577: Something Only I Can See

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

When Jeffrey was 22 he had this rare problem with his eyes, and doctors had to use lasers to fix vessels that were bleeding at the back of his left eye which worked great. But not long after, on a cold, bright winter day, he came into his house from the cold and saw this color.

Jeffrey

And it was almost like an afterimage, like when you look at a bright light. And it was a blind spot right where they had put the lasers. And instead of seeing blackness, it was this greenish not-green. It was like a green that could never exist. And it was fluorescent. And it was kind of pulsating and staticky.

Ira Glass

Got that? Green, but not green.

Jeffrey

You know, actually maybe a better way of describing, it was like if the color black was fluorescent and green.

Ira Glass

Wait. I'm just going to say those words back to you. If the color black were fluorescent and green.

Jeffrey

Yeah.

Ira Glass

You know that sounds crazy, right?

Jeffrey

Yeah. Yeah.

Ira Glass

You know how some colors seem more energetic, like bright red or bright yellow, and others are more peaceful, like sort of a blue-green sea color? Which is this?

Jeffrey

It was both. It was both energetic and calming.

Ira Glass

But a lot of the color is greenish, right? It's in the kind of green family?

Jeffrey

Yeah, it is greenish. I remember I bought a bunch of markers a while ago trying to find a way of representing it to my doctor.

Ira Glass

And so if you were to try to paint it or draw it, you would start with a kind of fluorescent green, right?

Jeffrey

Mhm.

Ira Glass

And then what would you add to it to add the other part that is not green?

Jeffrey

Black and, like, fireworks.

Ira Glass

You just said black and fireworks?

Jeffrey

Yeah.

Ira Glass

He said that if you've ever had a migraine headache, it can come with a kind of colorful, sparkly static. It was like that. Fireworks. But really, he said, he's never done a good job describing this. How do you describe a color that only you have seen?

Ira Glass

OK, which of these things would you say about this color? Does it remind you of the feeling of punching somebody in the face, or more like a soft kiss from somebody who you're just falling in love with, or more like warm toast and butter on a cold morning?

Jeffrey

[CHUCKLING]

You know, I have to say, of those three options you give me, I think I only have lots of experience with the third.

Ira Glass

And does the color remind you of that one?

Jeffrey

You said warm toast and butter on a cold morning?

Ira Glass

Yeah.

Jeffrey

No.

Ira Glass

The color, does it remind you of the feeling of hope, or more a feeling of existential dread?

Jeffrey

Existential dread.

Ira Glass

The color, does it remind you at all of the feeling that you get when you're a kid and you get either a Ho-Ho or a Ding Dong, and it's sort of cool and so the outside shell of it is perfectly hard, and you bite into it and it cracks open and it's soft and chocolaty underneath?

Jeffrey

Um, no.

Ira Glass

The color, does it remind you of the feeling of somebody's going to cook something for you, and you don't really know if they're a good cook or bad cook, and then it turns out they're just an amazing cook. And everything you eat, you think, this is a very good version of this particular thing that I'm eating?

Jeffrey

Yeah, you know, Ira, it was a little bit more mundane than that.

Ira Glass

When you see something that nobody else can see, it can be terrifying. And Jeffrey was scared that maybe something was seriously deteriorating with his vision. But once it became clear that he was going to be fine and he was going to be able to see, he had this other impulse-- to show his friends. To share it.

Jeffrey

Well, yeah. I used to make drawings of it. I used to make drawings of the shapes. Like, I used a black pen and then I did the outline in that fluorescent. And you know, it's like, yeah, I'd show it to my friends and they didn't get it. They didn't think it was that neat.

Ira Glass

[LAUGHS] What would they say?

Jeffrey

Oh, man. Usually what I get is, "that's interesting."

Ira Glass

Ugh. That's the worst.

Jeffrey

Yeah.

Ira Glass

Of course, when you see something that other people can't, you're stuck. I think for most people, you want to tell somebody. You want to share it. You want to do something.

Today no our program, we have three stories of people in this exact situation-- one involving science, one involving comedy, one involving angels. These people see something nobody else can and they cannot stop themselves. They can't shut up about it.

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Stay with us.

Act One: Do These Genes Make Me Look Fatless?

Ira Glass

Act One, Do These Genes Make Me Look Fatless?

Well, let's kick things off with this story of somebody who not only sees something that nobody else sees, when she tells other people about the stuff she see, they don't buy it. Investigative reporter David Epstein explains.

David Epstein

I wrote a book called The Sports Gene. It's partly about how some super-athletes are genetically different from the rest of us. They have super genes. They're physiological freaks.

I was deluged with emails from parents wanting to know how they could find out if their child had Michael Jordan genes. A coach wrote offering up his players as guinea pigs for genetic experimentation. There were so many unhinged email coming in that I pretty much stopped opening them.

And then I got this one that had the subject heading, "Olympic Medalist and Muscular Dystrophy Patient with the Same Mutation" I opened it, figuring it would be a link to some article that I'd missed in my reporting. Instead, it was a note from a 39-year-old Iowa mother. Her name was Jill Viles. She was the muscular dystrophy patient, and she had a wild theory linking her genes to an Olympic sprinter named Priscilla Lopes-Schliep, and she wanted to send more info.

Sure, I said. Send it along. Why not?

Days later, a package arrived-- a 19-page illustrated bound packet. I thumbed through it. It was a little weird-- hand-drawn diagrams with cutouts of little cartoon weightlifters representing protein molecules, old photos of herself and her siblings, the original pictures, not copies. There was a detailed medical history, and it was clear she knew some serious science. She described in detail how proteins function. She referred to gene mutations by their specific DNA addresses, the way a scientist would.

