744: Essential

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue: Prologue

Chana Joffe-Walt

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Chana Joffe-Walt, sitting in for Ira Glass. I've been talking to people lately about their jobs. Something is going on with jobs right now. People are leaving them, they want to leave them, where we do our jobs is changing, what we do. And I've been especially interested in people who are designated essential workers. I think for the stay at home types, people like me, our jobs changed in very obvious ways. But for people who continued to go to work in person, their jobs changed too, but those changes were sometimes less visible.

For example, Kerry Breen. He's a carpenter, works for the New York City Department of Education fixing things in schools. Spring last year when all the schools shut down for COVID, Kerry wasn't sure what that meant for him until he heard no, no, no, he should still come in, report to work.

Kerry Breen

Well, the fact that they deemed us essential I kind of found it a little comical in the beginning. That door has creaked for years, that floor has creaked for years. All of a sudden, today it's an emergency, or it's essential.

Chana Joffe-Walt

It's not like he was a doctor or a grocery store worker.

Kerry Breen

Most of our work is repairing floors, doors, ceilings that are down, bathrooms falling apart.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Do you have a favorite sort of task? Like on Monday morning if you get assigned doors are you like, ugh, more doors? Or is there one that you really like?

Kerry Breen

I wouldn't say there's a favorite. My favorite is when the building has an elevator. Because you'll get doors on the fifth floor of a building, and you've got to carry doors that weigh potentially a couple of pounds up and then back down.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Kerry is practical in this way. Kerry has been a carpenter for 35 years. He's also a volunteer firefighter, Irish, talks about his kids a lot. So he's going to work, and they're getting a lot done, because there's no kids around.

Kerry Breen

With the COVID, schools empty, things were getting painted, things were getting fixed. I've never seen the schools look so good.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And then April, a couple of weeks after the schools closed, Kerry goes in for his team meeting where they tell everyone what they're working on next.

Kerry Breen

It was I believe a Thursday or Friday afternoon. My boss said, we've got a project coming up next week, and we're going to start to build coffins.

Chana Joffe-Walt

He repeated it. We'll be building coffins for the city of New York.

Kerry Breen

Nobody in the shop believed it. We're like, get out of here. Build coffins. And he produced a set of plans and showed them to us. And he said, we're going to start next week.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Monday morning, Kerry goes to work.

Kerry Breen

And we had to go to a high school into a gymnasium that was set up as a rudimentary shop with--

Chana Joffe-Walt

A high school gymnasium with like, basketball lines on the floor kind of thing?

Kerry Breen

Yes, yes. We all get up there, and there was actually a prototype of what we had to build standing--

Chana Joffe-Walt

It was an example coffin.

Kerry Breen

Yes, I actually have a picture.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Oh. Whoa. They showed you that prototype?

Kerry Breen

Yes.

Chana Joffe-Walt

It's a simple box, standing on its end where a person's feet would be. And it's open. The cover isn't attached yet, it's just leaning against the box. In the background, you can see a scoreboard, a basketball net, and a championship banner.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And it was a basic plywood and 2 by 4 box. I've built some strange things over the years, but I've never built a coffin in my life.

Very quickly, the gym became a workshop. They set up cut stations and assembly stations. Electricians came in to install ventilation fans for all the sawdust. And about 10 carpenters got to work.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And we started bringing drafts of plywood, which is 50 sheets at a time. And we had six drafts of plywood and two drafts of 2 by 4s. And they didn't give us an end. But we were just told, this is your job for now. So we started, and we ran through all the material, got more material. Ran through that, got more material. Like, oh my god, they really need this many made?

I asked Kerry, did they know where the coffins were going? No. Did the carpenters talk about what the boxes were for? No. We just kept working.

Kerry Breen

We would get up to about 150. And so we had a very large stack of them-- it was almost a wall-- across the gym, from one end to the other.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Where do you put 150 coffins in a high school gym?

Kerry Breen

Straight across the basketball court, from one end to the other. So--

Chana Joffe-Walt

Like stacked on top of each other?

Kerry Breen

Yes, we'd stack them about five or six high. Until we got pallets, and then we placed 10 on a pallet, shrink wrap them, and I would take a forklift and back them into the elevator. I'd drive them out onto the street and up the street, through the schoolyard, down the next street, and to the back of a tractor trailer. And getting honked at for a forklift that goes too slow.

Chana Joffe-Walt

They're honking at you while you were driving the coffins?

Kerry Breen

Yes. Yes. And in three weeks of doing it, not one person in the neighborhood ever asked the question, what are those, or what are you doing?

Chana Joffe-Walt

Were you waiting for somebody to ask you?

Kerry Breen

I found it bizarre that nobody asked. Maybe nobody made the connection, or maybe nobody wanted to make the connection. It just seemed like people were going about their lives, until the final load where one guy who spoke Spanish only walks past me, and he just says, "morte," and makes sort of a slicing motion across his neck. And I just said, "si." And he shook his head and just walked away.

Chana Joffe-Walt

In the end, Kerry's team built 415 coffins. There were carpenters in other schools too. All together, they built 1,400. As I've been talking to people about their jobs, people in lots of different jobs that were deemed essential over these last 17 months, I will very regularly find myself saying something like this.

Chana Joffe-Walt

I had no idea that happened.

Kerry Breen

Well, you wouldn't.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Yeah. Do people--

Kerry Breen

Nobody did.

Chana Joffe-Walt

--know that that happened?

Kerry Breen

It was not for public knowledge. I think nobody knew how to handle it. I'm sure the schools didn't want like, hey, we're building coffins over here. It's not something you want to highlight. But now that things are waning and-- all right, you can kind of let that out.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Yeah. There's this sort of-- part of what's weird about what just happened is that there were people who had to do things that just normally are never asked of in your job. And it wasn't a war. But if it was a war, and after a war--

Kerry Breen

Yeah, yeah. It's logistics.

Chana Joffe-Walt

--you go over what happened. Yeah.

Kerry Breen

Exactly. This is how many people died. This is how many planes we built or trucks we-- whatever.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Or the fact that somebody built coffins in a high school gym in the Bronx.

Kerry Breen

Yeah. There's going to be an accounting. And it'll be the weird stats that come out of somewhere. And this is one of the stranger ones.

