687: Small Things Considered

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue: Prologue

Ira Glass

Of all the things in the movies that could happen to you-- and there's so many, right-- I think getting shrunk down to a miniature size-- I think that is one that nobody would ever choose. It seems dangerous. It seems frightening. How Marvel Comics ever thought that shrinking could be a superpower, that is really totally beyond me. Turning yourself into a person the size of a pencil eraser? It doesn't make anything easier. Everything is harder. In the movie Ant-Man, the first time Ant-Man shrinks--

Ant-man

What is this?

Ira Glass

--he's instantly in mortal danger. Water in a bathtub nearly drowns him.

[SCREAMING]

People dancing in an apartment almost crush him with their high-heeled shoes. A rat tries to eat him.

[GROWLING]

It's a ridiculous superpower. The writers actually have to cheat and give Ant-Man a whole second power, mind control over armies of ants, or he'd never get anything accomplished. But these stories of tiny people, you know, Honey I Shrunk the Kids, The Borrowers-- when I was young, I loved the film Fantastic Voyage-- I do get the appeal of them. They give you this feeling of what if. What if I was so small that I could stand between the wafers of an Oreo cookie, that I could climb onto an insect?

Last year, when she was in fourth grade, Chloe thought about this a lot. She's a kid in suburban New Jersey. Now that she's in fifth grade, she finds this a little embarrassing. But last year, every night when she'd go to bed, she'd prepare for the possibility that magic might strike while she was asleep, and that she would shrink down to the size of her dollhouse. Those preparations included--

Chloe

I would sleep on the edge of my pillow. It's like the very top of my head is on the pillow, and then the rest of my body is on my bed.

Ira Glass

That way, if she shrunk in the middle of the night, she would be on the bed and not on the pillow, which seemed way more treacherous to her. She also took a slap bracelet, which can stretch out like a ruler, and positioned the ruler very carefully, like a little bridge, from--

Chloe

The edge of my bed to the edge of my bedside table.

Ira Glass

And why?

Chloe

To walk from my bed to my bedside table where I had the little hammock

Ira Glass

The little hammock, which she made for herself to sleep on, which is basically a bracelet of intertwined rubber bands suspended in air on a frame of Q-tips.

Chloe

And then I also had a little couch, and the couch was on the bedside table. So you walk past the ruler. You turn left, you'll see the couch. And if you go a little beyond that, you'll see the hammock.

Ira Glass

Under the hammock was a calculator that she could step on, like a little footstool, to get up onto the hammock. And next to the couch was a Post-it folded in half with a note to her parents explaining that she had shrunk, all ready to be unfolded when this really happened to her for real. And finally, every night when she went to bed--

Chloe

I took some of the really important things to me, put them in a blanket, and then held onto the blanket every night, hoping that it would turn small with me.

Ira Glass

So what would be wrapped up in the blanket?

Chloe

My stuffed animal, Boo, my cat stuffed animal, one of my books, and a couple other stuffed animals.

Ira Glass

And were you hoping that this would happen, or were you fearing that this would happen, that you would get small? [BEEPING]

Chloe

I was both.

Ira Glass

That beeping that you're hearing-- Chloe was being recorded on a telephone whose batteries started dying at this point in the interview, making that beeping noise.

Ira Glass

Tell me the hope; tell me the fear.

Chloe

The hope because then I would get to live in my dollhouse, which, it had a little swing on the porch. It's cool. And I wouldn't have to watch Netflix with my sister. And every popcorn would be a meal.

Ira Glass

So that's the hope. What was the fear?

Chloe

The fear was my parents wouldn't be able to hug me. I might not have electronics. I wouldn't be able to see my friends, because I would be tiny. And I wouldn't be able to go to the pool.

Ira Glass

[LAUGHS] You wouldn't be able to swim anymore.

Chloe

Yeah, well, my mom could just set up a little bowl.

Ira Glass

Yeah. I was going to say, she could just take a tray of water and just put it out for you.

Chloe

Yeah.

Ira Glass

Once you start to think about the world this way, small stuff can become really transfixing. The sheer tinyness of tiny things can have a kind of mesmerizing power to it. We were talking about this at our office last week, and Bim took the most extreme stand on this. I dragged her into the studio to talk about this.

Bim Adewunmi

I just like generally small things. If there is a small version of a thing, I am interested in seeing it or reading about it or hearing about it.

Ira Glass

It's Bim who told me about the radically tiny tubs of Vaseline you can buy, which have the exact design of the bigger jars.

Bim Adewunmi

It's about the size of my thumbnail, maybe my thumbnail and a half. They're very small. They're very cute. They don't look like they're real. They look like ornaments that you might hang from a Christmas tree.

Ira Glass

And what you like about them is--

Bim Adewunmi

What I like about them is just how small they are. They seem almost pointless. You can find Vaseline in any number of other sizes. The fact that this exists-- I think it feels like somebody-- yeah, it was just a pointless gesture. Let's make Vaseline even smaller. Can you imagine them looking across at one another and kind of going, hey, should we make this smaller? And someone said, there's no need. And they were like, precisely.

And I think small things, by nature, are whimsical. They just feel like, oh, you didn't have to be. You didn't have to exist, but here you are. And that's what makes them kind of joyful.

Ira Glass

They're just things for the pleasure of smallness and staring at smallness.

Bim Adewunmi

It's like when you look at broccoli, and you think, oh, I'm a giant, and this is a small tree. It's that feeling. I'm almost 40.

[LAUGHTER]

Ira Glass

Do you still have that feeling? You'll look at a broccoli, and you'll think it's like a small tree?

Bim Adewunmi

I don't still have that feeling. I used to have that feeling when I was a child. I will not be mocked. [LAUGHS]

Ira Glass

No one has mocked you yet.

Bim Adewunmi

Your face.

