hi!

Lulu Miller

So we go into the house.

Nathan Nip

I am five and a half, and Ashton's two.

Lulu Miller

Daniel asks to hear Nathan's clicks.

Nathan Nip

[TONGUE CLICKING]

Daniel Kish

You have a nice smiley click.

Lulu Miller

And then we head out to a faraway park.

Brian Bushway

Where are we? Where do you think we are?

Nathan Nip

At the field!

Brian Bushway

At the field.

Lulu Miller

Ding, ding, ding. It's a sports field flanked by a really busy road.

Brian Bushway

Nathan? Nathan?

Lulu Miller

And the idea is to make Nathan find his way around this park by himself.

Brian Bushway

So we want to use our, [TONGUE CLICKING], our clicks. And we're going to explore what's around here in this park. Let's see if we can find anything, OK?

Nathan Nip

Yeah.

Brian Bushway

OK.

Lulu Miller

So he finds a soccer net.

Brian Bushway

Yeah.

Lulu Miller

He tries to find a fence at one side of the park--

Brian Bushway

Well, you're-- yeah, we're in the bushes.

Lulu Miller

--but gets a little turned around.

Brian Bushway

Come back toward me. Nathan, come back toward me.

Lulu Miller

And then it's time to find the edge of the road.

Brian Bushway

What noises do we hear right now?

Nathan Nip

Cars?

Brian Bushway

Cars.

Lulu Miller

So Brian tells Nathan to walk toward those cars.

Brian Bushway

And we'll all follow behind you.

Lulu Miller

At this point, it's just me and the godmother and Brian.

Nathan Nip

Where's Ashton?

Brian Bushway

He's over there.

Lulu Miller

Everyone else is on the other side of the park.

Nathan Nip

Can we please go to him?

Brian Bushway

No.

Nathan Nip

Why?

Lulu Miller

Nathan is leading.

Brian Bushway

Can I hear you click?

Nathan Nip

[TONGUE CLICKING].

Lulu Miller

And picture this-- I mean, this is, like, a little five-year-old boy with a tiny white cane--

Alix Spiegel

Kind of tapping his way towards oncoming traffic?

Lulu Miller

Tapping his way toward oncoming traffic, which is a jarring sight. And the person closest to him is Brian, who is also blind.

Brian Bushway

Listen out in front of you. Listen into the distance.

Lulu Miller

And he's getting closer and closer to the edge of the road. Four feet, three feet, and then--

[CAR APPROACHING]

[SILENCE]

--his godmother just shoots out and grabs him back. And Brian kind of noticeably flinched.

Brian Bushway

Let's try to stay, like, more or less behind him.

Lulu Miller

Because while he completely understands why the godmother would reach out for Nathan, he said it is precisely that kind of moment that does the damage.

Brian Bushway

Often sighted people will jump in a half a second too soon, and they rob the blind student from that learning moment. And that just keeps happening over and over again, and I think so many blind people's lives, they never get that moment of what it is to really have that self-confidence to trust your senses to know, oh, if I do use my cane properly and I am listening attentively to information around me, I'll be OK.

Lulu Miller

I think part of the problem is that when we have eyes, we can see things coming from further away. The whole point is, like, when it's your cane and you're clicking, you catch edges at what appears like the last moment.

Brian Bushway

We don't need to go any farther. Why? Why don't we need to go any further?

Nathan Nip

'Cause there's cars.

Brian Bushway

Yeah, so it means the street's here.

Nathan Nip

[TONGUE CLICKING].

Alix Spiegel

Can I ask you a question?

Lulu Miller

Mm-hmm.

Alix Spiegel

What if you're a half-second too late?

Lulu Miller

Right.

Alix Spiegel

Because I think that probably a lot of parents-- I mean, the thing that keeps them reaching out well before the half-second before is kind of the specter of the half-second after.

Lulu Miller

So I think you grabbed him there.

Godmother

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Lulu Miller

And what was that moment like?

Well, this is exactly what Nathan's godmother brought up.

Godmother

It is hard.

Lulu Miller

She understands the dangers of a half-second too early.

Godmother

He has to learn how to make that judgment.

Lulu Miller

But at the end of the day, she is far more concerned about the dangers of the half-second too late.

Godmother

You don't really want to risk that.

Lulu Miller

Which brings me to possibly the biggest thing that Daniel is up against in his quest to change expectations-- love.

Daniel Norris

You can't blame mom and dad for struggling and wanting to keep their child safe.

Lulu Miller

This is Dan Norris again from the blindness organization in Vermont. And when we asked him if a change like the one Daniel's hoping for, a massive change in expectations, could actually take place, one of the main obstacles he brought up was love.

Daniel Norris

It's very hard as a parent with a child who's visually impaired to let go.