Chana Joffe-Walt

415 coffins. Mark it down. That happened. A year and a half ago, we asked more than 50 million Americans to continue going to work, because they had essential jobs. And they did. Nurses and doctors and also mail carriers and waitresses and construction workers, child care workers, garbage collectors all worked through this once in a century emergency.

And now, we're kind of used to it. We're focused on what's next. But do we even know what just happened? I remember calling to check in on someone early in the pandemic. She works in customs at the airport, and she told me they hadn't gotten any PPE yet, and they were nervous. They all sat right next to each other in desks in this office. So they took cardboard boxes and put them up between their desks. And then they cut holes in the boxes, so they could talk to each other.

I had the same feeling hearing that as I did with the coffins. Do people know that happened? Shouldn't we be marking that in some way? 415 coffins, that happened. And 22 jerry-rigged cardboard partitions in JFK airport, that happened too.

Today's show, I'd like to attempt to do a kind of accounting, not of how many people died or how many are unemployed, but a different kind of national accounting of all the smaller private moments that unfolded in people's jobs all across the country-- Maine, Arizona, Michigan, New York City, specifically, essential workers. We're going to hear the stories only they know, moments that changed the way people thought about their jobs, changed the choices they'll make next, and will affect the economy in ways we are only just beginning to see. That's today's show. Stay with us.

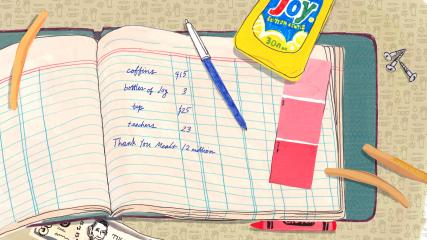

Because today's show is a kind of audit, each act name will include a number. So our first number for our ledger here is the number 3.

Act One: Three Bottles of Joy

Chana Joffe-Walt

This act is called "Three Bottles of Joy." That'll make sense in a second. So here's a small thing you would have no way of knowing what's happening underground during the pandemic. Station agents in New York City's subway system, the people who sit in booths and sell you tickets or give you directions, they were still going to work every day.

But most of the public stopped riding the trains, so it got really quiet down there. And as the weeks went on, station agents began bringing items from home into their booths to sit with them during the day-- bibles, spiritual aphorisms.

Moneta Lewis

Little stuff like that, putting mirrors. Look at you smile.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Moneta Lewis.

Moneta Lewis

We don't get a lot of that.

Chana Joffe-Walt

She's a station agent for the MTA--

Moneta Lewis

From management, we don't get a lot of that.

Chana Joffe-Walt

--New York City transit. She saw workers bringing in all sorts of things into their booths.

Moneta Lewis

At one point, we was buying the bottles of Joy. Sometimes we would have them sitting up, Joy.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Joy, like the dishwashing soap?

Moneta Lewis

Yeah. So if you see the word joy, you look at, it's going to make you smile.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Moneta says, we needed that. Made us feel less alone.

Over time, the bottles of Joy, they started to be a marker for Moneta of how their work was changing. Moneta's job is to be lunch relief for other station agents. That means she travels to a station, the agent on duty goes on lunch, and Moneta sits in their booth for 30 minutes, then travels to the next station. So she sees the inside of a lot of booths. And Moneta's an observer. Black woman, cat-eye glasses. She can talk to anyone, and she does.

She goes from South Ferry station to Rector to Chambers. She gets a bagel from the corner store at 10:30 AM. She eats it for six minutes by the window as she narrates the traffic at the four-way intersection outside. With an eye on the unmarked cop car that is always parked there waiting, she says, four or five tickets daily.

Moneta Lewis

And people cut the light, because you could cut the light four ways here. Every day.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Then it's underground. Moneta waves me into the subway through the gate. Come on, you're with the MTA lady.

Moneta Lewis

You're with me. You're with the MTA lady.

Chana Joffe-Walt

March 2020, when the pandemic shut down New York City, Moneta brought word of the virus from booth to booth. At one booth, the agent would say, do you think we should be wearing masks? And at the next booth, oh, I heard we're not supposed to. Management doesn't want us scaring the customers. Another booth, what customers? Moneta says all the agents at every booth were talking about the disappearing customers.

Moneta Lewis

Absolutely. We was, like they get to stay home? We wanted them to close the station down too. But as station agents, we had to be here on set. Yeah, so we felt a little cheated. We felt like, OK, what about us? So what are y'all going to-- We grateful to have a job, don't get me wrong. I have acquired quite a lot, even just meeting people and learning. But it was just like an uneasiness. It was like we was coming to work to get sick.

Chana Joffe-Walt

You felt like you were coming to work to get sick?

Moneta Lewis

Yes.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And they did. Transit workers began to get sick in large numbers. And they began to die in large numbers-- first a subway conductor and a bus driver, then a track worker. The MTA suffered more COVID deaths than any other agency in New York City, 171 deaths. COVID was surging, and New York City was the epicenter. It was like a plague struck this one specific agency.

A bus driver I spoke with told me, when you lose someone in the transit system, you notice. Because what transit is is a time schedule. That train pulls out at 4:31 every day. That bus passes with the same bus driver at 8:22 every morning. That person buys chips from the same vending machine in the break room at exactly 5:12. When someone dies, their absence is immediately visible.

Moneta told me she felt like suddenly work was a battle and she was a soldier trying to stay alive. A lot of transit workers felt this way. But they are not soldiers. So I would ask people, how do you make that switch? How does a person go from driving a train every day to going into work thinking you might die doing this job?

Christopher Gonsalves

The week that COVID hit my line and my terminal, I was on vacation.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Christopher Gonsalves drives the number 7 train. He's a conductor, suddenly an essential conductor, which he spoke about like he was being conscripted into an army just as the war was heating up.

Christopher Gonsalves

I just kept looking at my text messages and Facebook. Everybody at work was getting sick. And I said, wow. And I started getting worried when it was time to go back to work. I didn't want to go back. I was just thinking about it. I called my mom a lot. And I told her, I said, Ma, guess what? The week I took off, everyone got sick. And she was over here thanking the Lord. I was like, OK, Ma, I got it. Thank you, appreciate it. But I still got to go to work tomorrow.

