659: Before the Next One

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue: Prologue

Ira Glass

It's a school trying to do the right thing, a school trying something new, trying to keep its students safe. So they bought handguns, seven of them, Glock 9mm, to use if a shooter comes into their building. And a week and a half before school started, after a bunch of training, they were running their first drill in the school building with their guns, fresh out of the boxes.

Man

Here, look at them, make sure they're all loading. Look at them. They all should be.

Ira Glass

The building's mostly empty, no kids around. It's a district in rural Ohio that let us record on the condition that we not say their name on the air. It's eight people on this team. Only two teachers volunteered for it.

The rest are a guidance counselor, two custodians, and the three administrators who run the school. One of them is the only woman on the team. Producer Lisa Pollak watched them doing this. Lisa, so explain how this works exactly.

Lisa Pollak

OK, so the seven guns are locked in these small safes that have been installed in locations all over the school. I saw them run a bunch of drills. And in all of them, the goal was to run to the nearest safe, get the gun out of the safe, and then get to where the shooter is as soon as possible. And they time each drill.

Ira Glass

OK. We're going to play a tape of this. I just want to warn listeners there are loud gunshots from blanks that they fired during these drills.

Lisa Pollak

So the first little glitch they came to was that some of the team members actually had trouble getting into the safes. You have to put your finger on the sensor.

Ira Glass

It's like a fingerprint thing?

Lisa Pollak

Right. And it's a little tricky.

[BEEPING]

Man

It's not working.

[BEEPING]

[MAN SPEAKING ON RADIO]

Lisa Pollak

There's a sheriff's deputy. He's playing the shooter.

[GUNSHOT]

I'm following a guy named John. He's the principal for grade six through 12. He's running from his office, darts by the cafeteria. He's got a gun. He's wearing a bulletproof vest. He's holding a walkie talkie, very focused, very aware the clock is ticking. He's told me that every few seconds in of one of these shootings, another kid can be killed.

John

Nothing this way, nothing this way.

[GUNSHOT]

Elementary wing, it's in the elementary wing.

Man

Elementary wing, the body from [INAUDIBLE].

Woman

The shooter's in the elementary wing.

Ira Glass

Elementary wing-- the building also has middle school and high school.

Lisa Pollak

Right. So the principal's running down the hallway, and he's just about to get to the area where the elementary kids are. But there's a door there, and it's locked. This happens automatically when the school goes into lockdown. So he and the two guys with him are stuck. He fumbles for his keys, and he's trying to find the right one.

John

Yeah. [INAUDIBLE].

Lisa Pollak

He's trying to unlock the door.

John

Here we go.

[GUNSHOT]

Jesus.

Man

Behind you.

John

All right. Here we go. There we go.

Lisa Pollak

Door opens. They're on the elementary school side. And they find the shooter right there. So that's the goal of the exercise. They got there. And they don't pretend to shoot him or anything. They're just timing the response. And it wasn't great.

John

That was an eternity compared to the first time.

Man

Yeah. Oh, yeah, it was because you got to get through the doors.

Woman

All clear. Thank you for your cooperation.

Ira Glass

Lisa, it's so controversial to put guns into a school. Like, why did they choose to do it here? Like, why did that seem like the best option to them?

Lisa Pollak

Well, I talked to John, the principal, about this.

Ira Glass

Yeah.

Lisa Pollak

For a long time, he agreed with people who think guns in schools is a bad idea. And even now, he doesn't think it's something that's right for every school. He says he's not a gun guy, didn't grow up with guns, had never used one. Then he came to this school. And this school is pretty remote, in an area that doesn't even have its own police force. So if a shooter got in the building, they could be waiting a long time for help.

John

I don't know that I was necessarily sold that this was the right thing to do, but what are we going to do? We're 15 minutes away from an ambulance being here. We're 15 minutes away from a sheriff department being here. We're 15 minutes away-- you worry. You worry because you realize that you're on your own.

And so I wanted to learn. And so I went out and started learning how to shoot a gun and how to handle a gun, and-- which is different. The first time you shoot a gun, that's pretty scary. It was scary to me.

Lisa Pollak

After that, he went through a lot of training, including one class where he was really forced to think through what it would mean, in a very literal way, to have to shoot someone in school. In one exercise, the instructor said--

John

You need to walk up to the target till as close as you can. And he says, and in your mind, you have to envision this as a shooter in your cafeteria, and there's students all around. How close do you have to get before you're confident you're going to hit that target? You've got to shoot that target, and you can't miss.

I can't miss. Because if I miss, there's a possibility of somebody else getting hurt. All right? And I can't let that happen. I can't let it be me who hurts a student in my school.

Lisa Pollak

Though, of course, he might have to shoot one of his students. In a lot of these shootings, that's who the shooter is.

John

If you had told me years ago that this is what I'd be advocating or thinking, I wouldn't have believed you. But these things don't stop happening. They just continue to happen.

Ira Glass

These shootings do just continue to happen. Today on our program, we have all kinds of people trying to figure out what to do to prepare, like the staff at this school. In general, it seems to plan for disaster, school administrators and others look at previous shootings. They look to the past to anticipate the future, knowing full well the whole time there's a limit to what any planning can accomplish. If a shooter gets into a school, the sad fact is you cannot stop every tragic possibility. You can't stop everything.

Act one of our show today, we have people who are trying to learn from the past. They're trying to put in measures. They're trying to be as thoughtful and thorough as they possibly can, and it's still not enough. Act two, we have people who have invented something that actually seems to work and help.

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Stay with us.

Act One: Ready As You’ll Never Be

Ira Glass

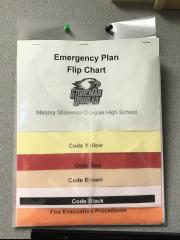

Act one, "Ready As You'll Never Be." For any school that's trying to figure out the best ways to prepare for a gunman, there's an example out there that might be really helpful, and that's Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Just a month before the shooting that killed 17 people in that school, the teachers trained their students on new procedures they should follow in that exact situation. This came after a total overhaul of the school's emergency response planning. And the day of the shooting in a television interview, one of the teachers reflected on the effectiveness of that training.

Teacher

But I don't think we could have been more prepared than we were today. And I mean, they knew what to do and we knew what to do. And even still, even with that, we still have 17 casualties, 17 people that aren't going to return to their families. [CRYING] And to me, that's totally unacceptable.