Ira Glass

Well, today on our program, "Small Things Considered," we have stories of people overlooking what is so great about the tiny, the minuscule, the peewee, the bite size, and the teensy-weensy. Also, some very dramatic examples of the power of smallness, including, for instance, the power to end health insurance as we know it for millions of people.

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. My voice is affected by some sort of tiny, tiny bug this week. Stay with us.

Act One: Coming Up Short

Ira Glass

Act 1, Coming Up Short.

So a while ago, we got an email from a physician who was starting to see a trend that disturbed her, among her patients. She wanted us to look into it. We thought our contributor Scott Brown would be the best person for the job for reasons that'll become clear as he proceeds. Here's Scott.

Scott Brown

So this doctor told us that all of these parents have been coming to her, scads of them-- she used the word inundated-- with the same problem. Their kids were short, not dramatically short. They were just below average height for their age. We're talking 9-, 10-, 11-year-old kids. And what these parents wanted was for this doctor to prescribe them human growth hormone injections to make their kids taller.

These are daily injections that cost tens of thousands of dollars a year. It's usually affluent privileged families, this doctor says, who already have all the advantages. She went as far as to call the desire for growth hormone among these folks an epidemic.

Short Throat

Because I've had parents come to me and say, "Everyone I know is on growth hormone." That was an actual quote. Everyone I know is on this stuff. Or, it's all the rage in this anonymous community, a very affluent community.

Scott Brown

This doctor want it to be completely anonymous, by the way. She feels like she's whistleblowing. In fact, this isn't her real voice. We swapped her voice for an actor's in our recording of the interview. Since I can't identify her, I'll refer to her from here on as Short Throat. All we can say is she's a pediatric endocrinologist-- that is, a children's doctor, specializing in stuff like diabetes, thyroid problems, and growth.

She says she got into medicine to treat sick kids, but fully half of her patients are coming to her just for the growth part.

Short Throat

So parents will find out one kid is being treated and assume that their child, because they're below average, needs it too. Like, oh, if they're doing it, then am I going to be missing out? In fact, I think the phrase one mom used was something like, I'm just trying to be proactive and worried, I don't miss my window of opportunity.

Scott Brown

That window is real. Parents have to start their kids on the drug by the time they're hitting puberty. Short Throat has been practicing for about seven years, but she works closely with other doctors who've been at it for decades.

Short Throat

And they do say that it's gotten much, much worse. Like, they don't remember anything like this. One of my senior colleagues, it's almost like she's surprised every time. I can't believe this kid came in here. Look at this growth chart. And I walk in the office, and it's a kid growing at the 40th percentile with parents who are the 40th percentile.

Scott Brown

40th percentile, meaning 40% of the rest of the country is shorter than they are, so just below average.

Short Throat

And she's like, can you believe they're here for growth? And I'm like, yes, I can believe that because-- this is, like, everyday you call me in and are flabbergasted by the same thing.

I had a conversation where I had a patient come see me. Her son was 5 foot, 7". Mom was 5' 4". Dad was 5' 8". They wanted treatment. If you say something to them like, well, his predicted height is 5' 9", you might get a response that's something like, well, that's unacceptable.

Scott Brown

[LAUGHS]

Short Throat

You're laughing, but that's my job.

Scott Brown

I'm laughing for so many different reasons.

Short Throat

Do you get it now?

Scott Brown

Oh, I get it. I've gotten it my whole life. This is probably the point in the story where I should level with you, if I could-- short joke! I'm just under 5' 3", which puts me right around the first percentile of American males by height, shorter than 99% of the men in this country. For years, I thought I was 5' 4"-- the second percentile. But a recent doctor visit confirmed that I'd been rounding up.

I've always been the smallest guy in the room, consistently smaller than other kids, for as long as I can remember. There are some downsides, sure. But I think I have a pretty good life. My successes and failures-- I do not leave them at the tiny feet of my shortness. My height is just one thing about me, not the thing, not the defining thing.

But recently, I wrote a young adult novel about a 16-year-old boy who's 4 foot 11" and struggling with his identity. And I found myself thinking every day about being short-- what it meant to me, what it might have meant, what I might have missed. And then I hear from this doctor about all of these parents who think having a son my size is unacceptable and come to her to fix it, to fix them.

Short Throat tells the families who just want to enhance their kid's height that she won't do that, but that doesn't always stop them.

Short Throat

There are some private practice pediatric endocrinologists in our area who-- the phrase I've used is I feel like they would give growth hormone to a rock if you asked them to-- like, sitting people down and giving them the worst-case scenario height prediction, and then being, like, this is what you need, and then treating them.

Scott Brown

Oh, so their consult is part of saying, you don't want this short kid here. You know?

Short Throat

Yeah.

Scott Brown

You don't want a hobbit.

Short Throat

Oh, absolutely. That's what the paren-- I know the prescribing practices of all of others peds endos in our area. Because people bounce around, and they doctor shop, and they want other opinions.

Scott Brown

Among the things that bother her the most, a lot of the parents seem oblivious to the possibility of side effects. But really, the biggest bee in Short Throat's growth hormone bonnet is the fairness aspect. The full treatment over four or five years can cost $300,000 or more.

And even though most of these families are rich, they find ways to get it covered by insurance when some of her diabetic patients can't even get the latest insulin pump covered. She also says she's seen rich families take advantage of patient assistance programs the drug companies offer to needier folks.

Short Throat

I've seen affluent patients get on these, quote, unquote, "patient assistance programs" when-- OK, this is terrible-- but sometimes I will Zillow their house. And I'll be like, you live in a $6 million home, and you're getting patient assistance for your kid's growth hormone. Gross, gross, just gross.

Scott Brown

It's important to say, Short Throat does treat some kids with growth hormone-- kids who aren't producing enough of it or any of it on their own. That's a serious health problem. But she'll also treat them if a kid is just going to be really, really short, like way, way below average, like way down in those basement percentiles where I am.