And she's giving me the whole thing-- please be careful, wear your mask, stay far away from everybody. I said, yes, I know. And She's. Also getting on me for my vitamins. She said the vitamins is going to help. Take the vitamins. And I said, yes, Ma, I will.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Chris said his mom told him, no, no, no, do it now while we're on the phone. And then she waited until she could hear him taking his vitamins.

Christopher Gonsalves

And I was worried. And I said, Mom. I spoke to her just to tell her you're my beneficiary. If something happens, everything is set. I have life insurance. Don't worry about it. So she was worried, and I just had to calm her down a bit.

Chana Joffe-Walt

You told her, "you're my beneficiary," that was your way of calming her down?

Christopher Gonsalves

Well, she tells it to me all the time when she flies on airplanes. Yeah. It was scary but relieving. It was very relieving when I was talking to her, because she's my mother. I just had to man up and go in the next day. I didn't want to.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Moneta told me it was around this time when you'd hear about people dying daily that station agents started bringing in the bottles of Joy dish soap into their booths.

Transit workers were essential. But they were also alone. Station agents are supposed to be the eyes and ears of the subway system. But there were so few people.

Transit took away cash purchases-- fear of transmission. So subway fares were all taken on machines. Moneta was by herself sitting in the booths, looking at all the hopeful items people brought, in the bottles of Joy, and just hanging on until we got to the other side. And now, here we are, kind of at the other side? Is there another side?

Things have definitely changed underground. They're better. But Moneta's job is not the same. The people have not returned. They're not riding the trains like before. And the cash hasn't returned either. Station agents still are not allowed to take cash purchases.

Moneta Lewis

Technically, we sit there. We're not supposed to be on our phones, not supposed to be reading anything outside of transit memos. We have no customers. So where is that-- I think it's in England-- where the soldiers just sit there, they don't move, no--

Chana Joffe-Walt

Like at the Queen's palace?

Christopher Gonsalves

Yeah.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Does it make you not want to do the job anymore?

Moneta Lewis

It makes me feel like I'm unable to fully do what I was hired to do.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Say more about that. What do you mean by that?

Moneta Lewis

One of the biggest things coming down here was the busyness. I like busy stations. The money, the camaraderie with the customers, they're going to work. I'm a people's person. And most of us were.

Chana Joffe-Walt

You don't feel like a people person anymore.

Moneta Lewis

I do feel like a people person, I just feel like people don't care. And a lot of us feel that way.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Especially because recently, the MTA has proposed eliminating her position, the position of lunch relief for station agents. The union sued, and the MTA backed down. But looking forward, without cash purchases, the job of a station agent does seem much less essential. What if Moneta survived the war only to be laid off in peacetime?

I asked her recently if the bottles of Joy are still in the booths. She said nah, people took them away. You're not allowed to bring extra stuff into the booth. You could get away with it before, when we were left alone down there.

Act Two: The $25 Tip

Chana Joffe-Walt

Act 2. Moneta's job changed pretty dramatically, in ways she did not like. But most jobs didn't actually change that much. In fact, one of the strangest aspects of working through the pandemic for a lot of people was how much did not change in their jobs. That is the case with this next story. So we're going to add another number to our list. If you picture our ledger here, we've got 415 coffins, 3 bottles of joy. I feel like the next number here should have stars drawn around it or something, sparkly pen aspirational stars, like a goals list.

The number is 25. Act 2 is called "The $25 Tip." It took Shelly Ortiz a decade in the restaurant business to work up to a $25 tip. She started when she was 15 years old, got her first job as a cashier at a Five Guys in Phoenix. And Shelly walks in bubbly, ready to go. Her nickname growing up was Smiley, and you can hear it in her voice.

Shelly Ortiz

I remember I was at orientation, and I really wanted to make friends. I remember turning to a man and being like, so what high school do you go to? And he looked at me, and he was like, I'm 35. [LAUGHTER] It was just a big realization that like, I'm the youngest person here, and it shows.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Shelly describes herself as an all-in type person. And she threw herself into restaurants, all through college, her 20s. There was Five Guys, then a French bistro, a sandwich shop, a food court. And eventually, fine dining, where she finally got her first $25 tip, which was huge. She was only making $9 an hour. Shelly picked up on the routines of each place she worked easily. She loves a routine. And she loved restaurants. Shelly got rude customers all the time, people who would say things about her body, her personality, how much she was checking on the table.

Shelly Ortiz

I remember I used to work brunches a lot. I was like, the brunch girl. And brunch made good money. But brunch clientele, it's intimidating. And I remember we were running out of forks. We were running out of forks. And I think about this all the time. I think I put some spoons on a table, a very picky brunch table. Because they were getting like something that they could potentially eat it with a spoon, but they probably should have actual roll-ups with a fork and a knife and a napkin.

And I remember I came back to collect them, because we needed them, and give them actual roll-ups. And a woman slapped my hand away and said, we need those. And I was like, I'm giving you roll-ups, actual silverware. And she looked at her friend. She was like [SIGH]. Like, this girl.

And she rolled her eyes and continued to talk to the woman. And it was just a reminder that like, I am not a human to her. I have never been a person to her. I am just someone out of her world that doesn't deserve to be treated like a human being.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Shelly got it. This too was routine. It came along with the $25 tips.

Shelly Ortiz

I mean, amongst the servers, no one would be shocked to hear that. It's very common.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And it felt worth it to you.

Shelly Ortiz

Yeah. I would just think that I got her money, I got paid. So she's just another person that I don't have to think about after this. And at the end of my shift, I'd be able to go home. I'd be able to hug my girlfriend. It became like a disassociation. Like, this is not me. This is just this person who is serving, and you're going to take home this money. Take home the money.

Chana Joffe-Walt

She honed this skill to disassociate. She could shake off whatever was thrown at her. Shelly would collect the cash from the table and move on.

The mayor of Phoenix declared a state of emergency on March 17, 2020. Shelly's restaurant closed briefly. But soon after, restaurants were declared essential services in Arizona and reopened for takeout and delivery.

But Shelly hung back. Her dad was sick, recovering from a heart attack. And her mom is a nurse who was treating patients with COVID. Shelly was too scared. She told me she didn't want to apply for unemployment, because she's Puerto Rican, and she just had a sense that that kind of thing never happened for people like her. By May, restaurants in Arizona were serving people in person, and Shelly had to go back. She was still very nervous.