Lulu Miller

Even when the expectations for that kid are high, he said love can get in the way.

Daniel Norris

Those parents, they want to keep their child safe. They want their child to not suffer. And that's very noble but holds the kids back.

Lulu Miller

So in 10 years in the field, how many kids on bikes have you seen, blind kids on bikes?

Daniel Kish

Blind kids on bikes? I have seen about five.

Lulu Miller

That's actually pretty good.

Daniel Kish

Yeah, I think that we are seeing society begin to change.

Lulu Miller

But when he thinks about the sheer volume of love, brimming in every household on every schoolyard and every street corner--

Daniel Kish

Are we going to get there any time soon as a nation? Um, no. I don't think so.

Lulu Miller

And this gets us finally to what may have been Daniel's one true superpower.

Daniel Kish

What most people find to be the meaning of life absolutely creeps me out.

Lulu Miller

Daniel is 49 and has never been with a partner. And he finds the whole idea of physical intimacy--

Daniel Kish

Unsettling.

Lulu Miller

We had finally reached the end of our hike, the place Daniel wanted to take me.

Daniel Kish

Is this, like, awesome?

Lulu Miller

Yeah.

It was a huge old oak tree, miles from civilization, that Daniel said was one of his favorite spots on Earth.

Daniel Kish

OK.

Lulu Miller

And so we climbed up it together.

Daniel Kish

Let's see where I would go.

Lulu Miller

20 feet, 30 feet, maybe 40 feet.

Lulu Miller

You're very high!

And it was there in the branches that he told me he's never really been one for love.

Daniel Kish

I was never that interested in closeness as a kid. I wasn't really a lap-sitter. I didn't like holding hands. I didn't really like hugs.

Lulu Miller

He even used to have nightmares about it.

Daniel Kish

A child's mind will turn things into very ghoulish, ghastly, deeply unsettling, spooky things.

Lulu Miller

Like what? Like, what would be a nightmare about--

Daniel Kish

There were two.

Lulu Miller

In one, a hand chased after him.

Daniel Kish

And then the other thing were the plastic arms that want to sort engulf and unfold and just kind of take you in to themselves.

Lulu Miller

He's not sure where this comes from. He wonders if it could have been the surgeries he had as a tiny boy or from the way his parents raised him. Or maybe he just always was that way.

Daniel Kish

Who knows?

Lulu Miller

And while he's not suggesting that you need this quality to become independent, when he looks back, he wonders if this may have been one of the things that protected him from the debilitating effects of low expectations. Because unlike the rest of us, when those arms reached out for him, he never once had any desire to fall back into them.

Paulette Kish

Everything that happens in your life has its effect.

Lulu Miller

That's his mom again, Paulette.

Paulette Kish

Has its effect.

Lulu Miller

And you don't think it's that Daniel became this way because he was in some way neglected or because it was too hard? Is there any part of you that thinks you went too far in terms of letting him be?

Paulette Kish

No. No. He's happy.

Daniel Kish

Totally happy.

Lulu Miller

We sat there for a while, watching the afternoon slip away.

Daniel Kish

Listen to how quiet it is.

Lulu Miller

And suddenly I got that pang you get when you realize it's getting dark, and you are far, far from civilization. And that was followed by another pang that it literally didn't matter, because he'd be the one leading us out.

Daniel Kish

[TONGUE CLICKING] That's amazing.

Lulu Miller

Yeah.

Daniel Kish

[TONGUE CLICKING]

[MUSIC - "BATMAN THEME" BY NEIL HEFTI]

Ira Glass

Lulu Miller and Alix Spiegel of Invisibilia, the new public radio program and podcast. Lots of public radio stations, hundreds of them, have picked up the show. So check your local station's website to see if they might be carrying it and when. Or to get the podcast, go to npr.org/invisibilia.

Credits

Ira Glass

Our program was produced today by Sean Cole and myself, with Stefanie Foo, Chana Joffe-Walt, Sarah Koenig, Miki Meek, Jonathan Menjivar, Brian Reed, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp, and Nancy Updike. Our senior producer is Julie Snyder. NPR's Anne Gudenkauf is the editor in Invisibilia. She edited today's story. Production help today from JP Dukes and Simon Adler. Seth Lind is our operations director. Emily Condon's our production manager. Elise Bergerson's our office manager. Adrianne Mathiowetz runs our website. Elna Baker scouts stories for our show. Research help today from Christopher Swetala. Music help from Damien Graef.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

Our website, thisamericanlife.org. This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange. Thanks, as always, to our program's co-founder, Mr. Torey Malatia. He says, sure, yes, it's true. He was found wearing a bathing suit standing out in the middle of the street in the middle of winter, in the middle of night, holding a quarter million dollars in cash that was not his.

Paulette Kish

But that could happen to anyone. It can happen to anyone.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.