Ira Glass

Did the training they received save lives that day or didn't it? It's actually an open question. One of our producers, Robyn Semien, went to Parkland to talk to the teachers about what was actually in the training and how well it did or did not prepare them for what they went through.

Robyn Semien

The training they did at Stoneman Douglas High School was an attempt to be as prepared as possible for a wide range of emergencies-- bomb threats, hurricane warnings, a bank robber nearby, an active shooter. Douglas is a school with 11 buildings and over 3,000 students, so upgrading all their emergency procedures took months to plan and coordinate with faculty and district officers, police and fire departments.

Melissa Falkowski teaches journalism at the high school. She's the teacher in that news clip you just heard. And the training was on her mind that night because she was on the committee that set it up. She's an enthusiastic teacher, a planner. She believes in a good hard think and being proactive.

Once she and the other teachers had been trained, they ran their students through all the new drills. The whole school did this over two days in January. Teachers were told--

Melissa Falkowski

We want you to go back to every single class. We know it's going to be annoying. We know the kids are going to get tired of hearing it by the time you get to the eighth period class because they're going to have heard it from every teacher, but they wanted us to go stand in front of the kids and go through all the emergency procedures. This is what we do for a fire.

Robyn Semien

For every period?

Melissa Falkowski

For every-- this is what a code black is. This is what we do--

Robyn Semien

For two days?

Melissa Falkowski

For two days, we went over the procedures with the kids.

Robyn Semien

Why did you have to do it with each and every class?

Melissa Falkowski

Because they wanted to make sure that the kids knew the procedures, that it was ingrained in their mind and that they knew. So if they were absent on a silver day, they would get it on a burgundy day.

Robyn Semien

School colors, silver and burgundy. They're on an alternating schedule. Melissa says her kids took the drill seriously.

Robyn Semien

On a scale of 1 to 10--

Melissa Falkowski

I would say we were totally prepared, like a 10.

Robyn Semien

The school told every teacher to cover the tall, rectangular windows on their classroom doors with paper, and leave the paper up all year. Just in case if there were one, it would make it harder for an active shooter to see in. That's a lesson from previous shootings. Get out of sight.

Before Columbine, very few schools did active shooter drills. Now, nearly 20 years later, most of them do. Ashley Kurth teaches culinary at Douglas. She's levelheaded, pragmatic, like a person who's spent years working in busy restaurant kitchens, not losing her cool, which she did. Ashley remembers being trained with the other teachers on the new procedures last year. It started with them listening to 911 audio from Sandy Hook.

Ashley Kurth

The audio is of, I believe, if I remember correctly, it's of the front office and one of the ladies that called in when the shooter is outside the door. And you can hear her, like-- her voice drops when she's like, he's right outside, he's right outside. And you can hear the dispatch officer telling her, you know, don't move and be quiet.

Robyn Semien

Hide, lock down. It's probably the most common response in schools all across the country. But out of Sandy Hook, another lesson. Schools told teachers, keep your classrooms locked all day, every day. Again, Melissa.

Melissa Falkowski

That's kind of what they told us as they told us about Sandy Hook, how he went to the first classroom, the door was locked. He went to the second classroom, the door was locked. He went to the third classroom, the door was unlocked. And he stepped into that classroom, and he took advantage of that opportunity.

And that's what I told my kids when we were preparing. I told them, I know it's going to be really annoying that the door's always going to be locked and you're going to have to knock. But I told them what they had told us in the training. And I said, I will not be the third door. Like, I will not be that third door.

Robyn Semien

The details of this are not exactly right. At Sandy Hook, it was the front door and bathrooms that were locked. The classrooms weren't. But the lesson is the same, keep your door locked at all times.

Other details got hammered home, like what to do if a fire alarm goes off during a code red. The thinking on this is a lesson from the Jonesboro Middle School shooting in Arkansas 20 years ago. There were two shooters, both kids. One of them pulled a fire alarm to get the school to evacuate to a field, where from the woods, the boys shot at them. Five people died.

In the training at Douglas, they addressed this exact thing. If a fire alarm and a code red happen to coincide, ignore the fire alarm, mind the code red. Ashley told her students--

Ashley Kurth

The code red drill trumps all. If you hear a fire alarm go off, you stay put.

Robyn Semien

The main question from students, both Melissa and Ashley told me, what if I'm in the bathroom and I hear gunshots? What do I do then?

Melissa Falkowski

We told them to run. If you're out in the hallway and there's a code red, you have to find a place to hide yourself. So you either find a place to hide or you run, and you keep running, and you don't look back.

Ashley Kurth

You run. You run as far away as you can and as fast as you can away from the sound.

Robyn Semien

Unlike Melissa, Ashley had been through this kind of training before at a school she taught at before Douglas. That school had a drill that really freaked Ashley out, with very loud, realistic sounds of gunfire. Ashley says there were blanks.

Ashley Kurth

The officer would walk around with blanks, and they would shoot. If the door was open, they'd go into the room and say, you're all dead in here.

Robyn Semien

Surprise drills with blanks, while not the norm, appeal to some schools who say there are benefits to learning how you'll act under pressure. But surprise drills with blanks are controversial. For one thing, they're disturbing.

There have even been lawsuits about them. In one, a teacher claims she got PTSD after a man in a black hoodie came into her class, pointed a gun to her face, fired, and said, you're dead. The teacher heard a pop. She smelled smoke. She really thought she'd been shot. She had no idea it was a drill.

I talked to several school safety experts about these drills with blanks, these surprise drills that are hyperrealistic. None of them thought they're a good idea. One guy who trains teachers using video simulations told me that teachers who've been through one of these surprise drills perform worse on his simulations than teachers who have no training at all. They forget crucial steps, like calling the police, and commit more dangerous mistakes. Some find the blanks so upsetting they can't even finish the simulations.

And there's a more basic problem with these surprise drills. If you know one is coming and you hear shots, how can you tell if it's a drill or the real thing? At Douglas, Ashley and Melissa both thought this was the kind of drill they'd have, unannounced with a fake shooter firing blanks. Ashley told her students that's what they should expect.

Ashley Kurth

Oh, yes, 100%. I told them, I said, it can happen at any point in time. So just be prepared that no matter which classroom you're in or where you're at, this could take place.