Shelly Ortiz

I was double masking before it was even a thing. I bought fake glasses to protect my eyes. I would only really take off my mask to drink water, and I would only drink water in the bathroom where I was alone. That's the only time I would ever get it-- and that was long shifts. I was really scared.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Meanwhile, she still had her routines. She was doing all the things she'd done thousands of times before. Welcome the customer, explain the specials, carry the plates, deliver the drinks.

Shelly Ortiz

And I was just kind of waiting for that shitty thing to happen. I would have people ask me like, pull down your mask. I want to see how much to tip you.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Pull down your mask, I want to see how much to tip you?

Shelly Ortiz

Yes.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Whoa.

Shelly Ortiz

They would want to see how pretty I was before they tipped me.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Was that a thing that happened frequently, that people would ask you to pull down your mask?

Shelly Ortiz

Yeah. That happened probably about every week. Pull down your mask so I can make sure you're smiling. Pull down your mask so-- or like, why are we still wearing masks? Do you have to wear a mask? It was always about like, either why am I wearing one, or can I see your face?

Chana Joffe-Walt

So I can know that you're smiling?

Shelly Ortiz

Yeah. So I can know you're smiling, so I can know if you're pretty. [LAUGHS] Which is so stupid. [LAUGHS] It's like, god, who gives a fuck if I'm pretty? Can I just serve you your food?

Chana Joffe-Walt

I'm sure that wasn't the first time that customers were assessing the way that you looked. But did it feel different to have it stated so baldly?

Shelly Ortiz

Yeah. So I'm 4 foot 9. I'm very short. And I have very big breasts for my frame. It's unavoidable. I'm very small, I have big boobs. And usually, like-- I'm really cute. So it's easy to just understand that people are going to be checking me out. I would have comments before. But I think when the pandemic hit, it hit harder, because I they wanted me to risk my safety so that they could see if I was cute.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Something I heard from a lot of people I talked to about working through a pandemic, people in all sorts of jobs, they said they felt like they were in a movie, that one of the strangest parts was how much did not change. It was uncanny, the way good science fiction is uncanny. It looks like normal life, but something big is off. And the parts of the job that have not changed just make the parts that feel off stand out even more.

Shelly Ortiz

I was serving a Saturday night, and it was a really busy shift. I was outside, and I was serving this couple. And they were really needy. That wasn't very rare, especially at a restaurant like this where you're paying good money for food and drink. But at the end of the shift, the gentleman-- it was a gentleman and his wife, older gentleman and his wife. And he asked me to pull down my mask, so he could see if the bottom part of my face was as cute as the top. And I said I couldn't.

And then when I said I couldn't, he said that because he couldn't focus on my face, he was forced to focus on my breasts.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Whoa.

Shelly Ortiz

And his wife was sitting right across from him. And I looked at her for any sort of response. And she just kind of gave me a blank stare in return. He said it almost like, matter-of-factly. He was like, well, if I can't look at your face, I'm forced to look at your breasts. And it was just disgusting. It just sucked, which is like, great. Awesome. Now I'm-- I think mostly during the pandemic, my self-worth was so low. I felt really disposable, obviously being objectified all the time, because half my face was covered up.

And I tried to make it work. But I wasn't adjusting the way my coworkers were. And I felt really disposable. And I just felt like another person who was destined to get sick. And it would just be another stat.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Have you felt that way before?

Shelly Ortiz

I've never felt that way before. It was like the pandemic and risking your life and not feeling of camaraderie with your teammates anymore, because it really didn't feel like anyone was taking it as seriously as me. And then I started questioning if I'm this crazy person. And I started questioning my anxiety, and then my anxiety got worse. And the anxiety and the anger got so high. But I felt like I was not adjusting the way my coworkers adjusted. I feel like people who had to work during the pandemic adopted this disassociation, and I couldn't. I couldn't separate it.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Why couldn't she? Shelly spent so much time on this question. Why couldn't she disassociate as she'd done for years when a customer slapped her hand or yelled or talked about her body? Her coworkers were going out to karaoke after work. Her customers were out with friends and family catching up.

Shelly Ortiz

I remember one time, a woman had a comment card. And she left it for me. And it said, thanks for making things feel normal. With a smiley face. And I was livid. I was like, things are not normal. This is not normal. I'm risking my life to serve you a margarita, and it's not normal. I don't want to contribute to this fantasy that a pandemic isn't happening right now.

Chana Joffe-Walt

That's really interesting. So she was trying to give you a compliment. Like--

Shelly Ortiz

Yeah, and--

Chana Joffe-Walt

--you did a good job.

Shelly Ortiz

I understand that it was coming from a kind place. But thousands of people are dying right down the road at the hospital. And I'm here serving your margarita, because I have to. Because I have to live. And it was just such an intense moment for me of realization that like, this is what I'm here to do. I'm here to create a fantasy that things aren't as bad as they are. And they are.

Chana Joffe-Walt

What is essential about restaurants? Sure, they provide jobs, food, but so do grocery stores. This was a health crisis. Doctors, nurses-- sure, essential. But what is essential about an Asian fusion place in downtown Phoenix? All these things we suddenly started calling essential services, this wasn't some long-held, agreed-upon category. We just made all this up very recently. And even then, it was pretty random.

There was federal guidance on what services should be essential, but most states didn't follow the guidance. They either came up with their own list of essential services, or they had no guidance. So if you had a liquor store in Pennsylvania, you were not essential. But in New Jersey, you were. Construction workers, that was a controversial one in a number of states. Essential or not essential?

And then there are the ones that have a particularly local flavor, like flower shops. They were essential in Delaware. And in Arizona, golf courses, essential-- also restaurants. So Shelly's restaurant was open, and millions of restaurant workers performed their normal daily routines through a pandemic. Why? What essential service did they provide? Was this it? Restaurants were essential because they helped make things feel normal?

Once Shelly thought about her job this way-- she was to continue doing all the things she'd always done, she was essential so that other people could feel normal-- it was too much for her. The tradeoff she'd been making in her head, $25 tips in exchange for some long hours, some crap from customers, that tradeoff fell apart. She didn't want to be paid for the fantasy anymore. A few weeks later, a coworker was exposed to COVID, and Shelly walked out of the restaurant.