Using growth hormone is kosher in cases like this according to the FDA. That's because there's a diagnosis for people like me. I learned about it while researching my book. It's called Idiopathic Short Stature, ISS. Sounds scary, but all it means is I'm short, and no one knows why. And because I fit that diagnosis, I could have been one of Short Throat's patients.

So yes, even our whistleblower, who believes this stuff is overused, would've treated me if I'd come to her, if my parents had wanted it. And as one of those otherwise healthy kids who are just short, and who kind of resents the use of the word otherwise, I'd add, all of this looks not a whole lot like medicine. It looks cosmetic, like a boob job for kids, short kids.

But before I went off on a Napoleonic rage bender over the claims of this one rogue grow doctor, I thought I'd run those claims by Dr. David B. Allen, another pediatric endocrinologist, and arguably, the leading expert on this topic. He sat on the panel that wrote the recent guidelines for growth hormone treatments for kids. He's been writing papers about it for three decades, specifically, about idiopathic short stature.

David B. Allen

You actually-- not to get personal, but you sound like you do fit the diagnosis. You may.

Scott Brown

Did you just diagnose me over the radio?

David B. Allen

It's amazing. I've got a lot of experience.

Scott Brown

He said he didn't think unnecessary growth hormone treatments for kids was an epidemic, per se. The reluctance of insurance companies to cover such an expensive and iffy treatment keeps widespread use tamped down. But sure, there are lots of families in more image-conscious, wealthy places who put their kids on it.

When he writes about using growth hormone for height, not health, the phrase he uses is cosmetic endocrinology. And he told me this story. Back in the day, growth hormone was used almost exclusively on kids who were growth hormone-deficient, the way you give insulin to a diabetic. And the only source for this stuff back then was the pituitary glands of cadavers, dead people, so the supply was limited.

Unfortunately, because it came from cadavers, some of it was tainted with a brain disease similar to Mad Cow. It was a freak thing. This was in the '80s. Dozens of young people got sick. Some of them died. But that same year, synthetic growth hormone became available. Now there was lots of the stuff-- lab-made, safe from contamination. Dr. Allen told me and my producer, Sean Cole, that the drug industry and doctors started looking around for other uses, like, say, making idiopathically short kids less idiopathically short.

David B. Allen

Idiopathic short stature really became a thing once there was growth hormone treatment available that might work. It was a descriptive term. Of course, it's been a descriptive term for a long, long time. But as a diagnosis, I think it was more really after there was a treatment available. It's one of these situations where it's almost like a treatment that's in search of a diagnosis.

Sean Cole

So a solution in search of a problem.

David B. Allen

Sort of. Yes, right, exactly.

Scott Brown

And also, why are we treating shortness like it's a disease? Because when you look into it, as researchers have, there's no evidence tying being short to having a bad life. Studies show short kids get teased, bullied. They're often treated as younger than they are. But there's no direct connection between being small and failing at life. I, for instance, did not end up depressed and alone, living in a tiny cardboard box behind Bob's Big Boy, at least, not because of my height.

Another thing Dr. Allen said is that the use of synthetic growth hormone in kids is generally agreed to be safe. But he said, it just hasn't been on the market long enough for us to know yet. There could be an increased risk of cancer down the road. One study, and only one, points to more instances of stroke among adults who took the drug as children.

Thing is, we won't really know how dangerous this stuff is until 30, or 40, or 50 years down the line. Also, on average, kids who take growth hormone might gain three inches, a little less than half an inch per year, but that's average. Your heightage may vary a lot, could be more, could be less. I'll just note that less than a little less than 1/2 inch a year would be a very sad title for a country song.

The darkest irony here is Dr. Allen says the kids you'd think need the drug the most, kids with short parents, are the ones who benefit the least.

David B. Allen

And it's conceivable that there are some risks that we don't yet know about or are just learning about 20 years down the road, that this completely healthy 10-year-old has now been exposed to, for a benefit that we have a lot of difficulty documenting. That, to me, that's the conundrum, right?

Scott Brown

Not a conundrum for me. The health effects are unknown, benefits uncertain, and even if you get taller, you're not necessarily happier? Then I'm not putting my kid on it, not for a maximum 3 inches total, not for 1/2 inch a year. Who would choose that for their kid? I decided to find out.

Jeremy

Are you going to call this growth hormone gate? Is that what you're going to call it?

Scott Brown

That sounds snappy. We should definitely do that.

Laura

[? ?] It's funny, because--

Scott Brown

I can't tell you any of these folks' names, either. They're in Southern California. I'll call the dad Jeremy. He's a doctor. He's 5 foot 8". The mom, who I'll call Laura, is 5 foot 4". She's a personal development coach. There are two kids, Dylan and Marnie, also not their real names. Dylan's been taking growth hormone injections for five years. We asked Laura why they wanted to be anonymous.

Laura

It's a little embarrassing. Most of his, probably, peers don't know. His close friends know. But for a girl, it's cute if she's short and petite. But for a guy, it kind of says something about your masculinity. So I just wanted to protect him for whatever reasons-- short-term, long-term.

Scott Brown

They all live in a big, beautiful house with a pool that contains what I'm fairly sure is a water polo goal. Dylan's on the team. The living room is immaculate, like the lobby of a luxury hotel. When we got there, there was a dog-grooming van sitting out front in which their dog was being groomed. She looked nice afterwards.

Laura's been worrying about Dylan's size since he was a baby. He was born preemie-sized, even though she carried him full-term. He spent four or five days in the NICU. And as he got older, it just seemed like he was having a hard time catching up to his friends in the height department. He was the smallest in his team photos, class photos, always an outlier. So when she found out there was something that might help fix that, it just felt like the right call.

Laura

To me, it was just a medical choice, and it was never aesthetic. It just was more medical, and I don't know if--

Jeremy

It's interesting. We have slightly different views and perceptions.

Scott Brown

Again, this is Jeremy. He's a doctor, so you'd expect him to come at this from a medical necessity point of view, too, and he does. But he's totally upfront about his less doctor-y reasons.