Melissa Falkowski

They said it was going to sound real and feel real. I now have another faculty member who was at another high school in the district, and they did the active shooter training at her school, and they used blanks. It was simulated, and it felt real.

And so that's why a lot of people were like, is this the drill? Is this not the drill? But when you look at the time that it occurred, they don't run a drill at 2:25 in the afternoon, 15 minutes before we dismiss, and all these buses have to run kids all over the district.

Robyn Semien

Was that a question in your mind right away, like it's too late for a drill?

Melissa Falkowski

Yes.

Robyn Semien

Which brings us to the day of the shooting. At 2:20 in the afternoon on Valentine's Day, a former student with an AR-15 began down the hallway of the first floor of the building that everyone calls the freshmen building. In an adjacent building, Ashley's culinary class had just finished their shrimp scampi lab. They were plating and cleaning up.

Ashley Kurth

I'm standing next to my door, pulling my doorstop out. I hear two pops. It was not rapid fire. It was just like a pop, pop. I'm not startled by it, because, I mean, it's Valentine's Day. And you don't know if it's, like, a balloon popping or what. And then the fire alarm went off very quickly.

Robyn Semien

The fire alarm. Dust set it off, dust from acoustical tiles hit by a round of gunshots. No one knew that at the time. Melissa, in a building farther out than Ashley's, didn't hear any pops, just a fire alarm. She went into action running that drill, the fire drill.

Melissa Falkowski

The fire alarm goes off, and I counted the kids as they left the room. I was the last one to leave. I closed the door. It was already locked because I leave it locked. Out the door with my phone, my keys, and my folder. Those are like the three most important things-- my phone, my keys, and my folder.

Robyn Semien

Her emergency folder. That's the training.

Melissa Falkowski

I went out the doors. The security person who's posted outside my hallway, she's there. And I said, oh, what's going on? Because they have walkie talkies. I don't. The security personnel have walkie talkies. So she said, someone set off a firecracker in the 1200 building. And I said, OK. And I turned to two other teachers and I told them.

And then as soon as I finished saying that to them, she yelled out, no, go back. It's a code red. Go back. It's a code red. And so we called to the kids, and I turned around and went back to my room, which was right there, opened up the door, and kids start streaming in.

Robyn Semien

But was this a real code red? Melissa didn't know. She knew a fire alarm could go off during a code red, but the whole thing was confusing.

Melissa Falkowski

Well, it was weird because we'd actually had an actual fire drill earlier in the day, like our planned, scheduled, monthly drill had occurred that morning. So it was weird that it was going off again because they don't do them in the last period of the day. And so I knew it was something, but I didn't think it was a serious something. I thought it was like-- the culinary was cooking with oil that day. So who knows.

Robyn Semien

Because that will sometimes set off the fire drill.

Melissa Falkowski

Of course will set it off if they burn something or whatever, so.

Robyn Semien

Are there other things that set a fire drill? Oh, well, kids sometimes probably pull it.

Melissa Falkowski

Yeah, sometimes kids will pull it. Sometimes there could be a faulty-- that's why our system gets inspected all the time. It just depends. But most-- I don't want to say mostly it's culinary, because Ashley Kurth will kill me, but a lot of times it's culinary. One time we went outside three times in one day because of the culinary class-- three times.

Ashley Kurth

Yeah. I mean, we have three smoke detectors in my room. So if you walk underneath it with a pot of boiling water, you will set the fire alarm off. That's kind of like the joke of our school.

Robyn Semien

Teachers at Douglas knew that code red trumps a fire drill. They even had a plan for how to straighten that confusion out-- make an announcement, clarify the code red. On that day, an assistant principal, Mr. Porter, did that.

Robyn Semien

Was there an announcement?

Melissa Falkowski

There was, but a lot of people were already out of their room, so they didn't hear it.

Robyn Semien

In culinary, Ashley heard the code red. She's not sure about it, but she's going through the motions. She goes to her door to pull it shut. And as she does--

Ashley Kurth

Two boys come running around the corner, and they're-- just they look terrified, and they're screaming, it's a shooter, it's a shooter.

Robyn Semien

She pulls them into her classroom, tells them to get in the storage closet with her students. But she's still thinking drill, right? It must be. It must be for practice. Even seconds later, when she hears--

Ashley Kurth

Pop, pop, pop, pop, pop, pop, pop, pop, pop. And to me, I'm like, OK, that's not what I experienced in the first drill just because of the rapid succession that was happening. At the time, I was like, maybe they're uppin' their game on that.

Robyn Semien

It's unclear how many teachers thought like Ashley and Melissa did, that this was not a real code red, but the promised code red drill, and if this cost anyone their life. I spoke to the Broward County chief of staff in charge of organizing the district's safety upgrades where Douglas is. He said he didn't know any teachers at Douglas came out of that training expecting an unannounced drill with blanks. But eight of 14 teachers I spoke to said they were anticipating what Melissa and Ashley were, a surprise active shooter drill using blanks.

After those two boys tore around the corner yelling, it's a shooter, it's a shooter, Ashley stood for another second in her doorway, still confused. Then she glanced to her left all the way down the hall to a set of open doors, the face of the freshmen building.

Ashley Kurth

I see like, hundreds of kids running out of the freshmen building looking terrified. When you see terrified kids running like that and they're not-- there is no rhyme or reason. It was chaos. And then you hear-- you can hear the gunshots. And it's just-- that is not what the drill was.

Robyn Semien

She knew it was real.

Ashley Kurth

For like the next 90 seconds, as kids are running by me, I'm just screaming at them, keep running. Don't stop.

Robyn Semien

She shouted back to her kids, stay put and get down. She's still in her doorway when she realized there's another group, a smaller group.

Ashley Kurth

Kids that are running towards the freshmen building.

Robyn Semien

Oh, really?

Ashley Kurth

Yes. I was grabbing them and just pulling them into my room.

Robyn Semien

They were following instructions. Remember, if you're not in a classroom, run. Keep running away from the sound.

Robyn Semien

How is it that kids are running towards kids running the other way?

Ashley Kurth

Because the way that the gunshot sounds were ricocheting off the media center area, the quad, it sounded like there was shooting coming from that direction as well, which is why kids were running in the opposite direction.

Robyn Semien

Wow.

Ashley Kurth

To give you an idea, I had 29 students that were present that day with myself. And by the time we were finished, there were 65 total bodies in my room.

