622: Who You Gonna Call?

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Sean Cole

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life.

[DIALING]

Ira Glass is off this week. I'm Sean Cole.

Pat

Yo, Sean! This is your mom. I wasn't home.

Sean Cole

I'm just going to say up front that today's show deals with a device invented more than a century ago to facilitate real time voice-to-voice interaction. The kids don't use it much for that purpose anymore, but in all the stories you're going to hear, the phone's primary purpose is as a phone.

About four or five years ago, I started saving all my mom's voicemails, thinking, she's not going to be around forever. I'm going to want to hear her voice when she's gone. Though somehow I didn't extend that thought to, "I could hear her voice right now if I picked up the phone." She had a talent for the form. With some of them, it almost feels like I'm talking to her, except she's playing both parts.

Pat

What time is it? Oh, it's 6:52. Yeah, it's later than I thought. I can't believe it's still light out. Decided to go to the Royal for supper tonight. So that's what we did. We went early, and we are back early. So I don't know what you're doing. So this is me, c'est moi. I'm here. Right. Yo aqui.

Sean Cole

C'est moi. It's me in French. Sometimes there's not much more than that.

Pat

C'est moi. Love you much. Talk to you soon. Bye.

Sean Cole

This one's even shorter.

Pat

C'est moi. Bye.

Sean Cole

But of course all the messages boil down to her saying, in one creative way or another, "Please call me back." Sometimes she was a lot more direct about it.

Pat

Don't forget to call your mother! Goodbye!

Sean Cole

Actually, here's the one that I always tell people about when I'm talking about her messages. It's like she sort of circles and then goes in for the kill.

Pat

I heard you on the radio on Sunday, and I knew it was you, because I could recognize your voice, even though it's been a long time since I've heard it on the phone. So anyway, I love you lots and lots. Call me when you think of it, if you ever do. Love you. Bye.

Sean Cole

My mom, her name was Pat. She died on September 28, 2015, At 4:22 in the morning. It was relatively sudden and totally unexpected. And as much as I thought I was preparing myself for that moment, I wasn't prepared. It's true, I didn't call enough. But she was still the first person I thought to call when something huge happened. Good or bad.

I loved talking to her. She was funny, as you can tell. And smart. She wrote technical manuals in the early days of personal computing. Later in life, she lugged a lot of pro-grade camera equipment around the world, taking pictures. And yet she had a hard time figuring out her smartphone. The last recording I have from her saved on my phone, it was a pocket dial.

[POCKET DIALING]

This goes on for three minutes.

Sean Cole

Did you go for your walk this morning?

Ed Hacker

No, I didn't make it this morning. I figured that I was pretty busy.

Sean Cole

After mom died, I started calling home a lot more to talk to my stepdad, Ed Hacker. He and I never really had a phone relationship when my mother was alive. It was more the classic thing of, "You wanna say hi to Ed?" And then we'd verbally clap each other on the back, and then back to mom. These days, it's not weird for us to spend almost two hours on the phone together.

Ed Hacker

Then I had to get tweets out, so--

Sean Cole

You are the most active octogenarian on Twitter that I know about.

Ed Hacker

Well, I try to send out about six or seven tweets.

Sean Cole

What did you send this morning?

Ed Hacker

Oh, I said about three or four.

Sean Cole

I think of how annoyed my mom would be if she knew this, but I'm now performing the exact telephone behavior she wanted from me when she was around, except now with Ed. I call about once a week on average. And it's always me initiating the calls now.

At first, of course, it was mainly to make sure he was holding up OK, and to make sure I was holding up OK. But even now, when I miss a week, it eats at me, like I'm thinking, "Gotta call Ed, gotta call Ed." It's like an injustice that he's getting this treatment and not her, and I keep trying to square it somehow. But when I put this to Ed, he basically said it's really not that big a mystery.

Ed Hacker

Kind of obvious that if one parent dies, you realize that the other one may not be that far off, that he will go too, or she. So you know, the scarcity, just like in economics, makes the value go up.

Sean Cole

I never thought of this in economic terms before.

Ed Hacker

Well, it's true of many things. If the population is very low--

Sean Cole

Ed's 87. He taught philosophy and logic at a university in Boston for a lot of years. Which is fitting, because Ed is very logical and philosophical. He's always quoting one or another great thinker. For fun, he does math. He and my mom got together when I was six. He moved in when I was 11. And I think he's right that I call because I'm more aware than ever that one day he won't be on the other end of the phone, but it's more than that too.

Even though we have all of these other people in our family, whom we love, it got to feeling like Ed's the other one mom's death happened to, like he and I were the ones who mutually needed to talk about mom, and to hear about her.

Ed Hacker

I feel that, yes, I could talk to you about Pat, because you're willing to talk to her about it.

Sean Cole

To you about it, yeah.

Ed Hacker

And it makes a big difference to me.

Sean Cole

It does?

Ed Hacker

Of course.

Sean Cole

I'm so glad to hear that.

Ed Hacker

Because you lost the same person. Even if it's somewhat similar if somebody else has lost someone else, you know, these groups in which everyone has lost a spouse, and their memories are different. You know you never met the other person that died. You really don't care.

[CHUCKLING]

You care about your loss. You know, be honest.

Sean Cole

Are you on the deck now?

Ed Hacker

I am.

Sean Cole

Having a smoke?

Ed Hacker

I am.

Sean Cole

For a long time, my mom was a third invisible person in all of these conversations. And it feels weird to say this, but in some ways, it's like I've gotten to know her better from talking to Ed. And I'm clearer now on what her very last days on earth were like. But we've both noticed we're talking about mom less and less.

People told me this would happen, but I didn't really believe them. Or I didn't want to. Time slouches on. You wake up to different thoughts in the morning. And when you call home the first thing you say isn't, "How are you holding up?" Like, it used to be that you would mark how long it had been. You'd say like, "I can't believe it'll be three months on Monday," or, "I can't believe it'll be nine months on Thursday or whatever."

Ed Hacker

Well, I still keep track of the time.

Sean Cole

You do?

Ed Hacker

Yeah, and I also have an app on my computer, all three of them, which is set to tell me how many days since Pat died.

Sean Cole

You do?

Ed Hacker

I do.

Sean Cole

Oh, I didn't know that.

Ed Hacker

So this way, I'm going there right now, to see what my apps are. What do they call it now? Got too much junk here.

[CHUCKLING]

Oh yes, Count Down. You can set it for anything, you know. I mean-- well, it's been 22 months and three days since she's died. Or if you want, one year, 10 months, and three days. Or if you want, 95-- 96 weeks.