Jeremy

I don't know. Stereotypical-- I'm a guy. I want him to be big and strong, if he can be bigger and stronger.

Scott Brown

But to get to that, the risk factor had to be eliminated. And so what was the point where you were like, well, now we can start thinking about bigger and stronger because I am satisfied that whatever long-term studies they are looking for--

Jeremy

There was a risk. I had to kind of take it. At least it wasn't my life, so I wasn't worried. No, I'm just kidding. Just, no.

Laura

[INAUDIBLE] punch you in this interview.

Jeremy

I'm sorry. No, it was a risk. It's not easy making that decision. Like, gosh, I'm putting my son at risk for diabetes? My brother has diabetes. I see it.

Scott Brown

Just to point out, the risk of diabetes from pediatric growth hormone use is more theoretical than anything else. Doctors monitor for it, but so far, there's no causal link.

Jeremy

So there was a little bit in the back of my mind, like, oh, boy, what did I just do to my son? Something may have happened that would have been irreversible. And so I would have just never forgiven myself had it happened. There's no question. It was in the back of my brain. I'm a doctor, so I get it.

Laura

I didn't think about it [INAUDIBLE].

Jeremy

I've worried about it in the back of my brain. I just don't verbalize it. But knock on wood, fortunately, he's been fine, and all we've seen is the benefits.

Scott Brown

Better than fine, Jeremy says. The drug seems to be working, and he's satisfied.

Jeremy

If I search my heart of hearts, at least for myself, I'd be dishonest if I said I didn't have superficial motivations exactly as you describe. Maybe not said in those words-- you know, a future leader, more attractive to a mate-- but unless you're a giant, who doesn't want to be taller?

Scott Brown

But does it feel weird to be kind of like feeding into that? Like feeding into those--

Jeremy

Stereotypes?

Scott Brown

Yeah, those societal clamoring for more.

Jeremy

No. No weirder than your trying to look nice today. Why'd you dress so nicely? You're giving into society. It looks you've got some nice shoes on. You've got a collared shirt. And when you picked your glasses, did you pick the most ugly glasses you could pick? No, you tried to pick some nice glasses, right?

Laura

[INAUDIBLE]

Jeremy

We all, to some degrees-- it's a continuum. I don't think there's anything wrong with that.

Sean Cole

But would you have been sad if he had been Scott's height?

Scott Brown

That stopped the conversation. I offered to stand up for him.

Scott Brown

This is where I stand up.

Jeremy

No, don't do that. I don't know the word sad. We would have always wondered, maybe? Like, what would have happened?

Scott Brown

But it does raise this question of, in a fully pay-to-play society, do you end up with different tiers of people, some of whom have selected characteristics that confer advantages or seem to confer advantages?

Jeremy

I get it. This smacks of the whole SAT-gate thing, right? This is all this whole, let me game the system. I want my child to get a 1600 on the SAT. I want my child to go to Harvard. It smacks of that, and I get it. But at the same time, I don't think it's all that sinister. Like, for us, we just didn't want him to be sitting below the steering wheel and being made fun of or something. That's kind of like--

Scott Brown

Which is where Jeremy and Laura's opinions about the whole thing line up a lot more. Laura used to blanch when people would ask if Dylan and his little sister were twins. She's two years younger. And Laura hated that her son wore clothes made for boys two years younger. But all of that's in the past now.

Scott Brown

Hi.

Dylan

Hi.

Scott Brown

How are you?

This is Dylan.

Dylan

Good to meet you, man.

Scott Brown

15 years old. He came home from school in the middle of the interview still wearing his school uniform-- white polo, shorts. He's 5 foot 6" now. My producer, Sean, sensitive soul that he is, had us stand back-to-back in the living room.

Sean Cole

The back of Scott's head is going right into your neck. So I wouldn't want to see you guys in an alley fight.

Scott Brown

Wow.

[LAUGHTER]

Dylan

That was hot, Sean. That was a little demeaning.

Scott Brown

Sean, I thought we were pals, buddy.

Here's the thing. Measuring yourself directly, bodily, against another human being-- it's not a natural situation. As a 43-year-old man standing back-to-back with a 15-year-old, I felt this almost primal humiliation. And just for a second, I thought, did I miss out on something? I felt a little jealous.

Laura had spread out the charts on the coffee table, inches versus years, Dylan's whole history of growing up, and up, and up from elementary school on, in a laggardly parabola that takes off like a rocket around the time he started the growth hormone. Each dot is a measurement. You know how I'm in the first height percentile for men in America? Dylan started off parked between the third and fifth percentile and ended up nearly at the 50th, almost average. It made him feel proud.

Dylan

Because I saw each dot climbing, and it was going up. It was only going up. And that, to me, was like, OK, I'm getting taller. But I'm going to be a little sad that I can't be as tall as I wanted to be. I'd like to be around 5' 10" or 5' 11", for sure. That way, I'm a little bit above average.

Scott Brown

I've never thought about it that way. What height do I want to be? How average would I like to be? This demand-side attitude about height was alien to me. And standing there, between this giant 5 foot 6" child's mastodon-like shoulder blades, I thought about what had brought me here underneath my indignation, my short identitarianism.

Here's the thing I've glossed over a bit-- the downsides of being short. I took some hard punches to the stomach in elementary school. I often feel taken less seriously by taller people in professional situations. I prefer phone meetings for that very reason. I pretty much know that I've had friendships with women that might have been more than friendships if I'd been a few inches higher off the dance floor.

I've watched the libido drain from my date's eyes as we stand up from the restaurant table after dessert. I've been judging these people, these parents, trying to check every box, buy every advantage. But there was a moment a long time ago when my parents thought about putting me on growth hormone when I was little-- littler-- and they didn't.

I have this really strong memory of their telling me they'd looked into it. We were in a car. This would have been the mid-'80s in Virginia. I remember an apple orchard on our left, a fairground on our right, and my mom telling me they'd considered it and decided against it. I remember thinking, why are you telling me this?