Robyn Semien

Wasn't the drill to shut the door and not let people in?

Ashley Kurth

Yes, it was. [LAUGHING] Yes, it was.

Robyn Semien

Then what happened?

Ashley Kurth

There were terrified people running and I just-- I could not, in all consciousness, leave them be like that.

Robyn Semien

Ashley wasn't the only teacher to stand in the doorway and say to hell with what she had been taught. You can choose to follow the protocol or follow your instinct. For some teachers, it wasn't a choice at all.

In her classroom, Melissa got her attendance sheet out of her emergency folder. She counted 17 of her 25 students, and two from a different class she'd pulled in from the hallway. The group was small enough to fit in a supply closet, so Melissa told them to leave their backpacks out of sight, as she'd been taught, and move there. In the closet, it was hot and dark, except students' faces lit by their cell phones. Melissa had her phone out too.

Melissa Falkowski

There's a group text between me and three other teachers in the English department because we're friends outside of school. And my friend Stacey, who is on the third floor of the freshman building, she texts-- she sent a text to us that says, there is a shooter. There's a shooter in my floor.

And so my friend Sarah says, drill or actual? And she says, actual, my window is blown out. And then she told us she had been grazed by a bullet. She was grazed in her arm by a bullet.

Robyn Semien

Oh, my god.

Melissa Falkowski

And I didn't hear from her for a while.

Robyn Semien

An hour went by.

Melissa Falkowski

We heard noises in the hallway. We got really quiet. I had the flashlight part of my phone on so that we could kind of like illuminate the closet without having the light on. And when I heard the door open-- but it sounded like it was opened with a key. And so then I could hear movement in the room. And then somebody--

Robyn Semien

And that's comforting or not?

Melissa Falkowski

I mean, not, because you don't know what the hell is happening. And the police-- and then the police officer said, this is the police. Is anyone in here? And then there was kind of like a pause. And then they're like, this is the police. Is anyone in here? And I was like, guys, I'm going to open the door because--

Robyn Semien

Someone says, this is the police, is anyone in here? And your first thought is, it really is the police, or still you're not sure?

Melissa Falkowski

I'm still not sure. The first time they said it, I'm not sure what I should do. Am I supposed to open the door?

Robyn Semien

They didn't cover that in training.

Melissa Falkowski

Very slowly, the handle, and I opened it really slow because even if it is the police, they have weapons too, and they're looking for the shooter. So I know they have their weapons drawn.

Robyn Semien

She really just had to guess about whether to trust this was a cop and not a group of shooters saying they were cops.

Melissa Falkowski

And so I just very slowly opened, pulled on the handle, pushed it open and said, we're in here. We're in the closet. And then they started giving us instructions. Come out with your hands up.

Robyn Semien

Melissa told me that Ashley was one of five people she knew who had broken protocol that day, by holding their doors open longer than they were supposed to.

Melissa Falkowski

And they even did that on the third floor when they knew something was wrong. And my friend Stacey held her door open until she was like, locked eyes with the shooter, and yells to Scott Beigel to close his door, and grabs the handle with two hands and pulls it closed. So her door was open up to the moment he started, like, shooting bullets down the hallway.

Robyn Semien

Stacey is the teacher whose arm was grazed. She survived. Scott Beigel in the room next to Stacey's did the same thing Stacey did, waited a little with the door open. He's one of the 17 who died that day, standing in his doorway.

There's very little evidence about whether school shooting drills of any kind actually work. The data doesn't exist. School shootings, for how much we think and talk about them, are still statistically rare. But now, Melissa and Ashley have been in that rare situation, the one that's hard to study.

And they both told me that having a playbook for what to do helped. Now I lock my door. Now I count the kids in my class. Now I move us all to a closet. But they also both had ideas coming out of this, about ways they could have been better prepared. Melissa, for instance, wanted trauma kits with gauze in every classroom and training on how to treat bullet wounds with it. Gauze actually has saved lives in mass shootings.

I really wanted to find some expert to weigh in on Douglas, to tell me, did the teachers' training help? Did more kids survive because of it? What might have worked better?

Cheryl Jonson researches what's effective in these drills at Xavier University and is a training instructor for ALICE, one of two big companies in the US that train schools how to respond to active shooters. ALICE has its own way of doing things, just like the other big outfit, Safe Havens International, has its own way of doing things. There's no one single way, no agreement on what's best.

Cheryl Jonson didn't want to get into the specifics of what happened at Douglas, partly because it's still too soon. The investigation isn't done. But she did talk to me more generally about some of things I knew they'd done at Douglas, like papering over windows. Cheryl doesn't think it helps much.

Cheryl Jonson

It's 2 o'clock on a Tuesday. The shooter knows you're in your classrooms.

Robyn Semien

Also, code red, all the codes, their colors and meanings. The consultants I talked to said no to this too.

Cheryl Jonson

I'm a big advocate for not using codes at all.

Robyn Semien

How come?

Cheryl Jonson

If I say "code red," it takes a split second for your brain to go, OK, code red means bad, means active shooter, means I have to do this versus if I say there is a gunman in the school.

Robyn Semien

Keeping classroom doors locked, resounding yes. But the idea that this is all you do, that you lock the door and put every kid under a desk, all the consultants I talked to said that's outdated. Cheryl says people need many more options, many more ways to respond to a shooting.

Sometimes you stay in your room. Sometimes you evacuate, like if you're far enough away from the shooter or in an open space with more exits, like a cafeteria or a gym. As a last resort, you fight. Basically, trust your ability to make a decision.

I told her about Ashley Kurth, how she had stood in her doorway, grabbing up dozens of scared students. Remember, it was a break from her school's protocol. Cheryl's such an advocate for thinking on your feet. I wondered if she maybe believed Ashley did the right thing, pulling in kids.

Cheryl Jonson

The problem with this-- unless you're there, you don't know what exactly happened. Now, did she probably save lives? Probably. And in that situation, did it work with the gunman being in a different building? Yes.

Robyn Semien

One thing that was part of the training at Douglas was barricading your door, basically pushing lots of furniture up against your classroom door. But Melissa and Ashley didn't do it. Seems like very few teachers did. Though if Ashley had done it, if she'd followed the protocol, locked and barricaded her door right away, it would've been way harder to pull all those kids into her room from the hallway. She'd have to unbarricade herself first. Fewer kids would have made it in.