Sean Cole

And what do you feel like, looking at that?

Ed Hacker

Don't have any particular feeling. It's just that it's amazing that it's almost two years. It's like saying I remember.

Sean Cole

Yeah, I feel like I need something like that. I just feel like I don't think about her enough.

Ed Hacker

Well, that you'll have to explain. Why should you think more?

Sean Cole

I don't know. It's just like--

Ed Hacker

Is it guilt or something?

Sean Cole

It's not guilt, no.

Ed Hacker

You want to honor her more by thinking about her?

Sean Cole

Yeah, I want to honor her more by thinking about her, and it also feels like there's something going on in me all the time that I'm not acknowledging, that kind of leaks out in these other ways. And I just miss her. And so it's like I need to put that missing somewhere.

Ed Hacker

Well, you have a photograph of Pat?

Sean Cole

Yeah, I have one up on the wall in my office.

Ed Hacker

OK, take another one. And every day, move it from one spot to another in your apartment.

Sean Cole

That's a really good idea. Did you just think of that?

Ed Hacker

Yes. That makes it sort of a ritual.

Sean Cole

But the truth is, I already have the ritual I need. I don't do it every day, but I do it just about every week. I call Ed. We talk. For this specific need I have, it turns out he's the perfect person to call. Maybe you've got somebody like that, a personal Ghostbuster when there's something strange in the neighborhood, when things are looking their worst, that person who will know what you're talking about, even if they can't understand what you're saying. And all you've gotta do is call.

Our show today in three area codes is about people lucky enough to find someone like that, in some very dire situations, and also when they need directions to Garbage Street. It's really called that. Stay with us.

Act One: Fass Talker

Sean Cole

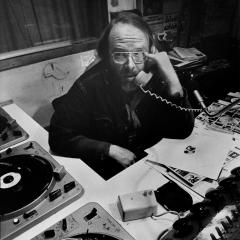

Act 1, Fass Talker. There's this legendary late night radio show host on WBAI here in New York named Bob Fass. And he hosts a show called Radio Unnameable. It first went on the air in 1963, and it was Bob's idea. He told the station managers he wanted to talk to all the late shift workers and the other night owls who were up at that hour.

Bob Fass

This is Bob Fass, and this is Radio Unnameable.

Sean Cole

He goes on at midnight, keeps listeners company until dawn. For a while, it aired five or six nights a week, but ultimately the station scaled it back to Thursday nights. WBAI is a listener-funded community station. It's part of the Pacifica Foundation. And when Radio Unnameable started, it was the kind of 1960s, 1970s radio show that really doesn't exist anymore. If Bob liked a song, he might play it over and over again all night. Or he'd play two songs at once.

Famous musicians like Bob Dylan would drop by after midnight. Sometimes, they performed. And sometimes, Bob would put a ton of people on the phone all at once.

Woman 1

There's snow out there.

Woman 2

Snow?

Woman 1

Snow.

Woman 2

Where.

Woman 1

Trees.

Sean Cole

This audio is from a documentary movie about Bob's show. The movie is also called Radio Unnameable.

Woman 2

Is there snow?

Woman 1

Yeah, there's snow.

Woman 2

Oh.

Woman 1

Where have you been?

Woman 2

Oh, wait a minute.

Woman 1

Open your eyes and look outside. There's snow.

Woman 2

Nope, not on 60th. It's as dry as a bone. Where are you?

Woman 1

I'm on 66th.

Woman 2

No snow on 60th. I swear it.

Woman 1

Must be an underprivileged street.

Sean Cole

A lot of people have felt like Bob Fass was the perfect person to call, when they were alone in the middle of the night.

Suicidal Caller

Bob, you just missed a good conversation.

Sean Cole

And the story I'm going to tell you is about just one caller for whom that was certainly true. This call came in to WBAI on November 6, 1971, about a quarter to 3:00 in the morning.

Bob Fass

BAI.

Suicidal Caller

Oh, it certainly takes you long enough.

Sean Cole

Bob and the caller talked for 45 minutes. This is minute one.

Suicidal Caller

Are you a gentlemen? I hope.

Bob Fass

I don't know what a gentleman means.

Suicidal Caller

Well, I'm in the process of committing suicide, and maybe this would help BAI, you know, to collect money or something.

Sean Cole

Just a quick trigger warning for people who are sensitive to hearing about suicide, that's what this call is about.

Suicidal Caller

But don't turn me in or ... my number or anything like that.

Bob Fass

You're in the process of committing suicide.

Man

That's a crime.

Sean Cole

That voice there is another guy who was in the studio with Bob that night. Even Bob doesn't remember who it was anymore. It was a long time ago.

Suicidal Caller

That's a what.

Sean Cole

And here Bob kind of shushes his friend.

Bob Fass

Don't answer that.

Suicidal Caller

A crime? All my life I've wanted to commit a crime. At last, I succeeded.

Bob Fass

Why? I mean, why did you call up to say that you were going to commit suicide?

Suicidal Caller

Because you might be able to use this in some way.

Bob Fass

How can I use it?

Suicidal Caller

I see it as an item on page 3 of tomorrow's New York Post, you know? "Suicide calls BA--."

Sean Cole

Apparently, the caller says a cussword at this point. They had to censor it.

Bob Fass

All right. Hey, that's really funny. Like, you say you're going to commit suicide, and now I have to bleep you off the air.

Suicidal Caller

How do you mean, "Off the air?"

Bob Fass

Well, you said you said a word that you can't say on the air, even if you are about to depart this vale of tears.

Suicidal Caller

I am.

Bob Fass

You are, huh? Why? I mean--

Suicidal Caller

... of things, including a final rejection from a girlfriend, trite as all that.

Bob Fass

Well, that'll really teach her, won't it?

Suicidal Caller

Teach her or me?

Bob Fass

Her. Well, it'll teach you, I guess.

Suicidal Caller

Teach me. Yeah, she'll be around for a while.

Sean Cole

If you listen closely, you can hear a sort of hushed hubbub in the background. Bob's writing a note to get people's attention. It wasn't long before other staff at the station were calling the police, who in turn started working with the phone company to see if they could track the guy down. All the while, Bob stays surprisingly collected.

Suicidal Caller

I hope you're not, you know, doing anything about tracing the call.

Bob Fass

Well I don't know. Suppose I was?

Suicidal Caller

I wouldn't want you to.

Bob Fass

Well, suppose I said I didn't want you to commit suicide? What do you care what I want?