It's like the moment I became short, the first time I really knew. It was official. Doctors had been consulted, powerful elixirs considered. Maybe none of that should have come as a surprise. I'm the outlier amongst my siblings. My brother Robert is 6 foot 1". Even my little sister Holland is taller than I am. They take after my dad, who, at 5' 11", is a full foot taller than my mom.

In all these years, we've never talked about that decision. Why didn't they want me to get taller? Why didn't they make the choice Dylan's parents did? I went home, and I asked my mom about that conversation in the car.

Woman

See, I have no memory of this at all. How did that conversation come up? I'm driving you home from school and I go, by the way?

You know how moms have a way of making the pivotal chapters in your personal history seem less pivotal and more totally apocryphal? Yeah, it was that thing. My mom, very convincingly, debunked my big origin story of how I became short. The timeline was wrong. The location was wrong. The only true part was, once upon a time, I found out I was short. And I'm clearly more hung up on it than I thought I was.

But mom confirmed they did decide not to treat me, and we must have talked about it back then. I wanted to know why they didn't treat me. And the answer was pretty simple. When I was about 10, my pediatrician sent me to an endocrinologist to check my growth hormone levels because I was small, and doctors like to check every box.

So I got tested. I was normal, in terms of hormone levels, anyway, and that's it. They didn't pursue it further. Also, my father was a pharmaceutical researcher who tested experimental medications. My mom was a nurse. They know about this stuff. And this was right after the stories came out about the tainted growth hormone from cadavers.

Man

I had just listened to those stories. And it was kind of a gut thing. It was kind of like, well, it took them 25 years to figure that out that we had this issue. It took them 25 years. So am I going to wait 25 years to find out, oh, here's a really bad consequence of growth hormone?

Scott Brown

Of the synthetic.

Woman

Right.

Man

Of the synthetic. And we couldn't foresee it. And I had a healthy son who was thriving, I thought. And he was a sharp guy, and I didn't want to screw it up.

Scott Brown

My parents were trying to protect me by doing nothing, the same way Laura and Jeremy were trying to protect Dylan by doing something, something elemental, making him bigger.

But for my mom, there's something else. She doesn't think of what might have happened if she'd made me bigger. She thinks about what might have been lost if she had.

Woman

It's always been interesting to me to see genes will out, you know what I mean? You know, when you say, wow, you do that? And my dad did that. It's like a physical thing that somebody does, or the attitude they have, or the way they handle their hands. Those are genes coming out. That I'd like to see. They're familiar to me.

Scott Brown

They're familiar to me too. I remind myself of people I've known-- my grandfather, my uncle, my mom. I've got their bodies. I'm built on their blueprints, reliable blueprints that delivered several generations of tiny living things from primordial slime to this crazy, risky, present moment. That's no small thing. All I know is this is the box I came in, and I like it in here, I think.

Ira Glass

Scott Brown is a writer producer on the Hulu series Castle Rock. His young adult novel about a super short kid who grows freakishly tall in a year is called XL.

Coming up, when something shrinks, and shrinks, and shrinks, it can undo a 900-page law, and more about the power of tinyness. That's in a minute, from Chicago Public Radio, when our program continues.

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Today's show, "Small Things Considered," stories in defense of the little and the Lilliputian. We've arrived at Act two of our show.

Act Two: Let’s Give ‘Em Nothing to Talk About

Ira Glass

Act Two, Let's give them nothing to talk about.

David Kestenbaum has this story about something that got shrunk to exactly as small as something could possibly be shrunk with huge consequences that are playing out right now, this very moment. Here's David.

David Kestenbaum

This thing that got made small? It's a tax. A couple years ago, the government set it to zero-- 0 dollars, 0 cents-- which makes what follows so remarkable. How could a tax so small it doesn't actually exist cause any trouble? But before I explain-- and since this show is about the importance of small things-- let me just confess here how much I love zero.

It's unlike any other number in its capacity for destruction. 0 times anything is 0. No matter how big, it always wins. And even better is dividing. When I was a kid in math class, I'd like to put 1 divided by 0 into my calculator. It would show E for Error, because 1 divided by 0? There is no answer to that. It's undefined. Divide by any other number, and you're fine. 1 divided by 2, for instance, or 57, or 693.

But put a zero in, and it just blows up. Mathematicians call this kind of situation a singularity, where the math is not well-behaved. In fact, it stops making sense. There are singularities inside black holes, but I never heard of a real world example outside of that until December 14 last year.

Man

A law that brought health care to millions of Americans has been struck down by a US judge. The judge has ruled it unconstitutional.

David Kestenbaum

Maybe you remember this. A judge in Texas ruled that the entire Affordable Care Act violated the US Constitution. This was big news, and it immediately got appealed. But the signature domestic policy achievement of the entire Obama presidency, the thing that right now is giving millions of Americans health insurance, that whole thing, this judge was saying, it was unconstitutional, had to go. And the thing that set all this off? A zero.

Woman

Last year, Congress reduced the penalty tax for not having health insurance to zero. The judge ruled that without--

David Kestenbaum

Let me explain how a zero could blow up an entire law. When Obamacare, the Affordable Care Act, was written almost a decade ago, it included this thing that people called the mandate, which basically said, you have to have health insurance. And if you don't, you've got to pay a fine. In 2016, the average fine paid was a little over $700.

Opponents of the health care law took issue with that part saying, the government can't just force people to buy something they may not want. All this went to the Supreme Court, which ruled it was OK because-- and this is key-- the mandate could be viewed as a tax. The government has lots of taxes. This is one of them, which felt like the end of it.

And it was, until this other thing happened that seemed unrelated. In 2017, Republicans passed their big tax cut bill. And one of the taxes in there that they cut-- this was just a sentence-- was the mandate, the fine that you have to pay if you don't have insurance. They cut it to zero. It really does seem like most lawmakers in Congress did not understand that this one little change could be the basis for getting all 900-plus pages of the ACA ruled unconstitutional.