Shelly Ortiz

And then I never went back.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Oh, that was the end for you.

Shelly Ortiz

Yeah, yeah.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Shelly got unemployment, then picked up some film jobs, went back to school for film. She told me now she doesn't think she could ever go back to serving, even after the pandemic.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Do you feel like the actual job changed, or do you think it's that you changed? Like, has it become ugly, or was it always ugly?

Shelly Ortiz

Yeah, I think that I changed more than the job changed. There's always been a certain amount of ugly that's been in the restaurant industry, especially-- sexual harassment has always been there. Verbal harassment has always been there. But it was like seeing it for the first time with new eyes. I saw a lack of kindness and courtesy, and it was constant.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Yeah. It's almost like people put on COVID goggles. And wearing the COVID goggles, they started to see their job differently.

Shelly Ortiz

Mm-hmm. I definitely saw my job differently with my COVID goggles for sure. That is what made it really ugly for me.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Here's the image I have in my mind hearing Shelly talk about where she's at right now. I picture all the governors and mayors and council members sitting down to make their lists of essential services-- hospitals, grocery stores, restaurants, golf courses. And I picture Shelly doing the same. She's making her own list of all the things she considers essential-- her life, her health, her self-worth. And she's crossing off an item at the very bottom of her list, a $25 tip.

Coming up, quitters and the people who love them. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio when our program continues.

It's This American Life. I'm Chana Joffe-Walt, sitting in for Ira Glass. This week's show, we are talking to essential workers about what happened inside their jobs over the last year and a half, things nobody else knows. And we are marking these experiences down for posterity. So that as we move into the bright and quickly darkening future, we will do so with a shared understanding of what we have just been through.

So far, we have 415 coffins, 3 bottles of Joy, and a $25 tip. We're going to be adding more to that list. And we will see what happens when people take stock one by one and wind up making some choices they never expected to make. That's what the second half of the show is about, quitters and the people they quit on. A record number of people are quitting their jobs, and they are all quitting on Miss Jordyn Rossingol.

Act Three: Teacher Number Four

Chana Joffe-Walt

That's how it feels to her, anyway, which brings us to our next act, Teacher Number Four. Miss Jordyn's Child Development Center in northern Maine has lost 23 teachers since the pandemic began. 23. Most years, Miss Jordyn told me herself, maybe one or two teachers leave. So that's our next number for our ledger, 23. 23 disappearing teachers. Miss Jordyn says the first teacher, she left right away, March 2020. She was scared of germy kids. Then another went in April, a third in May. They left for other jobs.

And then in June, Miss Jordyn says, was teacher number 4.

Jordyn Rossingol

Shania. Ah, Shania was hands-down, the best teacher I've ever had in this program, ever. I could talk for hours about Shania.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Finding good teachers and then keeping them-- this has always been a problem in early childhood education. It's one of those areas that was already a bruise, and the pandemic came and just stomped on it until the bone was broken too. For Miss Jordan, teacher number 4, Shania Bell, that felt like the break. She can't get over it.

And she's not joking about how much time she can spend lamenting this particular loss. Shania's ideas were fresh, she tells me. Her discipline was fair. Her lesson plans were thought-out. She was reliable, she was a fun coworker.

Jordyn Rossingol

In meetings, when we'd have staff meetings, I would say, OK, your voice, I want you to have Shania voice, where they could be firm, but their voice was happy. In the morning, when you drop off your child, you want to hear, good morning, my friends.

Chana Joffe-Walt

What kind of voice were people doing?

Jordyn Rossingol

Just like, oh. Good morning. How are you doing? Let's go. Get in. Come on. Oh. I know you're crying. Let's go. Just short. We had some teachers in the past who were just short. Come on, you're a big kid. Let's go. None of that. Like, no good morning, my sweet girl. Good morning, friends.

She did this calm-down method, because toddlers, toddlers get mad. And they don't know why they're mad all the time. And they're impulsive. And they want to bite or hit or run away. And she told them to blow up a balloon. And they would put their hands over their head while taking a deep breath, and they would hold it there like a balloon over their head. And then they would slowly let the air out and they would just go, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh. And they would sit by themselves. And she made a little balloon corner, is what she called it.

And they still do it. I'll still say-- even my own daughter, Monroe. Monroe, I need you to do three balloons, please. And she'll take her three deep breaths. [INHALES] Puh, puh, puh, puh, puh. And she'll release them and they're calm. So, yeah. It's just-- she has a gift. She has a gift, just amazing. Amazing. Like, you can't teach it.

Chana Joffe-Walt

See what I mean? When Miss Jordyn conceived of her early childhood center in her hometown, babies to kindergarten, she could picture it in her mind. But she says it wasn't until Shania showed up a couple of years ago, and she got to see her in a real classroom, that's when Miss Jordyn felt like, this is going to work.

Shania told me for her, when she walked into Miss Jordyn's center, 21 years old, she was nervous in a way she had not been before. Because she felt like, this is it. This is the job I actually care about, and I don't want to mess it up. And she did love the job. But then--

Shania Bell

2020 hit, and COVID hit. And for a little while, a lot of our kiddos weren't coming to school. And I was nervous, like, are we going to have to close? Am I not going to be getting paid for a little while? I don't know. There was just a lot of uncertainty.

Chana Joffe-Walt

There was the time the owner, Miss Jordyn, asked everyone to hold off on getting paid, and their paychecks came in late. And the time Shania was pretty sure her paycheck came from Miss Jordyn's personal bank account. Shania began to feel like, wait, is there no cushion in this business? She'd never really thought about the business side of things before. But once she started to, she started to have some doubts. When a friend posted about a job at the local hardware store, Shania applied. Then she had to tell Miss Jordan.

Jordyn Rossingol

So she came in my office and shut the door. And I knew that was bad when she shut the door.

Chana Joffe-Walt

This is Miss Jordyn again.

Jordyn Rossingol

And she just started crying. And she like, I was offered a job. That was the first time I ever cried when someone gave me their notice. I just lost it. [INAUDIBLE]

Chana Joffe-Walt

You started crying?