Suicidal Caller

I would appreciate the thought.

Bob Fass

All right, well, I don't. I mean, I think it's a-- if you think you're going to die of a broken heart, you're not--

Suicidal Caller

The truth is that my life is in a total mess at the moment, both as far as jobs, my girlfriend, my so-called friends.

Bob Fass

How are you gonna do it?

Suicidal Caller

I've done it, I'm sorry to say.

Bob Fass

What do you mean?

Suicidal Caller

I've taken an amalgam of pills.

Bob Fass

What have you taken?

Suicidal Caller

Sleeping pills. Three different kinds of sleeping pills and some anti-depressants. And I think the totality of it will do it. At least, I hope so.

Sean Cole

I'm going to tell you right now that the caller survived. In fact, he lived for another 20 years after this. Which means he died when he was 68. I can't find any record of how he died. But I'm telling you this in part because I don't want that question to distract you from how this phone call played out.

I've really never heard anything like it. I feel like a lot of times, in stories like this, the people trying to stop a potential suicide victim tiptoe around that person gingerly, careful not to make any sudden moves. Bob didn't do that. He didn't treat the guy like a potential victim. He treated him like a person, like anybody else calling into the show. And to be a person with someone who's about to cease being a person, that just takes an awful lot of nerve.

Bob Fass

At first, I thought it was a gag.

Sean Cole

I went out to Bob's house on Staten Island to talk to him about this call, ask him what he remembers. Which is not a ton, but certain things have stuck with him. He says WBAI had been doing a fundraising marathon that night, and the calls were all coming into the pledge room. He thought maybe the caller was just trying to get on the air and said this crazy thing to make sure they'd patch him through.

Bob Fass

You ever heard the expression "a dead baby call?"

Sean Cole

No.

Bob Fass

Talk show language. In the middle of a happy time, someone calls up and says, "My baby just died." A wet blanket call.

Sean Cole

I see.

Bob Fass

But when his speech began to slur, it didn't seem like a typical call like that.

Suicidal Caller

Do you know what? It's not because I don't trust you. I'm going to hang up.

Bob Fass

Well, wait a minute, wait a minute, wait a minute. The worst thing that can happen is somebody will stop you from doing this thing, and then you'll have another chance to do it later. Talk to me for a few--

Suicidal Caller

I've dispersed my estate, so to speak.

Sean Cole

He says, "I've dispersed my estate, so to speak." Meaning, he sent what little was left in his checking account to a handful of friends.

Suicidal Caller

I'd be very embarrassed to ask for the money back, you know.

Bob Fass

Well, maybe-- maybe it was in some way, it was all of your possessions that were hanging you up. You know?

Suicidal Caller

With all due respect, I think you're trying to trick me, and I'm going to hang up. And I hope BAI can use this in some way. You know, it's dramatic and all that. You know.

Bob Fass

Well, I mean, why do you want BAI to have the use of your death or your--

Suicidal Caller

I've never had the decency to send you 15 bucks.

Bob Fass

I don't think you ought to kill yourself over it. I mean, a little guilt is OK.

Suicidal Caller

I'm not killing myself over that. But you know, I've really never done anything for the station, and the station's a good station, and it's afforded me a lot of pleasure in a mostly otherwise drought-ridden life. And now I'm going to say goodbye.

Bob Fass

Wait a minute, wait a minute. Before you say goodbye, give us like-- it takes about 20 minutes to trace a call, and you haven't been on the phone with us for three minutes yet.

Suicidal Caller

You telling me the truth?

Bob Fass

I'm telling you the truth. It takes about 20 minutes to trace a call. I know, because we tried to--

Suicidal Caller

Why does it take so long?

Bob Fass

Because the telephone company is more messed up than your life is, and they're not about to commit suicide.

Sean Cole

I guess I would have worried that like, oh no. Like, he's going to hang up. Do you know what I mean? I think that's why I would have been-- I would have been so gentle. Do you know what I mean?

Bob Fass

Well, I thought I was trying to be gentle, but if you lull someone to sleep, that's what you're fighting against. If you can get them to show a little ire, maybe they'll hang on to life.

Suicidal Caller

I think we've been talking 20 minutes.

Bob Fass

No, we haven't been talking 20--

Suicidal Caller

15, at least.

Bob Fass

What?

Suicidal Caller

I have a good time sense. 15, at least.

Bob Fass

I don't think so. I don't think it's been more than five.

Suicidal Caller

Oh no, no. It's not five.

Sean Cole

It's eight. This is eight minutes in.

Bob Fass

I think that the drugs are distorting your sense of time.

Suicidal Caller

No, they're not.

Bob Fass

That's the first thing.

Suicidal Caller

I have a very good time sense. We've been speaking 18 minutes.

Bob Fass

All right, I'll tell you what. As a test of that, I'll start and you tell me when a minute is up.

Suicidal Caller

All right.

Bob Fass

I have a timer right here, and we'll-- it's an electronic timer.

Suicidal Caller

You'll see that I'll be right within five seconds.

Bob Fass

OK, started now. All right, you tell me when a minute is up. OK, will you bet your life on your ability to do this?

Suicidal Caller

No.

Bob Fass

No. See? You're not willing to gamble. You're afraid that something is going to happen to--

Suicidal Caller

I'm a gambler.

Bob Fass

What?

Suicidal Caller

I am a gambler.

Bob Fass

Well, then gamble on this. I mean, this is the ultimate bet of all, isn't it?

Suicidal Caller

In one shape or another, that's been in my mind since I was 16 or younger.

Bob Fass

Well, I mean, I don't think that's even unique. I think everyone has had-- has been struggling against the awareness of death.

Suicidal Caller

Right there. There's the minute.

Bob Fass

No, it's 45 seconds. You're 15 seconds off. And 15 seconds out of every minute--

Suicidal Caller

I was talking, so I got carried away maybe.

Bob Fass

All right, let's see if you can do it in silence.

Suicidal Caller

No, no, no. You're stalling me. You're obviously stalling me. I appreciate it a great deal.

Bob Fass

You're right. I am trying to stall you, and trying to talk you out of it. And I think you ought to give me half a chance.

Sean Cole

This is another remarkable thing about this phone call. The caller keeps saying, "I'm on to you. I've figured you out." But there's nothing to figure out. For the entire 45 minutes, Bob is scrupulously honest about what he's doing. This is one of the few times in life where it would be more than forgivable to mislead someone, to just keep stringing them along to keep them on the phone. And Bob never does that. Because he never did that on the air. As always, he's just a naked heart speaking into the microphone, which, in this situation, that's the ultimate bet.