Reporting on this for several months, I knew what I was looking for, something concrete to tell my daughter's school. My daughter's nine, fourth grade. Last year, she did a traditional lockdown at her school, squat and hide. But when I asked her what the drill was for, she said, I don't know exactly. They didn't say. It's not great.

I keep thinking about this one shooting, the Red Lake Indian Reservation shooting, and how in that one, a classroom of students did a traditional lockdown, squat and hide, because they practiced it, and how an investigator on that case told me that drill did not help them at all. They'd have been better off without it. And the researcher who told me we should not do drills in school, period. It's too traumatizing for kids. We don't pretend to crash on an airplane. We just deal with the possibility of crashing by hearing some instructions.

Where I come down on this-- I don't agree with no drills at all. I want my daughter to know everything. I want her to know about barricading, and I want her to know about running and fighting back. I want her to know about active shooters because it's a thing to reckon with. I want her to know there's nothing that can keep her completely safe because it's the truth.

One more thing I'd say to my daughter's school, Cheryl's point about don't say codes. Call it like it is. I don't want someone to come over an intercom and tell my daughter code red. I want someone to say, listen up, there's a person with a gun in our school. Of course, I never want someone to say that at all.

This year at Douglas, there are new gates, new fences, new cameras, gym bag searches, key card entry for staff, gauze-filled trauma kits in every room, 15 campus monitors compared to five last year, three school resource officers instead of one. And they already did a code red drill, only this time there was no confusion about when it would be. The school called parents, told all the students and teachers in advance. When it started, the principal came on the PA and told everyone, OK, here we go. And this is our code red. And try to breathe. Keep breathing.

Only real surprise since school started, if you can call it that, the fire alarm. It's gone off seven times so far this year-- malfunctions, maintenance, a special ed kid pulled it twice. Two times it happened right before school got out. Melissa said the first time it happened a week in, she cursed. Students cried.

One student, Julia, froze. Julia, Melissa said, you're OK. Am I? Julia said.

What the school does not do during the fire alarms, evacuate, like they're supposed to. No one goes outside to the parking lot. No one jokes about culinary. No one moves. Not a single class evacuates.

Melissa says it's too scary to be out there standing in the parking lot like that, vulnerable. What if there's a sniper? It's what they know now. Drills have blind spots.

Ira Glass

Robyn Semien is one of the producers of our show. Coming up, a couple returns to the worst thing that ever happened to them, over and over again. Why? In a minute, from Chicago Public Radio, when our program continues.

Act Two: Keep Breathing

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose a theme, bring you different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's show, "Before the Next One." Now the mass shootings have become the new normal in our country. We have stories of people preparing for the next one in various ways. We've arrived at act two of our program, act two. Keep breathing.

So there's a whole infrastructure that springs into action every time a mass shooting occurs. There's Red Cross, fire and police departments, SWAT teams, therapy dogs, the Billy Graham prayer truck. But now, there's also a group of people who show up in the immediate aftermath for more personal reasons. These are the parents of kids who've died in other mass shootings.

And what they do at these shootings is so simple and kind of amazing to hear. Producer Miki Meek talked with two of these parents. It's a couple named Sandy and Lonnie Phillips. Their daughter, Jessi, died when a gunman opened fire in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado back in 2012. And since then, they have organized their lives to be able to reach out to other parents like themselves. Here's Miki.

Miki Meek

Sandy and Lonnie Phillips have traveled to eight mass shootings since Aurora. It started with Sandy Hook and Isla Vista, San Bernardino, Orlando, Las Vegas, Sutherland Springs, Parkland, and then Santa Fe, Texas, which is where I met up with them in May, right after a student walked into the high school and killed 10 people. They pulled up in front of the school in their truck. Even though they have done this a lot, Sandy told me the discomfort and awkwardness they feel about showing up like this in a community has never gone away.

Lonnie Phillips

Ready for this?

Miki Meek

But in Santa Fe, they just launched themselves in anyway. They're each wearing a big button with a photo of their daughter, Jessi, smiling. A memorial had just gone up on a big, grassy lawn out front. There were 10 wood crosses, each with a red heart and a photo of the student or teacher who had been killed. People were starting to leave teddy bears, flowers, and balloons.

What the Phillips do here is just talk to whoever wants to talk. They figure that'll lead them to families they might be useful to. And within seconds of getting out of their truck, they bump into a dazed teenage girl wearing shorts and a Santa Fe High School soccer T-shirt.

Sandy Phillips

Excuse me, how are you doing?

Girl

I'm not OK.

Miki Meek

And here, the sound gets muffled because Sandy's tiny mic gets crushed when they hug. It's the main sound I remember from that day.

[TAPPING ON MIC]

Sandy Phillips

We're just so sorry this has happened to you and your friends and your families and your community.

Girl

Thank you so much.

Miki Meek

Another girl, a junior with light brown hair pulled back into a ponytail, walks up to them and stares at their buttons.

Sandy Phillips

We lost our daughter in a mass shooting six years ago.

Girl

Is that her?

Sandy Phillips

Mm-hmm.

Girl

She's pretty.

Sandy Phillips

Thank you. She is. Inside and out, she was lovely, just like your friends.

Miki Meek

Sandy is good at making people feel comfortable. She has a round, warm face, framed by a gray bob. She's maternal and keeps her comments caring and brief.

Lonnie stands right next to Sandy with his arm around her. Sandy's the one who mostly talks to the kids, but he's always by her side, listening intently. His presence helps her do this. He looks out for her, sometimes running ahead to start the AC in their truck before she climbs in.

Sandy Phillips

Hi.

Woman

My name's Tracy.

Sandy Phillips

Hi, Tracy.

Woman

I hear you had a daughter--

Miki Meek

I was surprised at how quickly people opened up to the Phillipses.

Sandy Phillips

Jessi.

Woman

Jessi? Beautiful.

Miki Meek

The girl who said Jessi was pretty, she started telling them that she escaped the shooting by hiding behind a building with other students. Now, she just wanted to stay at home. But at home, all she could think about was the shooting. Scenes from that day kept replaying through her head. Sandy doesn't miss a beat here.

Sandy Phillips

Over at the victims' assistance, they have trauma therapists over there. I recommend strongly that any of you kids, really think about stopping by the victims' assistance.