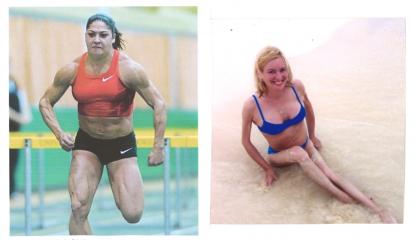

And then I landed on page 14. There were two photos-- one of Jill in a royal blue bikini, sitting on a beach. Her torso looks normal, but her arms, it's like they're on the wrong body, like the stick arms on a snowman. Her legs, too, are so thin that her knee joint is wider than her thigh. Those legs can't possibly hold her upright, I thought.

The other picture was of Priscilla Lopes-Schlip, who'd been ranked the best hurdler in the world. In 2008, she won the bronze medal in the 100-meter hurdles at the Olympics in Beijing. In the photo, she's in mid-stride. It's hard to describe just how muscular she looks. Picture all the muscle you can imagine on a woman. Now picture more.

In that photo, Priscilla's like the vision of a superhero that a third-grader might draw-- huge muscles bursting from her thighs, like her skin can barely contain all of the power beneath it; ropey veins snaking along her biceps. This is the woman Jill believed she shared the same genetic code with. Jill, remember, whose arms and legs are like sticks.

Announcer

But look at Lopes-Schlip. She's coming. Priscilla Lopes-Schliep making a move. To the finish she goes, and she will surge across that line. A world-leading time of 12:52.

David Epstein

All Jill's life, doctors had been mystified by her case. They had no idea how her muscle disease worked, much less how to treat it. She didn't know her disease came from a rare genetic mutation. And she wanted to reach Priscilla, because, looking at photos of Priscilla, seeing her body, she saw clues that made her believe Priscilla had the same mutation. If Priscilla did, if Jill was right, then scientists might figure out what was making Jill's muscles shrink and Priscilla's muscles balloon. And maybe people like Jill could someday be helped.

The whole thing seemed like a long shot, so I reached out to Robert Green, a geneticist at Harvard who I got to know while writing my book. He's an important proponent of people being allowed to get their own genetic tests. But after looking at the pictures of Jill and Priscilla, he thought Jill was almost certainly wrong. He doubted they had anything in common. And science aside, he had other concerns.

Robert Green

For one thing, a somewhat famous athlete, just like any other celebrity, can become the focal point for an individual for various reasons in a very unhealthy way. I was concerned that empowering a relationship between these two women could end badly, yeah. I mean, people go off the deep end when they're relating to celebrities they think they have a connection to.

David Epstein

Of course, this is a very polite way of saying, maybe she's a nut job. I wondered the same thing. How could you not? The idea that an Iowa housewife working off Google Images would make a medical discovery about a professional athlete, whose body has been obsessively examined for years by a small army of doctors and athletic trainers, it seemed pretty ludicrous. But the fact is people with MDs and PhDs have been telling Jill that her theories are ludicrous pretty much her whole life.

Jill was born in 1974. At first, everything was great. She met all the normal baby milestones. She sat, crawled, and walked on time. Then at age four, she started stumbling and tripping all the time, constantly falling flat on her face.

Jill Viles

I would describe this fear I had about witches' fingers.

David Epstein

This is Jill.

Jill Viles

And my mom was kind of puzzled. What was I talking about, witches' fingers? What do you mean? And when we'd walk, I'd felt this sensation, almost like there were little-- there were gnarled hands and fingers reaching up and grabbing my shins, and I'd fall really forcefully. That was kind of the beginning of noticing something was different.

David Epstein

Jill's dad remembered that he'd had some problems walking around the same age, which his doctors had said was the result of a very mild case of polio. But Jill's troubles were much worse than her dad's had ever been. And no one could give them an answer.

Her pediatrician was stumped. He suggested they take her to the Mayo Clinic. They were stumped there, too. They tested the whole family, and found that Jill and her brother and her dad all had signs of muscle damage. But Jill was the only one having trouble walking. It might be muscular dystrophy, the doctors thought, but that didn't usually show up this way in little girls.

Jill Viles

They were really, really sure they'd never seen anything like this. They said our family was extremely unique. And they couldn't define what type it was. Ultimately, that's good in one way because they're being honest.

But on the other hand, it was terrifying. What is my life expectancy? What are the symptoms that I'll be dealing with? It's alarming if you don't have something to grasp a hold of.

David Epstein

Jill went back to the Mayo Clinic every year, and it was always the same. There was nothing the doctors could do, nothing new they could tell her. The constant falling eventually stopped, but it was replaced by a burning sensation in her legs. And while she was growing in height like a normal girl, the fat on her arms and legs was vanishing.

By the time she was eight, her arms and legs were so skinny that other kids could wrap their fingers around her wrists and ankles. By age 12, veins were popping out of her legs. Kids asked how it felt to be old. And then her muscles started to fail again.

Jill Viles

I could remember just getting on a bike I'd always ridden and feeling like someone came up behind me and just threw me into the handlebars, and got a big bruise across my chest from-- I'd fall so hard. I couldn't hold myself over the bike. My muscles would just start quivering.

And roller skating-- I invited a friend to go with me, and I can't even stand up on the skates. And I'm just sitting there going, something's terribly wrong.

David Epstein

How rapid? How quick was that, that you basically lost the ability to roller skate and ride your bike?

Jill Viles

I would say probably within a few weeks.

David Epstein

Jill didn't even bother to tell her parents what was happening. She knew there was nothing there the doctors could do about it. By the end of that summer, the symptoms eased up. She could walk OK again. She started looking for answers on her own, but she did it the way a kid would.

Jill Viles

You know, I'm having my body do things that I can't control. Forces are acting on me. And I developed curiosity, fascination with things, like I would read about poltergeists. And I would bring home lots of books from the library. I remember it really freaked out my dad at one point, because he tipped over my book bag and there's all these books about supernatural things. And he was like, what are you into the occult or what? And it was nothing of the sort.

It was about, I couldn't explain what was going on with me. The doctors couldn't explain. And I found these people that people couldn't explain what was happening to them totally fascinating. I believe them.