Bob Fass

I mean, you called me. You called us here because you wanted to say something to us, or to people listening, or do something for us.

Suicidal Caller

Yeah, get your PR department on this. You can use a little publicity and some money.

Bob Fass

I mean, I think that's insulting that we would use someone's death. Give us a chance to find out why, and tell us, convince us that it's a right and proper action.

Suicidal Caller

All right. Let me ask you three questions. Please answer care--

Bob Fass

I'll answer very carefully.

Suicidal Caller

What?

Bob Fass

I'll answer very carefully.

Suicidal Caller

I don't care about carefully, but honestly.

Bob Fass

You started to say "carefully." Didn't you start to say "carefully?"

Suicidal Caller

Yeah, yeah.

Bob Fass

Well, I mean that stuff is important. I will answer carefully, and I will answer honestly.

Suicidal Caller

Are we on the air?

Bob Fass

Yes, we are.

Suicidal Caller

I'd rather be off. One, OK?

Bob Fass

You'd rather be off?

Suicidal Caller

Yeah.

Bob Fass

OK.

Suicidal Caller

Off the air.... And two, I would like your promise that-- your sterling promise that you're not going to have this call traced. Do I have that?

[SIGHING]

It's a tough one, I know.

Bob Fass

It is a tough one. I mean, it's really like-- because you see what you've laid on me?

Suicidal Caller

I know. But I wasn't always this way.

Bob Fass

Yeah, but don't you see? I don't think you could get that promise out of any human being.

Sean Cole

It was not easy to trace a call in 1971. And in this case, it took a lot longer than 20 minutes. The process is way too complicated to explain here, but it was a mechanical process that involved multiple people at the phone company's central office. And it may have already been under way by the time the caller asked for it not to be. In any case, it wasn't like Bob was doing it himself. And again, he could have said to the guy, "Sure, I won't trace it," just to appease him. But Bob says that didn't seem right.

Bob Fass

This is a guy who might be dead. And if the last thing that someone told him was a lie, that's heavy. I didn't want to do that.

I'd like to continue talking to you for a while.

Suicidal Caller

All right, got but only with that promise that you're not going to have the call traced.

Bob Fass

I can't promise that, but I mean, you can force me to, if you'll say that's the only way you'll talk to me. But it's not a promise that I want to make.

Suicidal Caller

I'll stop talking to you then, because I don't want to have a kind of messy night with a lot of beefy Irish policemen sitting at the foot of my bed.

Man

What have you got against the Irish?

Suicidal Caller

Nothing. I rather like the Irish.

Bob Fass

Yeah, we got a priest down here who'll talk to you too. He'll be up in a minute, sonny.

Sean Cole

Around about the 20 minute mark, something weird happens. The conversation floats down to earth and becomes totally normal. Imagine for a second that this is where you came in, that you've heard nothing else up till now.

Suicidal Caller

I despise Orson Welles, but he's not himself in this movie.

Bob Fass

Why do you despise Orson Welles? Everybody digs it.

Suicidal Caller

I find him so hammy.

Bob Fass

Because of those airline commercials?

Suicidal Caller

I don't know the airline commercial.

Man

He was great in Citizen Kane.

Sean Cole

Yeah, I mean, no, I don't think so. I mean, I think that he may have been hammy throughout his career, but the hamminess has become him.

Suicidal Caller

That's like an old Betty Field movie. Did you ever see that? It was called Tales of Manhattan.

Sean Cole

Turns out the caller's a real movie buff. He works in media, writes satire, some humor. He's a freelancer. He and Bob dreamily run through one of the plotlines of an old Betty Field movie called Flesh and Fantasy.

This is what most of the calls on Radio Unnameable were like. Bob didn't screen them, and there was rarely a point to them. It sounded more like family catching up with each other. And by the way, this wasn't the first time that someone called up the show who was suicidal. Bob says a woman called once, threatening to kill herself, and he managed to talk her down. He says she's still around, doing OK.

Bob Fass

If someone is so lacking in friends and other human contacts that they need the voice that comes out of the radio to be their friend, they're really-- they're in trouble, you know? I mean, I can remember in my life when there were times that the only thing I could trust to the extent that I could trust it was the voice coming out of Long John or Jean Shepherd.

Sean Cole

These are radio personalities in your day?

Bob Fass

That's right. They had carved a place out of the universe that was reasonably sane for them.

Sean Cole

And they were overnight announcers too, Long John Nebel and Jean Shepherd. The difference is, they weren't exactly the kind of guys you'd call up when you'd already swallowed three kinds of pharmaceuticals. If this caller was looking for empathy, empathy is what Bob specialized in.

25 minutes in, Bob seems to have gotten to the guy, in a good way. His guard is down. He's relaxed. He's also on a supreme amount of sedatives, so there's that. They're talking about the smallest little thing. The guy says he's drinking seltzer. Bob asks if it's one of those old fashioned Marx Brothers type bottles that you squirt. The caller says no.

Suicidal Caller

This is bad, but you can't get that on the East Side. There's a clue.

Sean Cole

"There's a clue," he says.

Bob Fass

That's weird, that you can't get that on the East Side.

Suicidal Caller

Yeah, at least as far as I know, you can't. At least not on the Upper East Side.

Bob Fass

I think you can. I think if you live in a neighborhood where the seltzer man isn't afraid of junkies jumping him in the hallway, you can get seltzer delivered. Doesn't that make you want to live?

Suicidal Caller

Almost. It's not that I don't want to live. It's that I do want to die.

Bob Fass

Why do you want to die?

Suicidal Caller

Oh.

Bob Fass

I mean, can you talk-- I mean, if dying is so hot, why don't you try to talk me into it?

Suicidal Caller

No, it has to be a very individual decision.

Bob Fass

All I ask you to do is to explain in a manner that I could understand why you were going to do yourself in, so that I would say, oh yeah, that's a logical decision.

Suicidal Caller

Well, I'll try.

Sean Cole

He says, "Well, I'll try." But then he doesn't. What gets me the most about this whole call is the tone in Bob's voice during it. At the very same time he's being empathetic, he's also saying, "No, don't." It's one of the trickiest balancing acts you can try when relating to another person, something you usually only do when you've reached a bedrock level of intimacy with someone. And here he's doing it with a complete stranger. But Bob says there's a way in which he felt connected to the guy.

Bob Fass

Without going into it too deeply, I had been severely depressed at one important point myself. And I recognized that it's possible to come back, you know? So--

Sean Cole

You could identify with that feeling.