I couldn't find any record of lawmakers even mentioning it in the floor debate or the news coverage. One person who did see that, who put together how zero could undo the whole law, was someone not in Washington at all, a guy in Wisconsin, Misha Tseytlin, who then was the state solicitor general. I found him on Facebook. His profile picture was from an Ultimate Frisbee tournament.

He politely declined to comment. But from legal filings, we know his basic argument. Tseytlin's logic was that, if the tax is zero, then there is no tax. And what you're left with in the law is this line that basically says, people shall buy health insurance. That was OK as part of a tax, like, you shall buy health insurance, or pay a penalty. But now the tax was zero, the text of the law was simply telling people to buy health insurance-- unconstitutional.

That is how a tax of zero ends up in a federal appeals court. Most of America's kind of in the courtroom, too-- 18 red states on one side, 16 blue states on the other. I reached out to someone involved in the case, Nick Bagley, professor at the University of Michigan Law School. I talked to him about the part of the case that I find so transfixing.

David Kestenbaum

Can I say the part that stood out to me?

Nick Bagley

Yeah.

David Kestenbaum

I used to work in physics. And they call it a singularity, like it's a zero in the denominator, like it creates a black hole.

Nick Bagley

Yeah. And you're putting your finger on one of--

David Kestenbaum

Bagley, to be clear, thinks the first judge got it totally wrong. He's worked on a brief filed in the appeals case, and he's been writing about it. He pointed out something I honestly had not considered.

Nick Bagley

And I've encouraged, and others have encouraged, Congress, at least the House of Representatives, to pass a bill that would set a $1 tax.

David Kestenbaum

Oh, really?

Nick Bagley

Yeah, the House could've passed a bill that made this whole lawsuit go away tomorrow. It would be the jot of a pen. And if the House passes it, and the Senate doesn't want to pass it, well, hang that around the Senate's neck in the next presidential election. Make it their albatross to carry.

David Kestenbaum

Wait, wait, wait. Hang on. That would work, right? If they just--

Nick Bagley

Oh, absolutely.

David Kestenbaum

Yeah.

Nick Bagley

Absolutely.

David Kestenbaum

This whole case goes away if they set it to $1.

Nick Bagley

Yeah, there's a bunch of different ways you can do it.

David Kestenbaum

Or a penny.

Nick Bagley

Set it to $1.

David Kestenbaum

A penny, too, right?

Nick Bagley

A penny, sure.

David Kestenbaum

But how can it matter that it's $1 or zero, like, really, really?

Nick Bagley

It can't, and it shouldn't. And again, you're putting your finger on--

David Kestenbaum

Well, I understand that legally it might, but it seems crazy, also, that it might.

Nick Bagley

Yeah. That's one of the great things about the law.

David Kestenbaum

The great things, yeah.

Nick Bagley

Well, no, no, no, what I mean what is that, if it seems crazy to you, it probably is. And if the argument is too cute by half, it probably is.

David Kestenbaum

I talked to Bagley back in July on the day that the appeals court heard the case. We listened together online. The arguments the lawyers made were all about standing, severability doctrine, the meaning of the word shall. What did Congress intend when it set the tax to zero? It did not go well for the Affordable Care Act, for Bagley's side. You could tell from the judge's questions. Bagley's exact words while we listened included things like--

Nick Bagley

Oh, Jesus.

David Kestenbaum

And--

Nick Bagley

This is really bad. This is really bad.

David Kestenbaum

And finally--

Nick Bagley

This is about as bad as you could expect from an oral argument.

Man

Thank you, your honor.

David Kestenbaum

He was truly surprised. He thought the legal argument that zero could take down the whole law was, quote, "weak to the point of frivolousness." To Randy Barnett, though, this all seems totally logical. Barnett is a professor at Georgetown Law and has been vocal on the other side. If the tax is zero, Barnett says, the mandate's unconstitutional. He doesn't think the court can strike out just that one part of the law, so the whole thing has to go.

Randy Barnett

To me, it seems quite reasonable because it's a straightforward application of severability doctrine as I understand it.

David Kestenbaum

People on the other side feel like this case is an example of weird legal reasoning being used to get to a particular conclusion. Are there other legal decisions that look that way to you?

Randy Barnett

Yeah. I would say that any decision that says that Congress has the power, under its power to regulate commerce among the several states--

David Kestenbaum

Short answer, yes, which is to say, liberals have their examples of what they see as activist judges inventing bizarre arguments, and so do conservatives, and libertarians like Barnett, and everyone else.

He told me about this case that he argued before the Supreme Court, and lost 6 to 3. The court ruled that a woman in California couldn't grow medical marijuana at her own house in her own garden to take for her own back pain because of the Interstate Commerce Clause of the Constitution.

Randy Barnett

That sounds a little crazy to me. And yet, those kinds of rulings happen all the time.

David Kestenbaum

Give me another one.

Randy Barnett

How much airtime am I going to get?

David Kestenbaum

I asked Barnett what he made of the fact that this case is how we are deciding whether millions of Americans will have health insurance, and that it all seemed to stem, in some way, from the weird power of zero.

David Kestenbaum

Does it seem odd to you that we are in this position?

Randy Barnett

Define odd. What do you mean?

David Kestenbaum

It just seems odd that somehow there would be a difference between Congress setting a tax to a penny and zero.

Randy Barnett

Whenever you have a distinction, there's going to be marginal cases in which that distinction could make a difference, and the distinction could look arbitrary. That's just the way law works. It works that way all the time. You're speeding, by the way, when you go 36 miles an hour in a 35 mile-an-hour zone. But why is 36 miles an hour-- why is that a terrible speed when 35 miles an hour is perfectly OK?

David Kestenbaum

It feels a little different somehow.

Randy Barnett

You could say that-- well, I'm not sure how to respond to that.

[LAUGHTER]

David Kestenbaum

I'm not sure how to ask it, either.