David Epstein

By the time she went to college, Jill had maxed out at 5'3" and about 87 pounds. She decided that if she was going to figure out what was happening with her body, she'd have to do it herself. So during Jill's first semester, she set up camp in the library. She began poring over every textbook and scientific journal article she could find on different kinds of muscle disease.

Jill Viles

So I just thought, well, I'll start reading about them one by one and see if something fits.

David Epstein

She did this for months, going article by article, like a police officer driving up and down every street doing a grid search. But nothing really fit, until she came to a page in a medical journal about an extremely rare type of muscular dystrophy called Emery-Dreifuss.

Jill Viles

And then looking at the pictures, it was a very startling thing to realize, I'm seeing my dad's arm-- just an instantaneous lock on something that's in your visual memory.

David Epstein

Well, what did you see?

Jill Viles

As a little girl, I would notice he had what I called Popeye arms-- big forearms and hand muscles. And then as I'm reading about Emery-Dreifuss, they actually describe the look of the arms as a Popeye-arm deformity. But there were very, very few photos of women with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy.

David Epstein

The journal described the three hallmarks of Emery-Dreifuss patients. They couldn't touch their chins to their chests, or their heels to the floor, and their arms were perpetually bent at the elbow.

Jill Viles

And I'm getting chills reading this, thinking, well, I've got all three. A really great visual to think about that is, shockingly, a Barbie doll.

David Epstein

That is, elbows that don't bend and feet slanted to fit into high heels.

Jill Viles

Actually, it's a terrific representation of what does Emery-Dreifuss look like, which is very ironic because we give this to little girls and say, this is perfect. And we're actually handing them a doll that has a genetic disorder.

David Epstein

So when you flip open and you see these pictures and see these descriptions, is it like the light bulb just flipped on and this is it?

Jill Viles

The light bulb. I was sure. It's eerie. It's great, but it's terrifying. What was very frightening was to read there's a lot of cardiac issues involved with this disease.

David Epstein

Emery-Dreifuss patients, Jill learned, often dropped dead of heart failure. She became obsessed with reading about it. Before she went home for college break, she stuffed her bag full of medical books and journal articles.

Jill Viles

I purposely even hid them under several books because I didn't want to alarm anybody at home. And I went out in the kitchen long enough to make microwave popcorn. And I came back in and my dad was reading them. And I tried to take them away. And I'm like, just don't read those. And he was really sucked into it. And he said, well, I have all these symptoms. And I said, well, yeah. I know the arm thing and the neck. And he said, no. He said, I have all these cardiac symptoms.

David Epstein

He had always thought the stiffness in his muscles and heart troubles were unrelated.

Jill Viles

He said, well, the doctors told me I had a virus, not to worry about it. We both just looked to each other, and I said, it's not a virus. We have Emery-Dreifuss.

David Epstein

They went to the Iowa Heart Center, where doctors put a heart monitor on Jill's father. His pulse rate dropped below 30 beats per minute, which meant he was either about to win the Tour de France, or he was about to drop dead. He had a pacemaker put in immediately.

Mary Viles

She saved her dad's life. I mean, just absolutely amazing.

David Epstein

This is Jill's mom, Mary.

Mary Viles

If it wasn't for her, how would we have ever known this? I remember being in the hospital that day. And I think he was just in awe of Jill and just love, total love for Jill. But I think it was a hard burden for her, because it just seemed like no one else was looking.

David Epstein

The Iowa Heart Center wasn't set up to confirm whether or not her family had Emery-Dreifuss. That wasn't their specialty. So she went looking for someone who could. Remember, she was 19.

Jill Viles

Well, I went to a neurology clinic. I can remember even what I wore that day. I dressed up as professional as I could. I wanted to be taken seriously. I mean, I had on a navy pantsuit, and tried to present the articles to my neurologist.

David Epstein

And how did you even start that conversation? How'd you make your case?

Jill Viles

I just said I had been studying genetics. I've been spending a great deal of time in the library, and I've come across these photos. And I am sure this is what we have, and this is the name. And could you look at these with me? And the doctor just was very abrupt with me and said, no, you don't have that, and refused to look at the papers.

David Epstein

It might seem rude that a doctor would refuse even to look, but at the time, most doctors believed Emery-Dreifuss only occurred in men. Also, this was a self-diagnosis coming from a teenager-- a defiant teenager.

Jill Viles

There was times that, when I was in the doctor's office, I would see my chart, and it would just list, diagnosis muscular dystrophy, unknown etiology. I hated seeing that. I'd literally just take a pen out of my purse and I'd scratch it out and I'd write, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. And my mom would see me do that. And she's like, you can't change your chart! I want it listed what I have.

David Epstein

In a reading binge, Jill had come across a group of researchers working out of Italy. They were looking for families with Emery-Dreifuss to study, hoping to locate the gene that causes the disease. Jill decided to write to them. She mapped out a family tree, noting the symptoms she saw in her father, two younger brothers, and a younger sister. Then she stripped down to her underwear.

Jill Viles

And then I set the timer on my camera and I took pictures of myself, because I thought, well, if that's how I identified it, let me send a picture. And just inquired, would you want to take a look at our family?

David Epstein

Up to this point, the Italians had only collected four other families to study, so they were thrilled to hear from Jill and they immediately wrote back. From the letter, it seems like they think she's a scientist who has access to a lab. They asked, can you send us DNA? If you cannot prepare DNA, just send fresh blood.

But 19-year-old Jill soon learned you can't just go to the local hospital and say draw my blood. I want to send it to Europe. So Jill convinced a nurse friend to smuggle needles and test tubes to her house. They filled them up with samples of her family's blood and shipped them off to Italy.

Today, you can sequence an entire genome in a few days. But back in the mid-1990s, not so much. It was four years before Jill heard something definitive back from the Italians. They confirmed she had Emery-Dreifuss. She'd been right all these years, despite everyone telling her otherwise.