Bob Fass

I could. Now you've gotten-- you gotten me a little agitated here.

Sean Cole

Oh, I'm sorry. I'm sorry.

Bob Fass

Well, it's nice to know you're alive.

Sean Cole

At about minute 38, the caller starts to slip into that liminal space between waking and sleeping. His speech is so slurry it's almost incomprehensible. Like tape that's been slowed way down. He keeps talking, but you can tell he's starting to dream at the same time.

Bob Fass

Voices?

Suicidal Caller

The kids.

Bob Fass

The kids? What kids?

Suicidal Caller

The kids--

Sean Cole

Then he stops making sense.

Bob Fass

Well, what did "the kids" mean? You said something about kids.

Suicidal Caller

Yeah, in Milano. In Milano.

Bob Fass

In what?

Suicidal Caller

Near-- near-- near Milano, a city in Italy.

Bob Fass

Oh, Milan.

Suicidal Caller

Yeah.

Bob Fass

I don't understand.

Suicidal Caller

I think I'm going.

Bob Fass

Stand up. Stand up, stand up.

Suicidal Caller

Trying to stand up.

Bob Fass

Please try and stand up. Do it. You can do it. Just get up on your feet. Pitch yourself up on your feet.

Suicidal Caller

My feet?

Bob Fass

Yeah.

Sean Cole

New York Times, November 7, 1971.

Bob Fass

At about 2:45 yesterday morning, a man telephoned Radio Unnameable with WBAI talk and music show, and told its moderator, Bob Fass and the station's listeners, "I'm going to commit suicide."

Get up, get up.

Suicidal Caller

[MUMBLING]

Bob Fass

The New York Telephone Company assigned more than a dozen persons to trace the call.

Stand up, stand up, stand up.

And they determined that the call originated from the East Side.

Stand up.

The police of the 104th Street Station were then notified.

Get up. That's it. Get up.

Listeners called the station. "The man's voice sounded familiar," one said. "What are the police doing?" asked another.

Hello?

Mr. Fass asked his name.

What did you say your name was?

Suicidal Caller

Stanley.

Bob Fass

Stanley what?

Suicidal Caller

Kaufman.

Bob Fass

Stanley Kaufman?

Of course it wasn't Stanley Kaufman. Stanley Kaufman was the drama critic of the Times.

I think I know that name. Have I ever seen it published anywhere? Stanley? Stanley?

At 6:30 AM, the police, acting on information from the telephone company, found a man lying unconscious on his bedroom floor.

Stanley?

At 110 East 87th Street. His telephone was off the hook, and three empty pill bottles were at his side.

Hey, Stanley! Stanley!

The police said the man was identified by his landlady and his estranged wife as Michael Valenti, 47 years old. The man was taken to Metropolitan Hospital, where he was being kept under observation. Still unconscious yesterday afternoon.

Stanley? Stanley!

[SNORING]

Sean Cole

Bob finally took the call off the air and started playing this song, Hello, I Love You by The Doors. But he didn't hang up the call. He played music down the phone line instead for another three hours, in case it would help the phone company. Thought they might be listening in while tracing.

Bob says he did hear from Michael Valenti again, years later. Valenti called him, not on the air, just a regular phone call, to say thank you, and to tell him, "I got a job." "That's wonderful," Bob said. And this is according to Bob, Valenti says, "I want to do something for you. I'm working for Hustler Magazine. I give advice to the lovelorn. And if you want, I can get you a column where you give people advice to help them with their sexual problems." As always, Bob listened and responded candidly. He said no.

Just a note that there are a lot of non-radio resources available to people who are in trouble, thinking of suicide. For example, there's the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. The number is 1-800-273-8255. Thanks to Jessica Wolfson and Paul Lovelace, who made the excellent documentary Radio Unnameable. It's streaming on Amazon and iTunes.

Coming up, the woman in charge of getting people to the streets they walk down every day, and yet don't know their names. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio, when our program continues.

Act Two: A Road By Any Other Name

Sean Cole

It's This American Life. I'm Sean Cole. Today's show, Who You Gonna Call? Stories of people finding the specifically perfect person to ring up in their times of need. And now we're at Act 2 of our show. Act 2, A Road By Any Other Name.

We heard about this woman in New York, who an entire community calls on the phone every day to help them get around town. She's essentially the keeper of a secret map of the city. Aaron Reiss finally secured an audience with her after meeting some of the people she helps.

Aaron Reiss

A while back, I moved to New York City from China, where I had just spent two years. I wanted to find a way to keep up my Chinese, so I moved into a cramped apartment on Rutgers Street with three elderly immigrants, a married couple and a single man, all in their 70s. And none of them spoke English. I would help them translate their mail. They would feed me home cooked food. We had a good thing.

But sometimes I wouldn't understand what they were saying. The woman, for example, tended to go on at length about our neighbors and the noise from upstairs. And even though I'd pick up only a quarter of what she was saying, I would nod along, commiserating, like, totally, I know.

One night, we were in the kitchen talking about what we had done that day. And I was having a really hard time understanding where they had gone. They kept saying this was a place on La Zha Gai, which means dirty or garbage street. But I had never heard of that street.

After a confusing four or five minutes, I realized that they were actually referring to the street we lived on, right where we were standing. It was just a nickname that a lot of people used for Rutgers Street. I started looking into it, and I learned the streets in Chinatown all have these Chinese names. And not just one. Streets can have four or five different names, each used by a different population in Chinatown-- longtime Toisanese and residents, recent immigrants from Fujian, Cantonese. And there are actually these different Chinese maps of the city with the same streets but different names. I started collecting them. I buy them from this guy, DiCheng, who sells them on the corner.

And there are a few people, though not many, who have to know all the names on all of the maps. Like this woman.

Mona

Hello, Lucky?

Aaron Reiss

Mona is a human street name almanac, because it is her job to know. She's a dispatcher at a car service in Chinatown called Good Luck. She's in her mid-40s, lots of jewelry, no makeup, glasses. And she's always wearing this expression like, "Do I really need to be explaining this to you right now?"

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

Right now, she's taking a call from a Cantonese customer who's looking for a car.

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

She's asking, "Where are you?"

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

The customer just asked to get picked up on La Zha Gai, Garbage Street. Unlike me, Mona doesn't miss a beat. She knows exactly what the caller is talking about. She tells the driver to go to Rutgers, in English. Then she turns to us and explains one reason why people in Chinatown started using these nicknames in the first place.

Mona

Rutger Street, they cannot pronounce it. So that's why they gave Rutgers Street a nickname. La Zha Gai. La Zha is easy for them.