Randy Barnett

You're entitled to your feelings.

David Kestenbaum

Here are my feelings. Having big things like this decided in the courts on legal grounds that most people will never understand-- it does not seem ideal to me. The appeals court is supposed to issue its ruling any day now. It seems quite possible this thing is headed for the Supreme Court.

It's like this little tax set to zero has created a legal wormhole with red states gathered on one side, blue states on the other, a vortex of high-level legal math in the middle. I worry it's going to suck us all into some other dimension. We'll cross some event horizon from which there is no return. It'll tear our atoms apart. It'll tear us apart. Either that, or a neatly typed opinion will come out some Tuesday morning in June.

Ira Glass

David Kestenbaum is the executive editor of our show.

Act Three: What the Eye Can’t See

Ira Glass

Act 3, What the Eye Can't See.

So we end our show today with this last story of small things that are anything but small from Lilly Sullivan.

Lilly Sullivan

When I was in my early 20s, I spent a lot of my time looking at job postings online. I'd read the qualifications section-- leadership skills, self-starter, results-oriented. And then I'd look at myself-- broke, weird, shy to the point of silence-- and miss the deadline, which is when I stumbled on a story called "The Job Application." It's by this writer, Robert Walser.

The story is told in the form of a cover letter, but instead of selling himself, he just offers an honest assessment of who he is.

"Esteemed gentlemen, I am a poor, young, unemployed person. Large and difficult tasks I cannot perform, and obligations of a far-ranging sort are too strenuous for my mind. I'm not particularly clever. And first and foremost, I do not like to strain my intelligence overmuch. I'm a dreamer rather than a thinker, a zero rather than a force, dim rather than sharp. The passion to go far in the world is unknown to me."

I remember thinking, you're not supposed to tell people that stuff. He was being funny and mocking the whole song and dance. But at the same time, he wasn't making it up. He needed a job.

He ends the letter, "Well, so now you know what sort of a person I am. I am sincere and honest, and I'm aware that this signifies precious little in the world in which we live. So I shall be waiting, esteemed gentlemen. Your respectful servant, positively drowning in obedience."

I know almost nothing about this writer, but I loved him for writing this because the thing is, feeling so worthless at that age-- it was terrifying, when your brain isn't orderly and results-oriented, like an effective human's. I'd have a rough shift temping or waitressing. People can be awful when you're at the bottom. And I'd come home just dreading the rest of my life, and he got that.

I started reading more of his stuff. One of my favorites is a novel about boys in a school where they're training to be servants. He wrote, "In one thing, we pupils are all similar. We are small, small all the way down the scale to utter worthlessness. One thing I do know for certain-- in later life, I shall be a charming, utterly spherical zero."

Robert Walser-- turns out he's Swiss, born in 1878. And for a moment, it looked like he was going to be the next big thing. Kafka, who was younger than him, was a fan. When Kafka came onto the scene, one critic back then explained Kafka by saying, hey, this guy's kind of like Robert Walser. And there was this delighted absurdity to his work.

He'd poke fun at himself for being small, but there was always an edge to it. Worse than being weak, were the people deluded enough to think they're great. It's so pompous. He wasn't mean, exactly, more just entertained by their foolishness. I started to see the world that way, too. But then one day, a few years later, I was at a bookstore, and I saw a new Robert Walser book on the shelf, more of his work translated into English.

I started reading the introduction, and it had all this stuff I hadn't known before about his life. It said that Walser had spent the last third of his life in a mental hospital-- schizophrenia. He lived there for 27 years until he died. I was floored and so sad for him. This was the writer I turned to as a roadmap to remind myself that there are people out there like me, and they're fine, and he was the best of our kind of people.

It freaked me out. Like, that's what life did to him? It turns out Robert Walser had a little early success, but not much after that. Writers liked him, but his books didn't sell well. And he was predictably terrible at marketing himself. After flailing for a while, he left the art scene in Berlin and moved back home to Switzerland. And once he's there, his life starts falling apart.

He couldn't really get his books published anymore. He starts renting out single rooms, month to month, from old ladies, reduces his possessions to a single suitcase. He's unhappy, alone all the time, mentally shaky. He'd get nightmares and stay up all night pacing and muttering to himself. Eventually, he checks himself into a mental hospital. It's 1929.

He asks the staff to put him in the shared dorm because-- this breaks my heart-- he's afraid to be alone. They diagnose him with schizophrenia. He's there voluntarily at first, but later, he gets committed against his will, kicking and screaming as they force him into the car for the transfer. He spends the rest of his life in a sanitarium.

There's a story that, when people encouraged him to write again, he said, I'm not here to write. I'm here to be mad. And the world forgot about him, and then he died, on Christmas Day, actually, in 1956. He goes for a walk outside of his asylum, and he collapses. A couple kids find his body in a field of snow. Someone actually took a photo. Robert Walser is lying face up, one arm outstretched, dark clothes against white snow, his hat a few feet away.

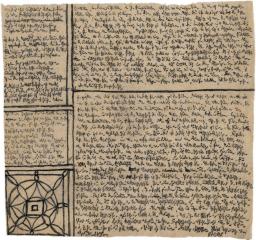

The book I was looking at had something else, something eerie. I didn't know what to make of it. After Walser died, a nurse in one of his hospitals came forward with these strange scraps of paper. His sister had a shoebox full of them too-- hundreds of little scraps, used postcards, business cards, old calendar pages ripped in half. And those little shreds were just covered in ant-like pencil markings, dense little rows of tiny slashes and ticks, packed onto shreds of paper. Everyone thinks it's just mad-man scrawl, and they put the papers away.

A few months later, his friend, who, for years, was one of the only people who really visited him in the hospital, publishes a blown-up photo of one of these scraps in a Swiss literary magazine. "Undecipherable," he writes, "a product of Walser's schizophrenia." But when the magazine comes out, a grad student writes in saying, Wait, I can read this. I think those scratchings are letters.