Jill Viles

One day, I opened email, and there it was. And that was a weird feeling to realize, OK, this is it. And I clicked on it, and they told me the name of the gene. It was nuclear lamin.

David Epstein

The researchers had discovered the genetic cause of Jill's illness, a gene called the lamin gene. What makes the lamin gene really important is that it affects the command center inside every cell in your body. This turns other genes on and off like light switches, changing the way they build fat and muscle.

Jill's lamin gene has a typo in it, a serious one. Along the spiraling ladders of her DNA-- the 3 billion Gs, Ts, As, and Cs that make up Jill's genome-- she had one letter in the wrong place.

Jill Viles

And it's just almost darkly comical to think, seriously? In this quest to find, OK, well, what happened exactly, it comes down to a G was changed to a C.

David Epstein

Soon after, Jill got an internship in a lab at Johns Hopkins that was mapping diseases associated with the lamin gene . The lab director had heard about Jill's research on herself and saw a chance to have not only a dogged intern in the lab, but also their very own real-life lamin mutant.

Jill's job was to sift through scientific journals and find any references that had been linked to a lamin mutation. Sitting there day after day reading, she came across an incredibly rare disease, a disorder called partial lipodystrophy. It causes the arms and legs to look as if all the fat on them has been melted away, leaving veins and muscle to stand out.

Looking at photos of patients with the disease, all Jill could think was that these people looked like her family members. Could Jill and her family have not just one, but two rare genetic diseases? The odds of getting one of them was one in a million. The odds of getting the other is one in at least a million. And the odds of getting both together? There haven't been enough human beings in the history of our species that anyone should ever get both.

So just like before, when Jill discovered Emery-Dreifuss, she zeroed in on a photo in a medical article and saw herself in it. And just like before, she tried to get confirmation from doctors. She tried to tell scientists that she had the second rare disorder, partial lipodystrophy. And just like before, they said no. They said that statistically there was very little chance that could be true. Instead, they diagnosed her with something a little more common.

Jill Viles

They didn't necessarily laugh at me but were kind of incredulous that, no, you don't have that. And they even kind of described it as intern syndrome, where you have a medical student that's being introduced to a lot of new diseases and they keep thinking they have what they're reading about.

I just thought, well, I must be wrong. I think I, too, was buying into that idea that that's quite a reach to think that you have the second genetic disorder, because it's so rare, too. I just kind of thought, well, maybe I am nuts. So I kind of backed away from that, even though it was kind of a deja vu feeling.

David Epstein

So she dropped it. She stopped reading about this new disease. And before long, she stopped doing research into Emery-Dreifuss, too, mostly because the research she was doing started to freak her out. In the case studies she read, the average person with Emery-Dreifuss was dead by their early 40s. She was 25, and anxiety over this was landing her in the hospital.

Jill Viles

I had two panic attacks that were brought on by the stress of reading all of these things-- that they just died suddenly. And I went to a counselor for a while. I worked with my cardiologist. And we decided it was just too much information. It wasn't healthy. So I really just didn't look up things, didn't read articles. And I really got to the point that I decided I want to go on with my old life.

David Epstein

So she went cold turkey. No more medical research, no more DIY diagnosis. She took a job as a writing instructor at local community colleges, and taught adult education classes at night. She started dating, eventually meeting the man who would become her husband. And even though there was a 50/50 chance that she would pass on the Emery-Dreifuss gene mutation, they decided to have a child.

Her pregnancy was normal, and her baby, Martin, doesn't have the disease. But after he was born, Jill really deteriorated physically. If you've ever had a muscle twitch, you know how strange it feels to not have control of your body. Jill's muscles started twitching from head to toe, sometimes for hours at a time, and she was suddenly having to hold onto her husband to steady herself.

Jill Viles

The best way I can describe what it was like, it would be like where gravity is getting incredibly heavy and someone turns up the knob. And you think of how high would they have to turn up this gravity that I can't get up off the floor by myself, I can't stand upright, I can't take a step? You know, it's a tremendous amount of force pushing on the body.

David Epstein

By Martin's first birthday, she could barely walk.

Jill Viles

One day, he was calling that he wanted macaroni and cheese. And I knew-- I had like six steps to take. And I realized, this is it. This is the last six steps I'm going to take. I just knew I was at that point that I was going to not be able to get up again.

David Epstein

At the same time, Jill's father was also losing his ability to walk. So father and daughter transitioned to life in motorized scooters. Jill says her dad was discouraged for the first time in his life. After a visit with a neurologist, he told her, I feel like I go there just to be weighed. Then one day, she got a call from her mom, and it was about Dad.

Jill Viles

He just moved from his scooter into his favorite chair. He said to my mom he just felt tired, and then he'd simply just bowed his head and he didn't breathe again and he died. He had a sudden cardiac death.

David Epstein

At what age was that?

Jill Viles

He was 63.

David Epstein

On the day he passed away, Jill and her siblings and relatives gathered at her parents' house.

Jill Viles

After most of the people had gone, it was kind of slowing down. And my sister said, I got this to show you. She starts pulling up pictures of this extremely muscular athlete. And I just took one look at it and just kind of went, we don't-- what? We don't have that. I mean, what are you talking about?

David Epstein

This, of course, was Priscilla. At first, Jill didn't get it, didn't see any connection with the musclebound athlete. It had been 12 years since she went cold turkey on medical research.

But a week later, Jill got curious. She started googling pictures of Priscilla-- not just running photos, but shots of her at home doing regular things, like feeding her daughter baby food.

Jill Viles

It helped seeing the clothing on her to see how it fit. It was just unmistakable. It's like a computer that could analyze a photograph and get a match, and be 100% sure that's the same shoulder. That's the same upper arm. I see the same veins. I see them branching this way. You just know. And that's hard to convey. How could you just know? But I knew we were very likely cut from the same cloth-- a very, very, very rare cloth.