Jordyn Rossingol

Yeah, instantly. Yeah. And she was just crying. She was like, Jordyn, I can't pay my bills. I can't afford to work here.

Chana Joffe-Walt

This is obvious, but deserves saying anyway. So many of the people we call essential workers do not make a lot of money. They're overwhelmingly low-wage workers. About half the people in this country who make less than $15 an hour work in fields we now call essential. So you can be the very best at running the grill or cleaning the office building or managing rude customers at the restaurant, you can be the star teacher, teacher number 4, Shania, and still only make an average of $11 or $12 an hour-- and no health care.

Miss Jordyn barely makes enough from tuition to cover her expenses. But she's reluctant to raise rates on families, because she knows many parents can't afford to pay. And she knows from experience that if she goes too high, families are going to pull their kids all together. When Shania talked to Miss Jordyn-- and when she talked to me-- about leaving her job, she could not bring herself to say the word quit. She told Miss Jordyn, I have to get done.

Shania Bell

I knew that she was going to try everything to pay me more. But I knew that everything she was trying to do possibly wasn't going to work out in the end, just because she really couldn't afford to do that.

Chana Joffe-Walt

And you knew that.

Shania Bell

Yeah, and I knew that. And I understood.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Miss Jordyn did do all those things. She pleaded, we'll figure something out. Just give me more time. And she tried a technique that I think is maybe only applicable in a small town. When Shania said where she was going, Miss Jordyn shook her head.

Jordyn Rossingol

I said you're going to hate it. [LAUGHS]

Chana Joffe-Walt

You told her that?

Jordyn Rossingol

I said-- yeah. I was like, I love you, and I want you to be happy, but you're going to hate it. And I know the boss and the owner of it. And I said he won't love you the way I love you. I'll tell you that. And she's like, I know. I know. And I also thought like, she's going to hate that. She's going to come back.

Chana Joffe-Walt

So Shania left, and Miss Jordyn waited for her to return. In the early child care world, there were two somewhat distinct phases of the pandemic. There was the beginning, in which child care centers lost money, even as their work became labeled essential. And then there's this moment now, where what was already a chronic problem of teacher turnover has become so much worse, because the industry can't compete.

Places like Walmart, Home Depot, FedEx, grocery store chains like Kroger kept making money over the pandemic. Amazon made record profits. Child care centers did not. So teachers are leaving for jobs at Amazon or Dunkin' Donuts or grocery stores that can pay them more and sometimes give them health benefits. A woman in Ohio who owns a child care center told me, even the amusement parks can pay better than we can right now.

When Miss Jordyn lost Shania, teacher number 4 of 23, she allowed a thought that has been sitting uncomfortably to the forefront ever since. What if I can never keep someone like Shania? What if no one ever believes this is valuable?

Jordyn Rossingol

I feel like I'm constantly trying to prove myself that what I'm doing is important. I have a college degree in education. People don't know. People don't know what we do. Like, how could it cost so much? Aren't you guys just like, coloring and eating goldfish all day with them? Like, no. No.

I make lesson plans for every single classroom, infant up to the school-age program. There's so many regulations that we have to follow. There's a schedule. There's a meal plan. There's trainings that my staff have to do. We run this like a school. The only difference is that there's no public funding for us.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Why is it that essential workers happen to be some of the lowest paid workers in the country? How could a job that is so valuable be paid so little? There are some standard explanations you will hear. Many essential jobs do not require extra credentials or a lot of education. There's a lot of available labor to do these jobs. In other words, they are low-paid because they are, quote, "low-skilled" jobs.

But also, one thing that unites this broad category of low-paid essential jobs, and almost everyone you've heard from in this show, is not the kind of work they're doing, but who is doing it-- Black people, Latino people, immigrants, women, and all the people who cover more than one of those categories. 95% of child care workers are women-- white women, like Shania and Miss Jordyn, and many women of color. Almost half of child care workers are people of color. The field is much more racially and linguistically diverse than K through 12 teachers. And the people in it make much less money.

The pandemic gave child care an official stamp of essentialness in this singular moment in history when it is more clear than it has ever been and may ever be again that schools and child care are essential to the functioning of literally everything. But Miss Jordyn's work and the people doing that work may never be valued enough for her to secure more funding or for her to get Shania back.

Miss Jordyn and Shania live in a town of 8,000 people. So when Shania left, she went all the way to a job across the street. She parks in the same spot she did when she worked at Miss Jordyn's. Miss Jordyn told me, I see her all the time.

Jordyn Rossingol

She came by like, every day after work, her first week over there. And she was like, well, it's not the same. It's definitely not the same. She's like, I didn't think I was going to have to work Saturdays, and now I have to work every Saturday all summer. And I said, weird, your old boss never made you work a Saturday. [LAUGHTER]

Chana Joffe-Walt

Oh, Jordyn.

Jordyn Rossingol

Yeah. So we'd tease each other about that and stuff. And then she's come to have lunch with me a couple of times during her lunch break. The other day, I was working on a project, and I needed paint. I went over there. She was working behind the paint counter. She mixed my paint for me.

And as I watched her mix paint, I was like, I can't believe this is what you're doing. Like, you are so talented and so gifted and-- not that mixing paint isn't important. But like, that's what you're doing? She has a gift that you can't teach. It just kills me to watch her do something that is not what her gift is and her passion.

Chana Joffe-Walt

One thing economists will say about economic moments like this, when a lot of people are quitting their jobs, they'll say, it's a good thing. High quits numbers equals optimism. People are going back to school, they're going for that dream job. People feel secure enough to look around a little for what they really want to do.

This is obviously not an example of that. This is an example of a market that does not work. This is an example of a talented person who's drawn to a job that is essential that she's not doing, because it does not pay enough.

Act Four: 12 Million Thank You Meals

Chana Joffe-Walt

Act 4. There are people who are quitting who are happy about it. There are people who are mad, confused about what they want. Of course, there's the whole range. One thing I found interesting is that for many people, there was often one moment that set things in motion for them a while back, some symbol of something just being off in their job. And then it's like, these symbols just sat next to them for months, kind of haunting them until they could not deal anymore.

They found themselves doing something they never planned to do. Sometimes that was quitting, but there were some other approaches as well. So for our last story, I want to tell you about some of those symbols and then what happened next. Our last number-- it's also our biggest number in the whole show-- 12 million. Act 4, 12 Million Thank You Meals. This one I heard about from a guy in Flint, Michigan.