Aaron Reiss

To understand how this plays out, let's start with just one street, Orchard Street. First, it's got its Cantonese name. Uo Cha Gai. Sounds like "orchard," right? Then its Mandarin pronunciation. Ke Cha Jie. Then there are its translated names, which literally mean "orchard" in Mandarin and Cantonese. Guoyuan Jie and Gwoyoon Gai.

Then there's its nickname. Orchard used to be a main street for Jews. So depending on the level of your grandpa style racism, you might call it Jewish Street. Or, as one older guy told me, it's kind of like Cheapskate Street. There are a few versions. I'm Jewish, so don't get me started.

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

At any given time, there are between three and five dispatchers at Good Luck's tiny Chinatown office, sitting in a row, each of them manning a few phones at once. When Mona hears Dead Person Street, she sends a car to Mulberry, which she knows is named after the funeral homes and florists on the block. When she hears Hatseller Street, she sends a car to Division Street, because, historically, well, hats.

There are some puzzlers, like the Kosciuszko Bridge, named after Thaddeus Kosciuszko. Everyone calls it the Yat Boon Jai Kiu, which literally means "the Japanese Guy Bridge." I asked some older ladies in Chinatown why.

Woman

Because it has so many consonants and vowels, that it looks like a Japanese name.

Aaron Reiss

He's Polish.

Woman

Ah, Polish?

Mona

Yeah, hello. Lucky.

Aaron Reiss

One day, I was visiting Mona at Good Luck, and she was on the phone with a customer, navigating between a couple of different names for the same section of East Broadway. One is like Fujianese shorthand. Hi Dong Lo, and the other is the Mandarin name, Dong Bai Lao Hui.

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

Yeah, so you're going to East Broadway, am I right?

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

Number 88, Hi Dong Lo, am I right?

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

And where in Flushing is he going?

Mona

Bye-bye.

Aaron Reiss

Then another Mandarin-speaking customer calls.

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

So right now where are you?

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

She's using two different names for Canal Street, Canal Jie and Canal Lu.

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

The customer is not understanding, and is talking over Mona. Mona's like, "Slow down, listen to me," trying calmly to get on the same page. But the first time I visited Good Luck, Mona was in the front office with one phone pressed against each ear. In one receiver, she was screaming over and over again at the driver in Mandarin. "She's on Grand Street, Grand Street!" And then switching to the other receiver to try and sweet talk the English-speaking customer.

Just as a side note, English-speaking customers expect more coddling. Here's how Mona sounds when she talks to Chinese speakers.

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

But listen to how she is with English-speaking customers.

Mona

Hi, good morning. Hi, how can I help you?

Aaron Reiss

Anyway, that day with the two phones at her ears, Mona told me she was getting fed up with being the interpreter between two angry people.

Mona

You keep telling the passenger that the driver is in front of 570 Grand Street. She don't get it. And I tell the driver you parked at the wrong location. You keep telling the passenger that the driver is in front of 570 Grand Street. She don't get it. And I tell the driver you parked on the wrong location. They both don't listen. I hate it.

Aaron Reiss

Why do you hate it?

Mona

I'm the middle. She have her own way. He has her own way. So I hate it in the middle.

Aaron Reiss

But she doesn't quit.

Mona

I wish I could. I wish, because once you're in this thing for a long time, you're addicted to it. It's exciting. Sometimes you yell at the people, yell at the driver. It's like the time goes fast.

Aaron Reiss

A lot of people depend on Mona, people who can't just hail a cab or call an Uber and describe to a non-Chinese driver where they want to go. And even if they could, there's the name trouble. Your average New York cabbie probably can't chart a course for 24 Dead Person Street, or 54 Monkey Street. For those people, there are just a few places to turn for help, a handful of car companies and dispatchers like Mona.

And customers are grateful. On Chinese New Year, old ladies head over to Good Luck's office on Ludlow Street. They hand over red envelopes with a few dollars inside, her name written at the top. "For Mona."

Act Three: Ode to Joy

Sean Cole

Act 3, Ode To Joy. There's this thing President Trump used to say before he got elected. It was part of his regular stump speech, kind of a rallying cry.

Donald Trump

We're gonna start winning again. We're gonna win so much, you may even get tired of winning! And you'll say, "Please, please, it's too much winning. We can't take it anymore. Mr. President, it's too much!"

Sean Cole

And without going into the merits of whether the president is getting tired of too much winning, or whether it is in fact even possible to get tired of too much winning, our program today deals in some ways with advice. And I do think it's possible to get tired of too much advice, for someone to offer so much good advice that's so perfectly suited to you that at some point you decide it just pains you to hear it.

The regular host of our show, Ira Glass, heard of that happening to a friend of his. Here's Ira.

Ira Glass

The friend is my friend Lucy. And the person who gave her such good advice was not me. Which-- OK, I'm not hurt by that. I personally think the advice that Lucy and I give each other is excellent. Lucy can think what she wants. When it comes to advice, I know that the person who's advice has been a consistent north star in Lucy's life for like 15 years now is a professional advice giver, a psychologist on a call-in radio show who gives advice over the air-- Dr. Joy Browne.

Lucy says she likes Dr. Joy Browne because, unlike some other radio psychologists that she's listened to in the past, Dr. Joy Browne doesn't smack her callers over the head with a frying pan and tell them what they're doing is wrong. Joy Browne is kind but deeply pragmatic. There's a whole raft of principles and mottos that come up over and over, all of which Lucy has internalized. Like, "Stupid and cheerful."

Lucy

If somebody is trying to engage you in some sort of passive aggressive issue, you just try to be as stupid and cheerful as possible. So like, if somebody comes into your kitchen and is like, "Oh, you're painting it this color?" You just go like, "Yup. Isn't it great?"

Ira Glass

Oh.

Lucy

You know? Stupid and cheerful. It really works.

Joy Browne

My dear, this is one of those times that you're going to have to be stupid and cheerful.

Ira Glass

This, of course, is the doctor herself, talking to a 23-year-old woman named Michelle, who lives with her mom, who explains to Dr. Joy Browne that she's ready to move out.

Michelle

Yes, the difficulty is, is that she suffers from mental illness, and she is severely depressed, and she gets verbally abusive, and she yells, and I need to leave.

Joy Browne

OK, how old is mom?

Ira Glass

Dr. Joy Browne runs through a quick series of questions and ascertains that the mom is 55, not working, single, under therapist care, on meds. Then she pivots to her advice-- stupid and cheerful.