David Epstein

It was the third time Jill saw something in a photo other people didn't see. It had happened with Emery-Dreifuss. It happened with lipodystrophy. Now she saw that she and Priscilla were both missing fat in the same places on their arms and legs. They had the exact same muscle divisions in the exact same places in the hips and butt. Jill was certain this was because they shared a mutant gene. And the only question was, why did the gene blow up Priscilla with muscles and take Jill's away?

Jill Viles

This is my kryptonite, but it's her rocket fuel. I mean, we're like comic book superheroes that are just as divergent as could be. I mean, her body has found a way around it somehow.

David Epstein

I know that sounds like the plot of a Hollywood movie. In fact, it's totally the plot of Unbreakable, The Bruce Willis, Samuel L Jackson film. Jackson plays a broken-boned, physically fragile man searching for his genetic opposite, a man born so strong his body will survive any physical trauma. In the final scene, Jackson tells Willis that he's the guy.

Samuel L Jackson

It all makes sense. In a comic, you know how you can tell who the arch-villain's going to be? He's the exact opposite of the hero.

David Epstein

So Jill wanted to enlist Priscilla in her genetic detective work, but there was a practical problem. She had no idea how to go about reaching her.

Jill Viles

I mean, I had crazy ideas, like can I fly to Canada and show up at a meet-and-greet and try to talk to her? And if you're on this motorized scooter, it's like, you're just going into end up with a restraining order at best. I mean, people will think you're crazy. I was just trying to resign myself to the fact that, well, what am I going to do?

David Epstein

A full year passed. And then Jill happened to be in earshot of her television when I started yammering about athletes and genetics on Good Morning America.

David Epstein

Find the best fit for your unique genome, and then specialize in the--

Jill Viles

And I thought, oh, this is just divine providence. This is exactly what I'm looking for.

David Epstein

Jill reached out to me with her request, and I did happen to have a way to get it to Priscilla-- through her agent.

Priscilla Lopes-schliep

It was such an odd request. It's just really out there, right?

David Epstein

This, of course, is Priscilla.

Priscilla Lopes-schliep

He was just like, this lady, she's in Iowa. She says she has the same gene as you and wants to have a conversation. I was kind of like, oh, I don't know, Kris. And he's just, have a conversation. See where it goes.

David Epstein

Jill sent Priscilla the same bound packet that she sent me. And it wasn't any of the cryptic science that got to Priscilla. It was the childhood stories Jill shared about kids pointing at the veins in her legs. Priscilla said she always used to come home sad and crying. She'd ask her parents--

Priscilla Lopes-schliep

Can I get the veins removed from my legs, because the boys are making fun of me? It was just like, ew, your legs are veiny. Ew, why does it look like that?

David Epstein

Once she grew up, the finger-pointing didn't end. It just morphed. When people see huge, shredded muscles like Priscilla's on an athlete, it usually means one thing-- steroids. And Priscilla's been dogged by doping rumors since college. After she won the Olympic bronze medal in Beijing, some media outlets in Europe began to openly accuse her. And of course, there were the not-so-furtive glances.

Priscilla Lopes-schliep

You'd walk by and people kind of like would whisper, like, oh, look at her glutes, or look at her arms or her shoulders or her calves. And just like, ooh, look, look, look. It's more like on the intern-- I remember there was one picture that was put up. They put a big dude's face on my body and he was just like, [GROWLING], like, I'm lifting-- because I'm running and pushing towards the finish line, so I'm using every ounce, every inch, every piece of energy in my body to get to that finish line.

That was pretty messed up. And I was really pissed about that. And I got tested. I felt like I was targeted, because I got tested so much for track and field. And I think a lot of people really, honestly, truly believed that I was taking steroids.

David Epstein

At the world championships in Berlin in 2009, Priscilla was drug-tested just minutes before winning a silver medal. There's not even supposed to be any drug testing that close to the race. Then the following month, at a meet-and-greet, someone stole her training journal out of her bag. It was at the very bottom, underneath expensive workout clothes and shoes, none of which were taken. Why steal a training journal? As someone who's covered a lot of doping stories, I'm convinced someone thought the journal contained her steroid regimen.

Priscilla and Jill spent a lot of time talking on the phone. And eight months after I first put them in touch, they finally met in person in Toronto, where Priscilla lived. They picked a hotel lobby. Jill arrived first.

Jill Viles

So it got to be a few minutes past the time we were going to meet, and then a couple more minutes. And I started to get really scared, because I'm like, I have so much riding on this. I was just watching the doors like, OK, is this her? Is this her? I wasn't sure. And I see this lady that, oh, my gosh, this is like seeing family.

David Epstein

Priscilla felt the same way.

Priscilla Lopes-schliep

It really was just like a wow moment-- like "do I know you?" kind of thing. So then we started talking, just giggling about it, like, OK, I'm going to flex for you. And then it's a little harder for her to get her sweater off, so she's pulling her sweater off to show me. She's like, see? I do have the definition, too. I'm like, you do. You do. But she's like, but it's a lot smaller than yours. And then we'd kind of giggle.

But it was still like, OK, there's something real. There's something here. Let's research and let's find out because how could the gene do this to you and do this to me? That was where my question was. I'm like, how?

David Epstein

It took a year to find a doctor to test Priscilla. Finally, Jill went to a medical conference and approached the foremost expert in lipodystrophy, Dr. Abhimanyu Garg, who runs a lab at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. He agreed to do the testing.

The results showed that Jill had been right. She and Priscilla do have a genetic connection. They each have a single typo on the same one of our 23,000 genes, the lamin gene. It's not the exact same typo, but they're almost right next to each other. That splinter of distance and typo location makes the difference between Jill's muscles and Priscilla's muscles. It's why Jill has Emery-Dreifuss and Priscilla doesn't.