Flato Alexander

My name is Flato Alexander, F-L-A-T-O.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Flato is 61 years old. He's a Black man, wakes up every morning at 4:00 AM, walks to work, McDonald's, opens the store, cooks sausage, eggs, pancakes. He's in the back on his own, sometimes for many hours. He doesn't mind. He enjoys working alone. When he's at home, Flato will spend a lot of time helping out neighbors, removing snow, cutting grass. He enjoys that too, although he did mention he's a person who sometimes has a hard time saying no.

When I asked Flato what the pandemic was like for him, that's when he started telling me about how last spring, McDonald's began offering free food, Egg McMuffins.

Flato Alexander

At first I seen the commercial. And I'm like, wow, they're fitting to give away an egg muffin meal to essential workers.

Announcer

These are the most important meals we've ever served. Through May 5th, we'll be feeding first responders and health care workers Thank You Meals for free.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Remember this? I realized watching a bunch of these commercials, I'd somehow forgotten how completely everyone threw themselves in to breathlessly praising essential workers, two words most of us had never heard used together before. All of a sudden, they were everywhere. It's like we invented this category of worker to thank them.

Announcer

We'll be proudly feeding you Thank You Meals for free. It's our honor to serve you.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Anyway, Flato saw that commercial and was like, oh, that'll be me serving you.

Flato Alexander

And I'm like, oh, Lord, we fitting to get ready to be busy. That's my first thought. And the workers came, people from hospitals, nurses. They came and got the food.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Now, I thought Flato was sharing this as a moment of pride, being part of this. But no. This moment, handing out free Thank You Meals, it was the start of something for him.

Flato Alexander

Well, to be honest with you, I didn't like it. I didn't understand it. Because we here working, and you want to make some food and give it to somebody. We couldn't go nowhere and get nothing free.

Chana Joffe-Walt

You weren't getting the free food that was for the essential workers?

Flato Alexander

Yeah, that's for the essential workers.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Weren't you guys essential workers?

Flato Alexander

Yeah. So why you don't come up with something for us to have?

Chana Joffe-Walt

McDonald's gave away 12 million Thank You Meals to frontline workers. After two weeks, they stopped, but not without putting out one more commercial.

Announcer

It was an honor to meet you, an honor to thank you, and it was our honor to serve you.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Business went back to normal, but Flato kept returning to the experience in his mind. How much did that cost? All of a sudden, they have so much money for that?

Flato Alexander

They was giving it-- giving free food away. If you got the audacity to waste millions of dollars on giving somebody some food, take some of that money and make a difference with one of us. You making a difference with other people, but you still ignoring your workers. So I didn't understand it. I guess that was probably one of their shareholders meeting to come up with that idea.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Flato talked a lot about the shareholders for McDonald's, the big corporation, and also about the franchise owner, the people who own his McDonald's and about a dozen or so other stores. He says he barely saw them during the pandemic. The higher-ups, they rarely came to the store. He'd always noticed it. But handing out the Thank You Meals for health care workers, he noticed it more.

Flato Alexander

You scratching your head like, wow. No appreciation gets shown towards us. Show some type of appreciation towards the ones that's doing some work. That's what I mean. It's not no jealous thing, it's common sense. It's like a show of unconcern.

Chana Joffe-Walt

The feeling that you're describing, did that start in the last year for you?

Flato Alexander

Yeah. Yeah. To be honest with you, you are 1,000% right. It sure has. Come to the company and say good job. You guys are doing a good job. I ain't heard that this year. Thank you all for coming to work during this time.

Chana Joffe-Walt

What would it have meant to you if you had?

Flato Alexander

It would've meant a lot. It would've been a very touching thing for somebody to let you know that they have the slightest respect for your life and your livelihood. Because not showing-- a sense of unconcern to people, it's not a good feeling. It's like having a relative that won't speak to you. It makes you sad.

Chana Joffe-Walt

I thought that was such a fitting way to describe something I'd heard from a lot of people who worked through the pandemic, a feeling that while they had no choice to come to work, the people who were making all the choices-- if they had to work, how much they'd get paid, how safe they'd be-- those people appeared completely indifferent-- callous, even, like a relative who won't speak to you. A server at a pizza restaurant in Texas, Ashley Baker, told me the owner used to come in all the time. And then he vanished.

Ashley Baker

He did. He literally stopped coming to the restaurant. He literally just went AWOL. As soon as there was news saying that COVID was in El Paso, he literally disappeared.

Chana Joffe-Walt

When he showed back up months later, they were all relieved to have someone in charge, to answer their questions.

Ashley Baker

But I do remember one thing that really struck a nerve with me was that he changed his vehicle to a Corvette. And I remember that kind of struck a nerve in me. Because I'm like, wow, you're paying us minimum wage. And you want people to come in on time and stuff, but you're over here-- you have the luxury of not coming in. And you have the ability to get a brand new car. That was the moment where things just set in.

Chana Joffe-Walt

For Flato, it was the 12 million Thank You Meals. That was the symbol for him, now glowing neon. It put all the other parts of his job in a less-acceptable light. For Ashley, it was the Corvette. For employees at a McDonald's in California, perhaps it was when they raised concerns about the lack of PPE. And they say their bosses told them to use coffee filters and doggie diapers for masks.

For a guy I met outside an Amazon warehouse, it was when he says he was fired four times for having COVID. Four times. This was a thing, apparently, at Amazon. People would tell their bosses they had COVID, or they got exposed to COVID, and then they'd get fired. Later, they would hear it was an HR mistake, and they were welcome to appeal, get their job back, but not always the weeks or sometimes months of lost wages.

And for Ashley's manager at the pizza place, a woman named Soliris Morales, the Corvette pissed her off. But the real sign for her was when the restaurant cut back her hours, and she became eligible for unemployment.

Soliris Morales

I was like, how can I be making more on unemployment than my actual job? I mean, how can it be possible that they gave us all that unemployment and we're still making like-- what's the minimum wage in Texas, $7.25? Like, how?

Chana Joffe-Walt

And what lesson did you take from that?

Soliris Morales

That your boss never cares for you. [LAUGHS] I don't know.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Yeah.