Joy Browne

Equal emphasis on stupid and cheerful. If you go in to your mom, and say, "Mom, I know this is going to really upset you, but it's time for me to leave," if you deal with the subtext, "You're abandoning me. I can't believe you're doing this," you're lost, and so is she. It's not like it benefits either of you. So we're not going to do that. Just be stupid and cheerful.

Michelle

OK.

Joy Browne

What you need to say is, "Mom, you know what? I found this great apartment. Will you come and help me find some furniture?" And what you're going to have to do is decide that you're going to win the Meryl Streep award for Brooklyn, all right? And you're going to say, "Mom, I'm so excited." And you're going to have to be stupid about the fact that this may be traumatic for her. But it's not your responsibility to take care of your mom at this stage in your life.

Lucy

You can show up on the phone with whatever kind of messy, emotional or non-emotional, trivial or not trivial problem. And you hand her the Rubik's cube of that, and she would ask a few questions, and hand it back to all put together with all the colors on the right side.

Joy Browne

Mom's gotta learn to take care of herself.

Michelle

OK.

Joy Browne

All righty? Stupid, honey. Stupid and cheerful, stupid and cheerful, stupid and cheerful. All right?

Michelle

All right.

Ira Glass

Lucy likes how encouraging Dr. Joy Browne always is, and kind of good humored. And she's listened to her for thousands of hours, first on the radio, then on podcast. The show is three hours every day. Now Dr. Joy Browne has such a hold over Lucy's thinking and over her heart that Lucy will say things like--

Lucy

Well, you know, we didn't always agree on everything, but mostly.

Ira Glass

The phrase "we didn't agree about everything" implies that she was in on this relationship too.

Lucy

Well, sort of. Although we didn't agree on everything. You know, she had some beliefs that I didn't believe in.

Ira Glass

No, again, there's no "we."

Lucy

I guess you're right.

Ira Glass

The look in your face, I said that and your feelings looked really hurt, and I suddenly felt sort of bad.

Lucy

No, don't feel bad. I mean, I guess my relationship with Dr. Joy Browne is at the intersection of incredibly lighthearted and really, really deep-seated and emotional, for me. Like a radio call-in show psychologist, it's a low stakes, right? Except, it's not really. Because people call in with real problems. And so with her, the relationship sits right in the middle of being kind of like a joke and being like a super serious part of my psyche. You know?

Ira Glass

Yeah.

Lucy is so in tune with what Dr. Joy Browne would say in any situation that sometimes when friends and family turn to her for advice, she just doles out whatever she thinks Dr. Joy Browne would say. Like, when her aunt was in a relationship where she was not getting what she wanted, very unhappy, feeling awful.

Lucy

And I said to her, think about what the relationship is like now. Think if you knew you were never going to get any more than this, and you were never going to get any less than this out of the situation. Would you stay or go? And if you would go, how long would you wait before you go? That's straight up Dr. Joy Browne.

Ira Glass

Mhm.

Lucy

And my aunt thought that that was really stellar advice, and it really helped her. And then I had to admit to her that I had gotten it from someone else. But she was still into it.

Ira Glass

Lucy's called Dr. Joy Browne for advice a half dozen times over the years. She called her for advice the first time when she was just 21, after moving in with her boyfriend. She had never lived with a boyfriend before, and it was going badly. And she did have friends she could turn to for advice, and she could call her mom, who she's really close to. But she didn't want to admit to anybody that she knew that things were going so poorly. Dr. Joy Browne was the perfect anonymous friend.

This phone call was so long ago that we weren't able to find recordings of it. Lucy says she was sitting on the floor in the hallway of the little apartment in North Carolina when she phoned.

Lucy

You're hearing the radio show in the phone, because you have talked to the screener. You've told them your question. And then you have to wait until she says your name.

Ira Glass

Yeah, what's that like?

Lucy

It's incredibly nerve-wracking and, you know, palms sweating, and thinking about hanging up, and just wondering when it's going to happen. She could say your name at any time. And then she does. She says "Lucy, what's your question?" And I describe my situation, and I think that I cried a little bit. That's my memory.

Ira Glass

What was her advice?

Lucy

Her advice was to leave the relationship right then.

Ira Glass

How many minutes did you talk to her before she said that? Like, was it 10, 5?

Lucy

No, maybe like 2 and 1/2.

Ira Glass

2 and 1/2 minutes?

Lucy

Yeah.

Ira Glass

Wow, that's a really sobering thing, that you could talk to a stranger for 2 and 1/2 minutes, and they're just like, "Yeah, got it. OK, leave him."

Lucy

Yeah, she said leave. And she said, get your own apartment, and start your own life there, and just get out of the situation.

Ira Glass

Did you think it was good advice?

Lucy

It was not what I wanted to hear. I wanted to be told how to fix it, you know? That advice to leave seemed completely impossible.

Ira Glass

How long did it take for you to leave?

Lucy

It took about a year.

Ira Glass

In retrospect, do you think you should have taken the advice when she gave it to you?

Lucy

Yes

Ira Glass

Why call in to an advice show if you're not going to take the advice?

Lucy

I think, in a way, my mind went blank, and I was just shaken by her response. I just thought, this person who I've come to know and trust so much? I don't know. I was pretty shocked that she told me I should leave.

Ira Glass

Lucy called once for advice about dealing with her parents, and once for advice about a situation with her sister. Both times she took the advice, and says it went great. One of her professors was dying. She wanted to write him a letter saying some nice things, but wasn't sure that somebody would want to get a letter saying "I hear you're dying, and so I wrote you this letter." Dr. Joy Browne told her to send the letter. Of course send it. It's kindness. Which she did.

And something else happened on that call that Lucy loved.

Lucy

She called me "cookie" during that call, I remember. Which is something that she called a lot of people from time to time. So it was a thrill to me.

Ira Glass

But did she only call them cookie if she liked them?

Lucy

I think it was an affectionate term.

Ira Glass

It sounds pretty affectionate.

Lucy

Yeah, I mean, cookies are great.

Ira Glass

Noted.

This went on for years. Lucy listened to Dr. Joy Browne for hours every day, and occasionally phoning her up for advice. And then her whole situation with Dr. Joy Browne took a turn. This happened in just the last few years, during the time that Lucy and I had been friends. Lucy was having some troubles, and was really pretty miserable. And she could have called Dr. Joy Browne for advice, but she never did.

Lucy

No, actually, for the last few years, I had not been listening to her. I stopped listening to her, in large part because I got into several relationship situations in a row that I knew that she would totally not approve of.