But Dr. Garg also found that they do share a disease. They both have the exact same rare subtype of lipodystrophy, the disease that wastes away fat. Jill had been told it had nothing to do with her back when she was a summer intern at Johns Hopkins. Jill had been right about that all along. Dr. Garg called Priscilla immediately to give her the news. He caught her at the mall shopping with her kids.

Priscilla Lopes-schliep

I was just dreaming about going and getting a big juicy burger and fries. And Dr. Garg calls me and says, I have your results. I'm like, OK. And then I was like, can I call you back, because I'm in the mall right now? He goes, um, no, it's kind of important. Are you about to go eat lunch? And I was like, yes. He's like, you're only allowed to have salad. You're on track for a pancreatitis attack. And I was like, say what?

David Epstein

Then he told Priscilla that, despite her rigorous training regimen, her untreated lipodystrophy left her with 15 times the normal amount of fat in her blood. Her next hamburger could land her in the emergency room. She was that close.

In other words, once again, Jill steered someone away from a medical disaster. She'd saved her dad's life. Now, using the cutting-edge medical tool known as Google Images, she caused the most intense medical intervention in the life of this professional athlete.

Priscilla Lopes-schliep

That's when I was just like, oh, my gosh. If this wasn't for Jill, I would definitely have been in the hospital. And I called her and I told her. I was like, you pretty much just saved me from having to go to the hospital. And she goes, what? I go, Dr. Garg told me that I have the gene and my numbers are out of the roof.

David Epstein

Scientists can learn all sorts of things by studying very rare genetic diseases. For instance, research on a rare gene mutation that gives people freakishly low cholesterol levels led to a drug that treats high cholesterol. An Alzheimer's treatment might come from studying a small group of people in Iceland. They have a super-rare mutation that protects their brains.

Recently, a group of scientists started something called the Matchmaker Exchange. It's a kind of OkCupid for rare diseases, where people can share genetic and symptom information with each other and doctors. The hope is that it will spark new discoveries.

Etienne Lefai

It's just the willpower of Jill that have made things possible.

David Epstein

That's Etienne Lefai, a molecular biologist in France. He does super-technical work on a protein with the lovely name SREBP-1. It affects fat storage. And his research team showed that messing around with it can create mice with almost no muscle at all, or potentially little rodent Schwarzeneggers. When Jill first reached him, she told him that he may have found the actual biological mechanism that makes her and Priscilla so different.

Etienne Lefai

OK, that triggers a kind of reflection from my side, saying, that's a really good question. That's a really, really good question, because I have no idea of what I can do with genetic diseases before she contacted me. Now I have changed the path of my team, research object. And this is only because Jill contacted me two years ago. She's totally awesome.

David Epstein

And have you ever had the experience of someone outside the scientific community affecting your research agenda in this kind of way?

Etienne Lefai

In my life, no. People from outside coming and giving me hopes, new ideas-- I have no other example of these kind of things. You know, maybe it happens once in a scientific life.

David Epstein

Of course, this is so different than the skepticism Jill's gotten from scientists and doctors for decades. I checked back in with one of the doubters, Robert Green-- you know, the geneticist at Harvard I first talked to who was so incredulous about any genetic connection between Jill and Priscilla. I email him the results of Priscilla's genetic test.

Robert Green

Oh, I was knocked over. I was completely and utterly astounded. And I remember thinking I was ashamed that I had doubted this individual because she turned out to have a remarkable discovery.

David Epstein

About a week after I talked to Doctors Green and Lefai, I played those conversations back for Jill

Jill Viles

[CRYING]

David Epstein

Could you hear that OK?

Jill Viles

Yeah, I could hear that.

David Epstein

So what's in your mind when you hear that?

Jill Viles

It really does feel really good. Wow. It's kind of like this weight come off of me. So I'm exhausted emotionally and intellectually, and in every way possible. I am so happy. I don't want to be the crazy person that's on the internet all the time coming in. I really feel confident we can go somewhere with this. And I've got some really great people.

David Epstein

Jill says she's proved her point. She says she's retiring from DIY medical research. She gave me the same line that professional athletes use. "I want to spend more time with my family." But her mother doesn't believe she's retiring, nor does Dr. Lefai. And I certainly don't believe her.

Recently, Jill sent me an email. She picked up on a tidbit in a very technical scientific paper about potentially reversing muscular dystrophy. "I don't want to read too much into this," she wrote me, "but, of course, I'm curious."

Ira Glass

David Epstein. The book that he wrote that kicked all this off is The Sports Gene-- Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance. He has more about Jill and Priscilla, including jaw-dropping photos, at propublica.org.

In the years since we first ran this story, as predicted, Jill has gone back to the research game. She still talks to Priscilla, who recently retired from track and field.

Coming up. OK, you know how we started today's program with the color green that was not green? After the break, Tig Notaro finds a joke that is also not a joke. That's from WBEZ Chicago when our program continues.

Support for This American Life comes from Squarespace, the all-in-one platform that lets you create a beautiful website or online store. A wide range of people and businesses use Squarespace-- musicians, designers, artists, restaurants, and more, all taking advantage of Squarespace's award-winning templates and award-winning 24/7 customer support. There's nothing to install, patch, or upgrade ever. To start your free trial and receive a special offer on your first purchase, go to squarespace.com/american. Squarespace, make your next move.

And from Rocket Mortgage by Quicken Loans. When it comes to the big decision of choosing a mortgage lender, work with one that aims to protect your best interests. Rocket Mortgage provides a transparent online process that helps you understand all the details of your home loan. You can even adjust the rate and length of your loan in real time to make sure you get the right mortgage solution for you. Skip the bank, skip the waiting, and go completely online at quickenloans.com/american. Equal housing lender licensed in all 50 states. NMLSConsumerAccess.org, number 3030.

Act Two: Mom Jokes

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose a theme, bring you different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's show, "Something Only I Can See." We have stories of people who spot something that no one else has noticed and then feel compelled to tell somebody, show somebody, do something about it.