These things just sat nearby as they did their jobs, nagging-- a Corvette, being fired four times, $7.25 an hour. Flato at McDonald's, he was handing out those Thank You Meals more than a year ago. He's still mad about it. He's mad about a lot of things-- that they never got hazard pay, sick pay, paid time off, health care.

The owner-operator of Flato's McDonald's says he showed his appreciation by raising wages during the pandemic. But Flato's wage is another thing that just makes him angry. He went from $11 to $12 an hour. He wants more. But the one thing Flato talked about more than any other was the fact that the franchise owner, and the people who work with him, did not come by. And when they did, they did not appear to actually see them.

Flato Alexander

No appreciation gets shown towards us. They don't know our name when they come in the building. Seemed like they showed no concern.

Chana Joffe-Walt

That's interesting, because I feel like appreciating essential workers is the one thing that we did do. Like, most places didn't pay hazard pay or higher wages or health care. But like, there was so much thank you essential workers, we appreciate you and clapping for you, and commercials. But none of that felt like anything to you?

Flato Alexander

No. Not really. My mother always said when you come into somebody's home, you're supposed to say, hey, how you doing? You're supposed to speak.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Yeah. You didn't want an ad. You wanted your actual human boss to come and say thank you.

Flato Alexander

Yeah, get everybody together in the lobby and tell us how you feel. That would be fine. That would be fine. That would be excellent for me. It've made me happy as hell.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Ashley and Solaris at the pizza restaurant, they quit. The guy I met at the Amazon warehouse, he was being pitched on a union. A group of current and former employees are now trying to organize one at the Staten Island warehouse. And Flato did something he has never done his entire working career. Recently, when his coworkers started talking about striking, he joined. It felt like not him.

Flato Alexander

Yeah, it was new for me. It was very new. And there was so many people out. It was just-- [LAUGHS] actually, it was really nice. I mean, people was everywhere.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Did you hold a sign?

Flato Alexander

No, I didn't get a chance to. And it's just sad that we have to stand outside and yell and scream and say, yeah, we want this, we want that-- when you should be sitting down and trying to come up with a plan for this to happen for us.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Did you ever expect that you would make it to 61 years old and suddenly become a guy who goes to strikes?

Flato Alexander

Well, you only can slap a person so many times. And you only can do a person wrong so many times. Imagine you got all these jobs paying $19, $20 an hour, and some of them is giving you a $300 signing bonus. And like an idiot, I still sit here and walk to the golden arches.

Chana Joffe-Walt

Flato doesn't want to quit. The McDonald's is close to his house-- he has no transportation. He can walk to work. He likes the people he works with, some of them he's worked with for many years. And he likes the work. He doesn't want to change. He wants the job to change. He wants it to be less thankless.

So many of the industries we deemed essential now seem to be in some sort of chaos. Restaurants are open now but not for dinner, because there's not enough staff. Health care workers are quitting their jobs, election officials are bailing, and school superintendents from America's three largest school systems have all quit. And things that never really worked that great before seem to be truly breaking down. I called JetBlue the other day to change a reservation, and the recording said, the current wait time is 299 minutes. Some food chains are actually raising wages-- Chipotle, Olive Garden. McDonald's is raising wages at its corporate stores-- to a small share of actual McDonald's stores, but still. Support for labor unions is the highest it's been in years.

Every week or so lately, I see a picture online posted outside a store or restaurant announcing that no one works there anymore. Like this one scotch-taped to the door that reads, "Attention Chipotle customers. We're overworked, understaffed, and underappreciated. Almost the entire staff and management have walked out of here until further notice." Or another, "we are closed indefinitely, because Dollar General doesn't pay a living wage or treat their employees with respect." I've never seen anything like it. Each sign, it seems like a whole group of employees just spontaneously and collectively decided they were done.

But you know something happened at some point before now. Some shift started with, say, a Corvette, or with 12 million Thank You Meals. One sign posted on a McDonald's drive-through menu reads, "We are short-staffed. Please be patient with the staff that did show up. No one wants to work anymore." Or another, also from a different McDonald's, with a different perspective. It reads, "We are closed because I am quitting, and I hate this job."

People quit jobs for all sorts of reasons, and there are a lot of people debating why so many are doing it right now. So I'd like to just make sure this one possibility is on the table alongside all the others. That a good number of people worked through a life-threatening pandemic feeling unseen by the very people who are supposed to care for them, feeling, as Flato did, like they have a relative who will not speak to them.

My favorite sign is from a Wendy's in North Carolina. It reads, "We all quit. CLOSED." in capital letters. And then in the corner of the sign, someone scrawled, "Bye, Alisa" with a smiley face next to it.

[MUSIC - "WORK TO DO" BY THE ISLEY BROTHERS]

Credits

Chana Joffe-Walt

Today's show was produced by Bim Adewunmi and edited by our Executive Editor, Emanuele Berry. The people who put our show together today include Susan Burton, Aviva DeKorngeld, Tobin Low, Miki Meek, Lina Mitsitzis, Stowe Nelson, Katherine Rae Mondo, Alyssa Shipp, Laura Starcheski, Lilly Sullivan, Christopher Swetala, Matt Tierney, Nancy Updike, Chloee Weiner, and Diane Wu. Our Managing Editor is Sara Abdurrahman, Senior Editor, David Kestenbaum.

Special thanks today to Rachel Lissy, Jennifer Klein, Diana Ramirez at One Fair Wage, Kate Wells, Zoe Clark, Lea Austin and Penelope Whitney, Darrick Hamilton, Robert Williams, Anne Helen Peterson, Zoé Samudzi, Gina Ginn, Tonya Breslow, Betsey Stevenson, and all the other people who spoke to me about their essential jobs. And also thanks to the excellent reporters who have focused on them in their stories, especially Eliza Shapiro, Heather Long, and Annie Lowry.

Our website, thisamericanlife.org, where you can stream our archive of over 700 episodes for absolutely free. This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange. Thanks to my boss, Ira Glass. He has this special way of testing a microphone, always the same for the last 25 years doing the show. Puh, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh, puh.

We'll be back next week with more stories of This American Life.

[MUSIC - "WORK TO DO" BY THE ISLEY BROTHERS]