Girl

I will.

Sandy Phillips

Do some trauma therapy. OK, honey.

Girl

Thank you so much.

Sandy Phillips

You're welcome.

Miki Meek

The Phillipses don't make money off this. They're volunteers, and they're not wealthy either. They're retirees living in a 245-square foot trailer, surviving off of modest savings and social security. Sandy is 68 and used to work in tourism for the city of San Antonio. And Lonnie is 74. He used to own some car lots.

Sandy Phillips

So have you guys met?

Girl

Yes.

Miki Meek

One thing I quickly realized going to Santa Fe is that there are now so many of these mass shootings that they become grim reunions for all the people who show up to them as part of their jobs or volunteer work.

Sandy Phillips

Are you from Las Vegas?

Miki Meek

Sandy and Lonnie ran into an emergency responder from the Las Vegas shooting, and then bumped into this other guy who travels around, putting up all those white crosses you see at almost every mass shooting. He made one for their daughter, Jessi, in Aurora too. Standing on the patchy brown grass next to the crosses, Lonnie interrupted him to do this thing he and Sandy do a lot.

Lonnie Phillips

Sign, 1:11.

Miki Meek

They suddenly call out the time.

Lonnie Phillips

We have a 1:11, 11:11, and we're talking to you at 1:11. So it's a sign from our daughter.

Miki Meek

11:11 is a thing. A lot of people see it as an auspicious sign or a time to make a wish. And it was a lyric in one of Jessi's favorite songs.

Lonnie Phillips

If we get 11:11 twice a day, we know we really had a good day.

Miki Meek

They told me, I know it's silly, but I take it as a hello or a god wink. It helps.

Sandy Phillips

Hello. What's your name?

Cindy Evans

Cindy Evans.

Sandy Phillips

Cindy, Cindy?

Cindy Evans

My son is in high school here.

Sandy Phillips

Oh, I'm so sorry.

Miki Meek

As the day went on, people kept dropping by the memorial in front of the high school. Parents and students stood huddled together, staring at the crosses or writing messages on them. It was quiet and hot and still. There was a low generator hum from the gigantic Billy Graham ministry truck set up in the parking lot. And then all of a sudden, this young guy started wailing. Sandy made a beeline for him.

Young Man

It's too much, man. It's too dang much. I'm so angry.

Miki Meek

He immediately threw his arms around her.

Young Man

Why this thing keeps happening.

Sandy Phillips

Here, here, here, here. Put your arms around me.

Young Man

[SOBBING]

Sandy Phillips

It's OK. It's OK.

Young Man

[SOBBING]

Sandy Phillips

It's not OK. It's not OK. Let it go, let it go, let it go, let it go. Just cry your heart out.

Young Man

[SOBBING]

Sandy Phillips

Cry your heart out and get your anger out on here, on here, on here.

Young Man

[SOBBING]

Sandy Phillips

I'm so sorry. Oh, god, I'm so sorry.

Young Man

It makes me wish I could've done something.

Sandy Phillips

OK. It's OK, honey. You're doing it now.

Young Man

[SOBBING]

Sandy Phillips

You OK?

Miki Meek

He graduated last year. There were crosses set up for three people he knew well. One of them was a teacher named Ms. Perkins, who he really loved. He said she always tried to be strict with him but could never keep up that front for very long.

Sandy Phillips

Just breathe. Take a nice, deep breath.

Young Man

[SOBBING]

Sandy Phillips

Take a nice, deep breath.

Young Man

[SOBBING]

Sandy Phillips

OK, OK. Breathe with me. [EXHALING]

Young Man

Thank you.

Sandy Phillips

There you go.

Miki Meek

After a few minutes, he's caught his breath enough to talk. He tells Sandy he wants the shootings to stop. He wants to take action somehow. And then he suddenly switches gears and starts spilling out his feelings about guns and gun control.

Young Man

Nowadays with the violence that is going on in this world, taking guns away is not going to change that because it's just like drugs. They make drugs illegal and are still able to get drugs.

Miki Meek

He plans to get a concealed handgun license when he turns 21 later this year. The Phillipses are actually gun owners too. They have a 12-gauge shotgun. They believe in the Second Amendment. But they're also advocates for universal background checks and tight regulations on the types of guns, ammunition, and accessories, like bump stocks, a person can buy.

However, Sandy says they don't push their political beliefs on survivors when they're doing outreach. Their primary goal is to support. But it's impossible for grieving parents to avoid the politics around guns. There's a whole movement of conspiracy theorists who believe that the US government stages mass shootings to make guns look bad.

Sandy Phillips

We were told by Alex Jones that our daughter never existed.

Miki Meek

Alex Jones, of course, is famous for saying that mass shootings are fake. He's now a defendant in several defamation lawsuits. When the Phillipses ran into him face-to-face at a gun control event, he accused them of inventing their entire story.

Sandy Phillips

And then two minutes later, he's saying, your daughter's still alive, and she's living in the Bahamas, and she's living the high life. And you're crisis actors, and you're paid by the Obama administration, and da da da. I'm listening to him, just going, you are so absolutely crazy.

Miki Meek

Lonnie got into it with Jones, stood right in front of him. It looked like a shoving match was about to start, until Sandy stepped in and broke it up. I reached out to Jones through one of his lawyers, who declined to comment. The conspiracy theorists, known as truthers or hoaxers, troll families of victims on social media immediately after any mass shooting.

This can get dangerous. After the Phillipses' son gave interviews in Aurora, he got death threats and had to get the FBI involved. The man who was threatening him ended up in jail. So hoaxers are one of the things the Phillips has warned parents about. They tell families to brace themselves.

After watching Lonnie and Sandy in Santa Fe, I wondered why in the world they were throwing themselves back into this setting, reliving their worst moment over and over again. The answer, of course, starts with their daughter's shooting. They got the news in the middle of the night when they were asleep at their home in Texas.

This was back in 2012. And their daughter, Jessi, was in college at the time. She got to see the new Batman movie, The Dark Knight Rises, with one of her friends at a multiplex in Aurora, Colorado. About a half hour after the movie started, Jessi's friend called Sandy from the theater.

Sandy Phillips

The minute I picked up the phone, there was screaming, just horrible screaming in the background, panic. And he said, there's been a shooting. And I was like, what is he talking about? Because Jessi had been at a mall in Toronto almost seven weeks before, where there was a mass shooting.