We've arrived at Act Two of our program. Act Two, Mom Jokes.

So comedians don't usually laugh at their own jokes as a rule. It's gauche. It makes things less funny as a rule. But, as Van Halen once said, "rules are for fools." Tig Notaro has been on our program before. She talked to Nancy Updike about a recent rule-breaking addition to one of her stand-up shows.

Nancy Updike

As we know, 58% of all important events in America start in the car. Tig and her fiancee Stephanie were driving along with--

Tig Notaro

Her mother, her sister, my stepfather, and my brother. And we were in New Orleans. And--

Nancy Updike

This is a big car.

Tig Notaro

Yeah, we had an SUV. And my fiancee, her mother was telling us this joke that she had come up with. And in trying to tell the joke that she had made up, she was laughing so hard she couldn't get the joke out.

Nancy Updike

This went on for a couple of minutes-- laughing, catching her breath, almost starting to tell the joke, and then more uncontrollable laughing, until everyone in the car was laughing just watching her trying to tell the joke.

Tig Notaro

I don't know that I've ever written a joke this funny. This is like--

Nancy Updike

Right. This is my job and I have never made somebody laugh as hard as you are making your own self laugh.

Tig Notaro

Exactly. It's just like, come on, Carol. What is this joke?

Nancy Updike

And then Tig had a vision of what needed to happen at her next stand-up show.

Tig Notaro

It became very apparent to me. I just thought, oh, my gosh, I have to have her on my show to tell her joke, whatever it is.

Nancy Updike

Before she got to the joke? Before she even told the joke?

Tig Notaro

Oh, yeah.

Nancy Updike

Just while she was laughing?

Tig Notaro

Yeah. Oh, my gosh, immediately.

[APPLAUSE]

Oh, boy. Coming to the stage, please welcome my girlfriend's mother, Carol Ashton.

[ENTRANCE MUSIC]

Nancy Updike

Two weeks after the car ride, Tig made her vision come true. Carol walks onto the stage of a comedy club in Los Angeles called Largo. She's not in jeans. She's not in comedy club casual. She is a tasteful mom in cropped white pants carrying her purse. She is a civilian.

Tig Notaro

Yeah, how are you feeling?

Carol Ashton

Well, I can't really describe how I'm feeling, because I've never felt this emotion before. So I don't know what it is.

Tig Notaro

You just bummed everyone out, Carol.

Nancy Updike

Carol knew two things about her own joke when she walked onto the stage. She knew that it was not a very good joke. She told Tig when Tig was trying to convince her to come on stage. She said, this is nuts. Nobody's going to laugh. Carol also knew that she herself could not tell the joke without laughing. She was living the mystery many of us have lived-- the all-the-way-inside joke. The joke that is funny beyond reason in your head and you cannot communicate the funniness, because you don't even understand it. That's what Carol knew. So she was nervous.

Tig Notaro

Can you tell me how and when you thought of the joke?

Carol Ashton

OK. Well, first, I would feel a lot more comfortable--

Tig Notaro

If I left?

Carol Ashton

No. Actually, I would feel a lot less uncomfortable if--

Tig Notaro

If everyone left.

Carol Ashton

Yeah. But if you told them this was not my idea.

Tig Notaro

Oh, they know that one-- was there one person at all here tonight? Do not be shy. Raise your hand if you think Carol Ashton said, hey, Tig. It's Carol. I have got some stand-up that is going to blow your mind. Carol, I can't just put you on stage at Largo. Wait till you hear the joke, kid. Kid? Must be good.

Nobody here thinks that you asked to be here. Were you driving along and the idea came to you?

Carol Ashton

Yeah, I was driving alone, and I got this great idea. I thought, this is a very funny joke.

Tig Notaro

Which is why you're here tonight, Carol.

Carol Ashton

I'm here! First, I have to explain, though. It's kind of like--

Tig Notaro

OK. Go ahead. Set it up.

Carol Ashton

That it's like a play on words.

Tig Notaro

It's good to explain what genre the joke is. Don't let them figure it out. You tell them. Tell them, Carol.

Carol Ashton

Right. Well, Stephanie said, it's like that Lou Gehrig joke, where it's, gee, what are the odds of Lou Gehrig getting Lou Gehrig's disease? It's that kind of joke.

Tig Notaro

All right. We got the genre down.

Carol Ashton

So I'm driving along and it came to me about-- the only problem is it's about somebody that's not really in the news-- well, never really in the news, but in the public eye anymore.

Tig Notaro

OK. So it is out of date?

Carol Ashton

Yeah. It's out of date. That's the downside.

Tig Notaro

All right. So we got the genre. We've established that this is completely out-of-date material.

Carol Ashton

And so, since you're the comedian--

Tig Notaro

Not right now.

Nancy Updike

Of course, everything Carol is doing is usually comedy death-- explaining the joke, exposing the machinery of it-- and she is killing.

Carol Ashton

Should I say who the joke is about?

Tig Notaro

Well--

Carol Ashton

That's necessary, right?

Tig Notaro

It's your joke. I--

Carol Ashton

OK, so the joke is about Paris Hilton. See what I mean? Like, Paris Hilton's dead now. So yeah, it's about Paris Hilton. And so this is the joke. Who would name their kid--

[LAUGHING]

[APPLAUSE]

Tig Notaro

That is always part of the joke. She laughs at herself for two minutes.

Carol Ashton

I'm sorry.

Nancy Updike

Carol's rocking backward and slapping her knee, she's laughing so hard. She has spent the last 10 minutes giving caveats, laying out everything the joke has going against it, why it's no good. And then when the joke comes into her head, as she's about to tell it, none of that matters.

Carol Ashton

[LAUGHING]

Who would name their kid after a hotel chain?

[APPLAUSE]

I know who. The same people that would name their kid after a famous city in France. I think it's so funny.

Tig Notaro

No, I--

[LAUGHING]

Ladies and gentlemen, Carol Ashton.