He got the papers and spent months staring at 24 pages trying to decipher the tiny handwriting. It turned out to be an entire novel. But there were still hundreds more scraps. It wasn't until the 1980s that someone tackled the rest of them, another grad student named Bernhard Echte, 21 at the time. He'd actually been on his way to becoming a doctor. But when he discovered Robert Walser, he stopped that life in its tracks, switched to literature to spend more time with Robert Walser.

Bernhard Echte

Because I was-- normal literature, normal text, notes-- I think most of them are boring. But Robert Walser, he's melancholic. He's funny. He is writing about everything and about nothing. And I started to read him when I was 17, and I read for him almost every day since then.

Lilly Sullivan

He talked to the archive where the shreds are being kept, and they agreed to let him see them, try to decipher some more. And when he sees them for the first time, he's stunned. The writing is microscopic, each letter just a speck, about two millimeters at first, and as the years go by, they get smaller, down to 1 millimeter-- these tiny bold characters, like miniature Japanese calligraphy.

Bernhard Echte

But the really difficult fact is the density of the lines because there's no distance between the lines.

Lilly Sullivan

Right, because if the letters are a millimeter, the pencil marking must be half a millimeter.

Bernhard Echte

Yes, yes. And this is very, very difficult because the pencil is not as sharp as it should be.

Lilly Sullivan

He brought that up a few times. Like, couldn't he sharpen his pencil?

Bernhard Echte

And this is the problem because you never know what letter is there and how many. But if you can read, you can read it because you don't spell letter for letter, but you identify the form of the word.

Lilly Sullivan

You can't identify the individual letters, but somehow when you look at them all together, sometimes you can tell what it says. A word will reveal itself. He started working on it full time with a partner. They'd sit at typewriters across from each other in a little room filled with cigarette smoke, bent over these magnifying glasses called thread counters, and they'd stare at the words.

When they'd get stumped on a word, which happened constantly, they had the system where they'd rattle off gibberish and random syllables. Bernhard and the other guy would work separately on a scrap for a while, then they'd compare their guesses. If they had come to the same conclusion, they decided it was right.

The project was supposed to take four years. It ended up taking 20. Bernhard did the last six years alone. He had started when he was 21 and finished when he was 41. And when he'd finally finished, those 526 scraps turned into six volumes of work, The Microscripts, 2,000-some pages of stories, comedy, little dramas, a novel about a robber who doesn't steal much of anything.

I had pictured this writing as sad little notes to no one. But when you read it, it's like Walser's back, happily throwing stones. Like he writes, "I've no use for these graspers. Pleasure-seekers overlook life's true pleasures. They aren't serious, which makes them boring, and they can't help being bored with me, since I'm bored with them."

Some things scholars have figured out-- Walser wrote most of these scraps before the asylum, so this romantic idea of one man alone, writing his masterpieces while locked away, seems like it didn't happen that way.

And it seems like he probably wasn't schizophrenic. Bernhard has studied all the medical records. Walser's own doctor thought he was fine and should go home. Psychiatrists who study him now don't think he was schizophrenic either. He didn't really have the symptoms.

Also, that thing he's famous for saying, "I'm not here to write. I'm here to be mad"-- people who study him think he likely didn't say that, that it's a myth, and that the truth is he got trapped there for the most infuriatingly mundane reason-- medical bureaucracy. Once he lost his rights, he couldn't get them back, couldn't sign himself out.

And during the 27 years he was there, a lot happened in the world-- World War II. That circle of writers who might have known his work, people who might have remembered that he was there, had scattered. Their books were banned. They were living in exile or dying violently. Kafka's family members were killed in the Holocaust.

So some writer no one read anymore, who no one ever really knew in the first place, people had other things to worry about. One scholar told me, she thinks that, at some point, Walser probably could have gotten out of the hospital if he wanted to, but he stopped trying.

I wondered why he spent so many years writing things that even he probably couldn't read. He explained to someone, in those years when he was really depressed, when publishers didn't want his work anymore, he had bad writer's block. He describes it as a cramp in his brain. And he explains that writing this tiny hurts. So he can take the cramp in his brain and put it into his hand, instead. And once he does that, his mind is clear, and he can think again.

On a page of a calendar he'd cut into pieces, he writes about why he did it all in pencil. One day, he figured out that a pen made him nervous-- all those mistakes, cross-outs, in ink.

But if he used a pencil instead and labored over this tiny writing, he explains, "This labor looked to me like a pleasure, as it were. I felt it would make me healthy. A smile of satisfaction would creep into my soul each time, like a smile of amicable self-derision. It seemed to me, the pencil let me work more dreamily, peacefully, cosily, contemplatively. I believe that the process I just described would blossom into a peculiar form of happiness."

Bernhard Echte

That his handwriting was small is in close connection with his convictions about life and what is interesting in life. He was not interested in great importance and things which are big and everybody knew about. The interesting things are the small things.

Lilly Sullivan

The idea I'd had about his life in the asylum, how he died, how awful it all seemed to me-- Bernhard doesn't see it that way. He's studied Walser his whole life, every letter and document. He even bought the house where Walser once lived, and he lives there now. He knows his life inside and out, and he thinks it's not tragic.

He says, Walser usually seems kind of OK. Not happy, exactly, but content. "Life without success," Walser once wrote, "can also be beautiful." His was. There's power in being OK with being nothing. It's honest. And you can't crush nothing. He made his life smaller and smaller until he almost didn't exist anymore, and then he didn't, an utterly spherical zero.

Ira Glass

Lilly Sullivan is one of the producers of our show. Other details about Walser's life and work in her story came from Susan Bernofsky. Thanks to Susan Bernofsky. She has translated eight of his books, and has just written the first-ever English biography of Walser full of the new information she's uncovered. It'll come out in about a year from Yale University Press.

Credits

Bernhard Echte

Normal literature, normal texts, notes-- I think most of them are boring.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.