Miki Meek

This was a coincidence. Jessi had left a food court in a mall just three minutes before a man walked in and opened fire.

Sandy Phillips

So my first thought was, this isn't funny. But he's not a prankster. And I said, are you OK? And he said, I think I've been hit twice. And it was when he said that that I went, why isn't Jessi calling? And I knew something was really wrong. He said, I tried.

Lonnie Phillips

And that's when I woke up because the scream was so loud. It was so horrific and something I never heard before.

Miki Meek

Lonnie found Sandy in the living room, sliding down a wall. He picked her up and took her to their couch, where he held her. Jessi was one of 12 people killed that night. Another 70 people were injured. And then five months later, there was another mass shooting, Sandy Hook, where 20 first graders and six educators died.

Days later, the Brady Campaign to prevent gun violence contacted the Phillipses. They were reaching out to families from other mass shootings and asked if they'd be willing to travel to Newtown to talk to parents there. Sandy says they didn't even have to think about it. They immediately said yes, because they wished they'd had someone to talk to right after Jessi died.

But when they arrived at a community center in Newtown, Sandy says they felt nervous and uncomfortable. Maybe they were intruding. They weren't sure if these parents would feel angry or grateful about their presence.

Sandy Phillips

It's like walking into a funeral of people that you don't know. And I remember saying to my husband, when we walked in the room and I saw their faces, I said, that's what we looked like five months ago.

Miki Meek

What does that look like?

Sandy Phillips

Pff. They're hanging on to each other. They've been crying, so their eyes are red. They're walking almost robot-like. Their bodies are moving, but they're not really there. I realized, that's what I looked like just five months ago. But it also made me realize, this is exactly what I want to be doing.

Miki Meek

She wanted to help these parents acclimate to their new reality. Looking back, Sandy says it was probably too soon for them to be out there trying to comfort other parents when they were still so raw. But the Phillipses said there was also a strong and instant sense of kinship that they couldn't turn away from.

While they were there, they ran into parents from other mass shootings, too, parents from Virginia Tech and Tucson. These parents had lost kids suddenly and violently in places where they thought that they were safe. The Phillipses now had parents that they could lean on too.

This was the moment that launched the Phillipses into what's become their life work. They could see the need. There are no experts on what to do when your child dies in a mass shooting. The only experts are the people it's happened to.

So to help them find each other, Lonnie and Sandy have set up an organization called Survivors Empowered. They help families navigate their grief, plus a bunch of other practical things, everything from medical bills and charity scams that use kids' photos to raise money, to how to get your child's body home if you live out of state. However, this new mission was hard for their family and friends to comprehend.

Lonnie Phillips

They want you to move on with your life. They want you to get back to normal. My own brother said to me-- said, you're not the same as you were. I said, let me explain something to you. You're right. I'm not the same person. I never will be. They see it as we're obsessed with this. Well, we are, in a sense. We are obsessed with it.

Miki Meek

The Phillipses and a few other parents told me, because it's so hard for people to understand that the grief never fades, old relationships start to fall away. People you were closest to disappear, which makes this informal support group even more crucial.

What that support looks like over time and what it means to the parents who get it, I've got to see all that when Sandy and Lonnie got to know a couple from Florida who lost their son in the shooting at Parkland. Annika and Mitch Dworet. I met them at their house.

Their son's name was Nick. He was the captain of Parkland swim team and was about to go to the University of Indianapolis on a swim scholarship. He was a six-foot tall blond kid who collected different flavors of Oreos and waited for supreme drops. Mitch said they'd just reached a point where they were becoming real friends. They talked about relationships, shared playlists, and watched Scarface together.

The day of the shooting, Mitch and Annika got phone calls and texts all day from people who said they'd heard Nick was OK. One person said they heard he'd been moved to a staging area for all the students who'd witnessed the shooting. Another said a police officer was giving him a ride home. And then a nurse at a local hospital said she saw a patient who matched Nick's description. But by that evening, the Dworets' still hadn't heard directly from Nick, so they went to an area that law enforcement designated as a meeting area. They sat in a ballroom with other parents and waited.

Annika Dworet

Every time the phone rings, you jump and think it's Nick calling from somebody else's phone. The media was calling you. Do you have any comments? Can we help you find your son? I was just like, yeah. And at 2 o'clock in the morning, we see this FBI car, and then they start pulling one family into a room at a time. And you hear screams from these rooms.

Miki Meek

Then their names were called out.

Annika Dworet

Even walking into that room, you have this tiny little hope that they're going to say, we couldn't even find your son, and that hope of that he was somewhere else. And I keep on thinking, maybe he walked home. And then you do the math in your head, like, doesn't take that long to walk to our house. And then they told us the news that he was gone. He was shot and he was never brought to the hospital at all-- just like a nightmare, just like a nightmare.

Miki Meek

Nick's body was still at the school because he died instantly, and the building was still a crime scene. It'd be two days before they could see him. Annika wanted to look at his injuries. Mitch did not.

Annika says, this is just how her brain works. She's an ER nurse. She needs details. The director at the funeral home, wanting to protect her, called the medical examiner's office to ask about Nick.

And the person that answered the phone said, oh, let me take a look. What's the name again? It's Nicholas Dworet. He's the swimmer. Oh, the swimmer's perfect.

Miki Meek

What does that mean?

Annika Dworet

I think it meant that there was nothing on his face or his head, like he was perfect.

Miki Meek

He'd been shot three times. A bullet in his chest destroyed his heart and lungs.

Miki Meek

Was it helpful for you to see him?

Annika Dworet

Yes, it was helpful. Because your picture in your head, when you hear that somebody has been shot with an AR-15, just so gruesome, so horrible, horrible. And I think to see him and to see on his body where his injuries were made me get it, like he was so peaceful. And he was not in pain. And it made me have a better image of him than the one that was playing over in my mind.

Miki Meek

The Phillipses had traveled to Parkland a couple of days after the shooting. They didn't know the Dworets, but a mutual friend thought they should talk. And so this friend, with Mitch's permission, gave Sandy his phone number. Sandy called and got no answer, so she left a voicemail.

Sandy Phillips

I'm very sorry for your loss. I understand your loss. We lost our daughter. And you can call me any time.