Ira Glass

One of them is somebody who is possessive and not so nice to her. One was somebody married, separated but married.

Lucy

And I think it became too embarrassing for me to listen to her, the way that I used to.

Ira Glass

You mean embarrassing like you feel like you couldn't be in her presence because you knew what she would think of what you were doing?

Lucy

Yeah.

Ira Glass

You felt like you knew her that well?

Lucy

Yeah, I felt like if I had called her with a problem about one of these relationships, we wouldn't have even gotten to my problem I was having. She would have, right off the bat, said well, the problem here is that you're not following the One Year Rule. She had this thing called the One Year Rule.

Joy Browne

Yeah, well, I keep telling people you need to go through a year by yourself after the breakup of an important relationship, whether it's divorce or death.

Ira Glass

This is Dr. Joy Browne explaining the One Year Rule to a caller.

Joy Browne

Because you'll make different decisions based on need than you will on want. And when you're feeling really lonely and really sad, you'll succumb to things that, if you're feeling better about yourself, you wouldn't do.

Ira Glass

And this is a caller named Angela who phoned to thank Dr. Browne for the One Year Rule.

Angela

You know, Dr. Joy, in the beginning, I was thinking Dr. Joy is crazy. One year? That's a long time.

Joy Browne

Yeah.

Angela

But no, it is the greatest time I've been having all these days.

Joy Browne

Well, that's great. And you're probably a much happier person than you were a year ago, which means that you're going to be much more date-able, and you'll find somebody who is more wonderful than you would have a year ago. So that's great.

Angela

Yes, I am super super duper happy! Thank you very much, and God bless you.

Ira Glass

So Lucy knew the score. She hadn't obeyed the One Year Rule. The people she was with hadn't either. And she saw the basic wisdom of the doctor's One Year Rule.

Lucy

And I knew that she would have said like "No, no, no. This is not going to work. You've got to get out of it." I think it became a lot less fun for me to listen to her because I knew that I was in a mess, you know? And I knew that if I had really taken her advice, I wouldn't be in that mess.

Ira Glass

Lucy was like a sinner who doesn't like stepping foot in church, because it reminds 'em just how far they'd fallen. So she stayed away. And then, finally, not long ago, Lucy got out of that last relationship. She was single again. And it only took a day or two after that.

Lucy

And I was in a taxi, and I suddenly thought, "I'm going to look up Dr. Joy Browne's podcast, and I'm going to start listening again.

Ira Glass

Right, because finally you could. Because you felt like you wouldn't feel this guilt.

Lucy

Yeah, I had a clean slate.

Ira Glass

Mhm.

Lucy

So I looked her up, and I was totally shocked and horrified to find that she had just died two days before, very suddenly. And I was really sad, and really panicked. Like, no, no, no, wait, wait, wait. I need to-- like, what? No, no, no. I need to listen to your show. You can't die.

I just was going to start listening again, and I just missed her. Like, I just missed her by two days. She was doing her show that week. She was totally well, and as far as anyone knew. And I was really sad.

Ira Glass

How long had you not listened to her?

Lucy

Probably-- maybe five years.

Ira Glass

Do you feel like you let her down?

Lucy

Yeah, I felt like I'd jumped ship, and taken her for granted, and thought she would be there when I resurfaced from whatever kind of messy mess I had gotten myself into. You know that thing that people say, "When I just like make enough money, then I'll get my life together, when I just lose enough weight, then I'll get my life together." And I think in the period where I stopped listening to her, I was thinking like, "Once I sort all this out, I'll get back to listening to Dr. Joy and I'll resurface as the person I was before, once I clean up this mess." But I never did. And then, when I resurfaced, she was gone.

Ira Glass

It made her totally re-evaluate her relationship with Dr. Joy Browne. All those years she thought, the two of them so in agreement. She felt so close to her. It made her realize, oh, maybe she was just kidding herself.

Lucy

I guess it does use to listen thinking people would call in, and they'd give their situation, and I'd just think, "Oh boy, here's the problem with what you're saying. I know what she's going to say." And then she would say it, and I was sitting back like, "Dr. Joy and I, we know the rules, and that's not going to work."

Ira Glass

Yeah. And it's like you and her against the losers. But then you were going like, "Oh, wait a second. No, I'm one of the losers."

Lucy

Well, I mean, losers, she had a warm heart.

Ira Glass

She wouldn't use that word. No, but you know what I'm saying.

Lucy

They were like the people who were astray. And you know, I had a lot of big ideas about how I had it together. And I was doing it wrong too. And even though I knew better, even though I used to sit there, imagining myself near Dr. Joy Browne, I know what she would say, but I would feel better if she were here to say it.

Ira Glass

Yeah. There's a thing that people say to each other in movies that I've never, ever in my life had an impulse to say to somebody, but I do now. And that is, "Well, you carry her inside you."

Lucy

Um, well, what does the other person in the movie say, then?

Ira Glass

Usually, they're really moved.

Lucy

Oh, well.

Ira Glass

In the movies! Hold on for a second. This is the kind of music that we play in the movie. Hold on. Stay right there.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

It's going to be this kind of music. I'm going to say it to you again. Lucy, even though she's gone, you don't have to feel bad, because you carry her inside you.

Lucy

And then I would just say, "I guess you're right."

Ira Glass

There you go.

[CHUCKLING]

That was excellent line-reading.

Sean Cole

Ira Glass. That kid's got talent, right?

Our program was produced today by Stephanie Foo. Our staff includes Elna Baker, Elise Bergerson, Susan Burton, Dana Chivvis, Whitney Dangerfield, Neil Drumming, Kimberly Henderson, David Kestenbaum, Chana Joffe-Walt, Seth Lind, Jonathan Menjivar, BA Parker, Christopher Swetala, Matt Tierney, Julie Whitaker, and Diane Wu. Our senior producer is Brian Reed.

Special thanks to Eric Mennel, Louisa Gao, Bing Yen, Hamilton Madison House City Hall Senior Center, Judy Lei, Ya Yun Teng, and the Museum of Chinese in America, Joo Wai Foo, Chuck Leung, and Michael Harrison. Research help from Michelle Harris and Lu Fong.

Our website, thisamericanlife.org. This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange. Extra special thanks this week to my boss, Ira Glass. I assured Ira before he left. I was like, "Absolutely, go away this week. It's fine. We'll air a re-run."

Ira Glass

With all due respect, I think you're trying to trick me.

Sean Cole

I'm Sean Cole. Call your mom, and join us next week for more stories of This American Life.