[HOOTING AND HOLLERING]

Tig Notaro

I mean, when I got off stage that night, I don't know if it was Flanagan, the owner of Largo, but somebody was like, I think that was the biggest response that they'd ever heard in that room. It was almost like one of the biggest comedians in the world made a guest appearance on my show.

Nancy Updike

All jokes start as inside jokes, inside someone's head. Some of them make it out into the world and catch on, and that's comedy, the way it usually works. This was a rare chance to root for the other kind of joke-- the nonstarter, the crush no one understands, including you. Your rational brain can make its rational arguments, and then what? You stop having feelings you don't understand? No.

Ira Glass

Nancy Updike is one of the producers of our program. Tig Notaro's book, I'm Just a Person, came out last summer.

Act Three: Earth Angel

Ira Glass

Act Three, Earth Angel.

So we close today's program with this story about somebody who sees and believes something that nobody else does. From Etgar Keret, it's read for us by actor Alex Karpovsky.

Alex Karpovsky

On Bernadette Avenue, right next to the central bus station, there's a hole in the wall. There used to be an ATM there once, but it broke or something, or else nobody ever used it. So the people from the bank came in a pickup and took it and never brought it back. Somebody once told Udi that if you scream a wish into this hole, it comes true. But Udi didn't really buy that.

The truth is that once, on his way home from the movies, he screamed into the hole in the wall that he wanted Daphne Remalt to fall in love with him, and nothing happened. And once, when he was feeling really lonely, he screamed into the hole in the wall that he wanted to have an angel for a friend. And an angel really did show up right after that, but he was never much of a friend. And he'd always disappear just when Udi really needed him.

This angel was skinny and all stooped, and he wore a trench coat the whole time to hide his wings. People in the street were sure he was a hunchback. Sometimes when they were just the two of them, he'd take the coat off. Once, he even let Udi touch the feathers on his wings, but when there was anyone else in the room, he always kept it on. Kids asked him once what he had under his coat, and he said it was a backpack full of books that didn't belong to him and that he didn't want them to get wet.

Actually, he lied all the time. He told Udi such stories you could throw up-- about places in heaven; about people who, when they go to bed at night, leave the keys in the ignition; about cats who aren't afraid of anything and don't even know the meaning of scat. The stories he made up were something else. And to top it all, he'd cross-his-heart-and-hope-to-die.

Udi was nuts about him and always tried hard to believe him, even lent him some money a couple of times when he was hard up. As for the angel, he didn't do a thing to help Udi. He just talked and talked and talked, rambling off his harebrained stories. In the six years he knew him, Udi never saw him so much as rinse a glass.

When Udi was in the army in basic training and really needed someone to talk to, the angel suddenly disappeared on him for two solid months. Then he came back with an unshaven, don't-ask-what-happened face. So Udi didn't ask, and on Saturday they sat around on the roof in their underpants just taking in the sun and feeling low. Udi looked at the other rooftops with the cable hookups and the solar heaters and the sky. It occurred to him suddenly that, in all their years together, he'd never once seen the angel fly.

"How about flying around a little?" he said to the angel. "It would make you feel better."

And the angel said, "forget it. What if someone sees me?"

"Be a sport," Udi nagged. "Just a little. For my sake." But the angel just made this disgusting noise from the inside of his mouth and shot a gob of spit and white phlegm at the tar-covered roof.

"Never mind," Udi sulked. "I bet you don't know how to fly, anyway."

"Sure I do," the angel shot back. "I just don't want people to see me, that's all."

On the roof across the way they saw some kids throwing a water bomb. "You know," Udi smiled. "Once, when I was little, before I met you, I used to come up here a lot and throw water bombs on people in the street below. I'd aim them into the space between that awning and the other one," he explained, bending over the railing and pointing down at the narrow gap between the awning over the grocery store and the one over the shoe store. "People would look up, and all they'd see was the awning. They wouldn't know where it was coming from."

The angel got up too and looked down into the street. He opened his mouth to say something. Suddenly, Udi gave him a little shove from behind, and the angel lost his balance. Udi was just fooling around. He didn't really mean to hurt the angel, just to make him fly a little, for laughs. But the angel dropped the whole five floors, like a sack of potatoes. Stunned, Udi watched him lying there on the sidewalk below. His whole body was completely still, except the wings, that were still fluttering a little. That's when he finally understood that, of all the things the angel had told him, nothing was true. That he wasn't even an angel, just a liar with wings.

Ira Glass

Alex Karpovsky reading Etgar Keret's story, "Hole in the Wall," which is collected in his book of short stories called The Bus Driver Who Wanted to be God.

Credits

Ira Glass

Our program was produced today by Stephanie Foo with Zoe Chace, Sean Cole, Neil Drumming, Chana Joffe-Walt, Miki Meek, Jonathan Menjivar, Robyn Semien, Alyssa Shipp, and Nancy Updike. Our senior producer for today's show is Brian Reed. Editing help for today's show from Joel Lovell and Julie Snyder. Our technical director is Matt Tierney. Production help from Emmanuel Dzotsi and Diane Wu. Research help from Christopher Swetala and Lu Fong. Musical help today from Damien Graef and Rob Geddis.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

Jeff Emtman, who you heard at the beginning of our program-- the guy who saw a green that was not green-- is the host of Here Be Monsters, a podcast about fear and the unknown from KCRW. Our website, thisamericanlife.org. This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange.

Support for This American Life comes from Lagunitas Brewing Company, committed to keeping the pub in public radio by offering curious ales and lagers for those who appreciate hearing and telling great stories. Learn more at lagunitas.com.

Thanks, as always, to our program's co-founder Mr. Torey Malatia. You know, he and I were on a flight together this week and we got delayed on the tarmac for three hours. It got to the point where Torey started calling out to the cockpit and heckling the pilot.

Alex Karpovsky

How about flying around a little? It would make you feel better.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.