Miki Meek

She let them know that she and Lonnie would be in Parkland for a few more days. Mitch called back quickly. He did want to meet with them in person, thought it would be helpful to talk to another family who'd been through a mass shooting. But he told Sandy the timing wasn't going to work. His house was packed with family in town for Nick's funeral.

Sandy Phillips

And I'm on the phone with him, and ironically, I'm standing right in front of his child's cross. And I said, you're not going to believe this.

Mitch Dworet

She said that she was standing right in front of Nick's memorial. I get chills right now.

Sandy Phillips

And we proceeded to have a talk. And he said, I don't think we're ready to meet with you. And I said, I totally understand. I'm just glad that we're getting to talk. But you do need to know that truthers are already online saying that this didn't happen. He said, what are truthers? And I said, ugh, OK.

Mitch Dworet

I thought like, wow, you kidding me? Crazy.

Miki Meek

Mitch asked her to stop by their house the following day. While Mitch was on board with the Phillipses, Annika had a different take on total strangers stopping by their house.

Annika Dworet

I was more-- maybe more skeptical, like nervous of why are they here? What's their agenda? How can people come and meet with us if they don't want something from us?

Miki Meek

Their house was so crowded that the only private place to talk was their bedroom. Annika and Mitch sat on the bed, Lonnie and Sandy on chairs. Annika remembers feeling a little uncomfortable and thinking to herself--

Annika Dworet

Why am I sitting here? Why I'm not with the family? Who are these people? I don't know them. But I guess it might help. But it was very overwhelming. Like, I can't believe that I have to sit and have this conversation. What is this? This is my life now?

Miki Meek

Was there a point in the conversation where it started to turn for you?

Annika Dworet

Yeah. I think when they said, don't join our organization now, don't fight now. Just take care of yourself and let yourself grieve.

Miki Meek

They asked questions about Nick. And before long, they were just talking. Lonnie remembers Mitch asking if they were religious and if they ever got signs from Jessi. He told Mitch that, like them, they weren't, but they took 11:11 as a hello from Jessi. The conversation went on for three hours.

Annika Dworet

All our friends and family, as much as they did for us and how much love they showed, none of them could have any clue what we were feeling. And here were two people knowing exactly what we were feeling.

Mitch Dworet

They also made me feel a little more confident. I don't know if that's the right word. You're in a club we all don't want to be in. We didn't want to meet you. We wish we would have met under different circumstances, but you have people help you with this kind of grief.

Miki Meek

And a few days later, when the online conspiracies started appearing about Nick, that he didn't exist or that he was living in California, they remembered Sandy's warning. It was still upsetting, but less upsetting because they knew it was coming. They've helped in other ways, too. The Dworets took the Phillipses' advice and got in to trauma therapy right away, both individually and as a family.

Their younger son, Alex, has been through a lot. Nick was his best friend. One of the last things Nick did on the day of the shooting was walk Alex to his English class. Alex was injured in the shooting and sat by a kid who died right in front of him. Annika says managing her grief, along with her son's, has been tough.

Annika Dworet

There was so much attention on Nick, Nick, Nick, Nick, Nick. Everybody came for Nick. The flowers were for Nick. The letters were for Nick.

I felt like I-- if this didn't happen to Nicholas and only this, I could have been there for Alex so much stronger and so much more. So I was afraid that he would get neglected in all that.

Sandy Phillips

I think sometimes children feel like, well, you must have loved that child more than you love me.

Miki Meek

Sandy's son was 25 when his sister died. Sandy tried to talk to him about it, which ended up pushing him farther away. When she talks to parents, she talks about her own mistakes, too.

Eight months after they first met, Mitch is still in touch with Sandy. They text or call each other every couple weeks. Mitch relies on Sandy more than Annika, who unlike him, already has a built-in network of friends she talks to all the time.

Mitch Dworet

And we texted-- I think we texted yesterday. It was 11:11 actually. We texted yesterday.

And I feel like she's still in it. She's still with us. It's someone who we can lean on and give us support. And I, in turn, want her to lean on me. Maybe seeing us get stronger, it gives her energy, too.

Miki Meek

He's right about that. Sandy spends almost every day at her tiny kitchen table in her trailer, fielding texts and phone calls from survivors, and messaging with people on social media who ask for help.

Sandy Phillips

The pain is always there at the end of the day. And when you go to bed at night, when you first wake up in the morning, it's there. But you have a sense of purpose and that helps.

Miki Meek

A little bit of a lifeline or something?

Sandy Phillips

Oh, it's a total lifeline, total-- if I didn't have this work, I don't think I'd be alive, I really don't. And I say that to Lonnie all the time. He goes, but don't you love me enough, kind of thing, to stay alive? I just don't think I would have had the ability to keep going.

Miki Meek

Mitch and Annika told me that when they're feeling stronger, they'd like to do for other families what the Phillipses have done for them. They said, god forbid another shooting happens. But if it does, we'll be out there with them.

Ira Glass

Miki Meek is one of the producers of our show.

Credits

Ira Glass

Our program was produced today by Lisa Pollak and Robyn Semien. The people who put the show together today includes Elna Baker, Zoe Chace, Sean Cole, Damien Graef, Michelle Harris, Chana Jaffe-Walt, Seth Lind, Anna Martin, [INAUDIBLE], Miki Meek, Catherine Raimondo, Nadia Reiman, Christopher Swetala, Matt Tierney, and Diane Wu. Our senior producer is Brian Reed. Our managing editor is Susan Burton.

We had some original scoring in today's program by Matt McKinley. Special thanks today to Andy and Barbara Parker, Heather and Seth Adams, Nicole Hockley from Sandy Hook Promise, Michael Dorn of Safe Havens International, Harvey Shapiro and James Fox at Northeastern University, Carrie Klein, Kate [INAUDIBLE], Joe Eaton, and Jim Irvine.

Our website, thisamericanlife.org, where you can listen to our archive of over 600 episodes for absolutely free. We also have an app that lets you download our entire archive and lots of other features. This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange.

Thanks as always to our programs co-founder, Mr. Torey Malatia. You know, he was watching this documentary on rock and roll in the '60s, but it complained it was taking them forever, forever, to get to The Rolling Stones.

Man

Oh, yeah, it was because you got to get through the doors.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

[MUSIC - BAHAMAS, "NEVER AGAIN"]

Never again, never again will I let you go. Never again, never again will I let you go. Never again. Never again.